The films of Studio Ghibli: Children of war

Takahata Isao had directed a number of animated television series and a few feature films when he was brought in to the fold of the newly-formed Studio Ghibli in the mid-1980s. Ghibli had been largely formed through the efforts of producer Suzuki Toshio and director Miyazaki Hayao, a longtime collaborator of Takahata's by that point; the two men had founded their new company upon the belief that family entertainment could still be made at the utmost level of craft and care, and that popularity was no enemy to artistry. It's not hard to imagine what would drive any filmmaker to hitch his wagon to that particular star, and in short order Takahata found himself adapting Nosaka Akiyuki's 1967 autobiographical novel Grave of the Fireflies into an animated feature.

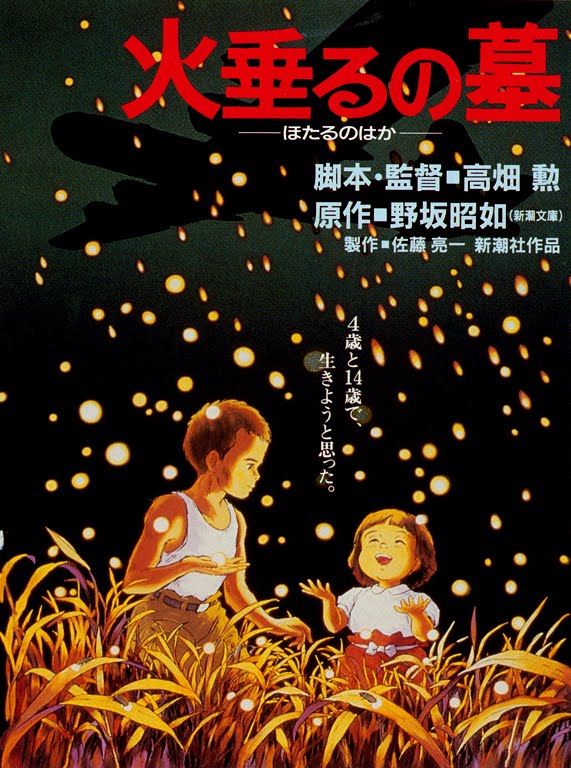

A serious tale of children suffering in a time of war, Grave was at once the tonal opposite to Ghibli's other project in development at the same time, Miyazaki's My Neighbor Totoro, and yet there was at least some solid thematic reason to link the pair: both are stories about a pair of siblings, with the older child hovering uncomfortably between childhood and adulthood, and in both cases the film commits fully to the young protagonist's POV without a whisper of condescension or smug adulthood underpinning the whole affair. They're also probably the two best animated features of the 1980s, though I don't suppose that this is something that was spoken aloud in the halls of Ghibli.

When the decision was made to release the films as a double feature, though, it had little to do with their potential affinities, and more to do with commerce: as impossible as it is to believe now, Totoro was considered a major gamble at the time, and the hope was that by pairing it with an "educational" story of Japan's contemporary history, the studio could effectively trick parents into taking their kids to see both. "Come for the lesson, stay for the woodland creatures," seems to have been the guiding principal.

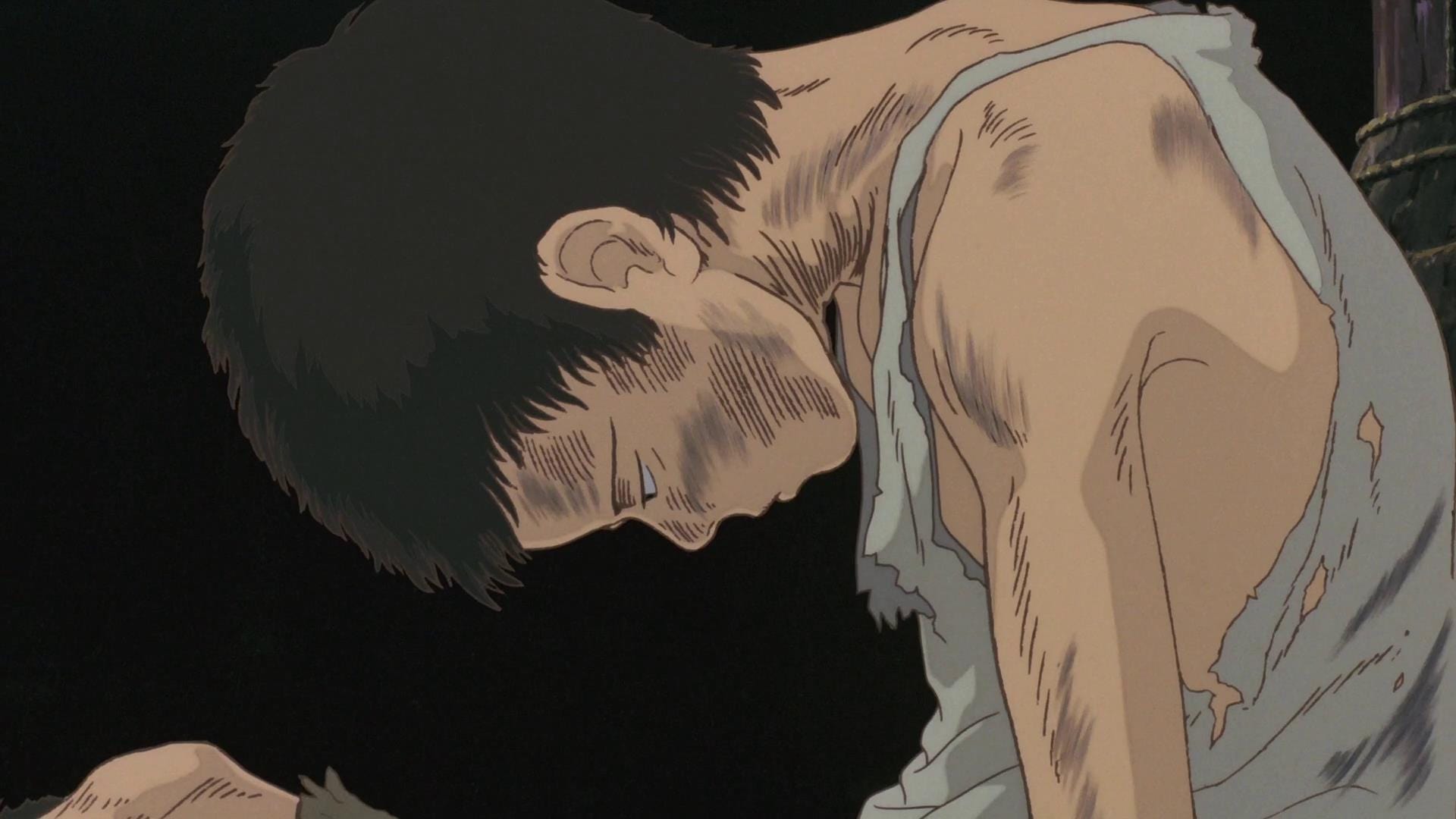

It backfired. Oddly, though the Grave/Totoro double feature was the only way to see either film in Japan upon their co-debut in April, 1988, Ghibli didn't mandate which order the films were to be screened in - meaning that half the time, this very grim war movie was given a much-welcome chaser in the form of cinema's most charming children's story, and half the time, the audience high on the adventures of the Totoros was immediately confronted with this.

You see, despite their possible points of confluence, Grave and Totoro make for a really lousy pair: the Miyazaki film is as warm and delightful as is remotely decent, while the Takahata film, while every inch a masterpiece, is... is... I'm not exactly about to spoil the film, because the first scene basically tells us what's going on. Grave of the Fireflies is ultimately a movie about watching two children starve to death in Japan in July and August, 1945.

The film opens in September of that year, as twelve-year-old Seita (Tatsumi Tsutomu) huddles in rags in a subway station. The first words we hear are his narration: "September 21, 1945. That was the night I died". And within moments, we've seen his spirit join the spirit of a six-year-old girl, who we'll shortly learn is his sister Setsuko (Shiraishi Ayano), and they are surrounded by a cloud of firefly spirits. It's a tender little scene that doesn't necessarily look like much yet, but come back to it after you've seen the rest of the movie, and it's like being hit in the gut with a jackhammer.

I wonder if it's even worth describing the plot much more, because it's stunningly simple, really: Seita and Setsuko fight through a series of miseries that would make a Charles Dickens orphan gawk and say, "whoa, y'all have it rough"; the bulk of their suffering is more or less due to the fact that Japan has well and truly lost World War II, yet the Japanese continue to act as though their victory is assured as long as they behave with obedience and honor. Meaning that a pair of kids with little money, a dead mother, and a father off God knows where on a boat haven't much chance of getting their hands on food or shelter.

I wonder if it's even worth describing the plot much more, because it's stunningly simple, really: Seita and Setsuko fight through a series of miseries that would make a Charles Dickens orphan gawk and say, "whoa, y'all have it rough"; the bulk of their suffering is more or less due to the fact that Japan has well and truly lost World War II, yet the Japanese continue to act as though their victory is assured as long as they behave with obedience and honor. Meaning that a pair of kids with little money, a dead mother, and a father off God knows where on a boat haven't much chance of getting their hands on food or shelter.

It is a film that quivers with every kind of wracking emotion: rage, sorrow, despair, fatigue, and in the end, a tiny measure of hope that perhaps there's something better than this in the next world, though even finding peace in death can't give meaning or form to something as profoundly meaningless as the death of children. The depth of human feeling expressed by the story can likely be traced ultimately back to the novelist Nosaka, who wrote his book as an attempt to apologise to the memory of his sister, who starved to death in the aftermath of the war, leading her brother to a lifetime of self-recrimination.

Wherever it came from, Takahata clearly made it his own thing; Grave of the Fireflies is not just a great and moving story, but a great and moving animated motion picture drawing upon all of the possibilities of its medium to great effect. Even at his most realistic, Miyazaki was always making "cartoons", relative to the strict realism of Grave's character design and locations.

But you could never plausibly claim that the film doesn't "need" to be animated, even if some of its greatest pleasures would still be present in a live-action version (incidentally, the book has been adapted as live-action twice since Takahata's film was produced): the way that the exact pacing of shots is carefully timed for maximum impact (there is, late in the film, a simple insert shot of rocks which Setsuko, in her childish delirium, imagines to be rice cakes: it is one of the most aggressive and profound insert shots I have ever seen); the supreme grace of Mamiya Michio's score, a haunting and sad and yearning series of cues that tell us exactly what to feel without being crude about it; even the remarkably unaffected performances by the age-appropriate child actors.

But you could never plausibly claim that the film doesn't "need" to be animated, even if some of its greatest pleasures would still be present in a live-action version (incidentally, the book has been adapted as live-action twice since Takahata's film was produced): the way that the exact pacing of shots is carefully timed for maximum impact (there is, late in the film, a simple insert shot of rocks which Setsuko, in her childish delirium, imagines to be rice cakes: it is one of the most aggressive and profound insert shots I have ever seen); the supreme grace of Mamiya Michio's score, a haunting and sad and yearning series of cues that tell us exactly what to feel without being crude about it; even the remarkably unaffected performances by the age-appropriate child actors.

You could replicate all of that in a live-action Grave of the Fireflies, but what you'd be left without in that case is the sensitivity of the animators' lines, the more-real-than-real effect of truly gifted draughtsmen sketching an everyday shape or object with only the minimum necessary detail: drawing the key lines of a thing and nothing extraneous, so that what you have onscreen is the truth of the thing, stripped to its essence. This is particularly true in Grave of the human faces we see, which are simple and straightforward, yet so expressive that you can't help but be moved.

It is, simply put, a virtually flawless animated film, beautiful at times and unspeakably horrifying at others, and never abstract. There's not a single line, image, or moment that doesn't contribute to the exhausting emotional totality of the film, both for joy (which is seldom, but when it leans towards happiness, as in the shot above, it's altogether transcendent) and for sorrow (so, so much of the film, yet for all that it's brutal, it is absolutely not an agony to sit through). It is beyond question one of the most moving movies I've ever been privileged to see, and just because what it makes you feel isn't "nice", that hardly devalues the experience of having felt it, having been shaken to your soul and reminded of what it means to be a human being, and above all to treasure life; it is a tender and fragile thing, and must be handled with care. Though it's set in a specific time and place, the film is much broader than that: it is about the senselessness of loss and war in all their forms, and if along the way it's so painful that you just about can't stand it - well, death is painful, isn't it?

It is, simply put, a virtually flawless animated film, beautiful at times and unspeakably horrifying at others, and never abstract. There's not a single line, image, or moment that doesn't contribute to the exhausting emotional totality of the film, both for joy (which is seldom, but when it leans towards happiness, as in the shot above, it's altogether transcendent) and for sorrow (so, so much of the film, yet for all that it's brutal, it is absolutely not an agony to sit through). It is beyond question one of the most moving movies I've ever been privileged to see, and just because what it makes you feel isn't "nice", that hardly devalues the experience of having felt it, having been shaken to your soul and reminded of what it means to be a human being, and above all to treasure life; it is a tender and fragile thing, and must be handled with care. Though it's set in a specific time and place, the film is much broader than that: it is about the senselessness of loss and war in all their forms, and if along the way it's so painful that you just about can't stand it - well, death is painful, isn't it?

Here is my own private response to the movie: throughout, I was terrified and heartbroken, but mostly in a very artistic sort of way. I mean to say that I was aware of feeling things because the movie led me to them, and was thus kept from fully giving myself over to it. The film ended, and I got about my business. Five minutes later, maybe a bit more, I found that I had to lie down to gather myself and have a good long cry; my legs felt like they'd give out at any second. I'll tell you this, any motion picture that can get that kind of bodily response out of me, it has to be doing something very, very right.

A serious tale of children suffering in a time of war, Grave was at once the tonal opposite to Ghibli's other project in development at the same time, Miyazaki's My Neighbor Totoro, and yet there was at least some solid thematic reason to link the pair: both are stories about a pair of siblings, with the older child hovering uncomfortably between childhood and adulthood, and in both cases the film commits fully to the young protagonist's POV without a whisper of condescension or smug adulthood underpinning the whole affair. They're also probably the two best animated features of the 1980s, though I don't suppose that this is something that was spoken aloud in the halls of Ghibli.

When the decision was made to release the films as a double feature, though, it had little to do with their potential affinities, and more to do with commerce: as impossible as it is to believe now, Totoro was considered a major gamble at the time, and the hope was that by pairing it with an "educational" story of Japan's contemporary history, the studio could effectively trick parents into taking their kids to see both. "Come for the lesson, stay for the woodland creatures," seems to have been the guiding principal.

It backfired. Oddly, though the Grave/Totoro double feature was the only way to see either film in Japan upon their co-debut in April, 1988, Ghibli didn't mandate which order the films were to be screened in - meaning that half the time, this very grim war movie was given a much-welcome chaser in the form of cinema's most charming children's story, and half the time, the audience high on the adventures of the Totoros was immediately confronted with this.

You see, despite their possible points of confluence, Grave and Totoro make for a really lousy pair: the Miyazaki film is as warm and delightful as is remotely decent, while the Takahata film, while every inch a masterpiece, is... is... I'm not exactly about to spoil the film, because the first scene basically tells us what's going on. Grave of the Fireflies is ultimately a movie about watching two children starve to death in Japan in July and August, 1945.

The film opens in September of that year, as twelve-year-old Seita (Tatsumi Tsutomu) huddles in rags in a subway station. The first words we hear are his narration: "September 21, 1945. That was the night I died". And within moments, we've seen his spirit join the spirit of a six-year-old girl, who we'll shortly learn is his sister Setsuko (Shiraishi Ayano), and they are surrounded by a cloud of firefly spirits. It's a tender little scene that doesn't necessarily look like much yet, but come back to it after you've seen the rest of the movie, and it's like being hit in the gut with a jackhammer.

I wonder if it's even worth describing the plot much more, because it's stunningly simple, really: Seita and Setsuko fight through a series of miseries that would make a Charles Dickens orphan gawk and say, "whoa, y'all have it rough"; the bulk of their suffering is more or less due to the fact that Japan has well and truly lost World War II, yet the Japanese continue to act as though their victory is assured as long as they behave with obedience and honor. Meaning that a pair of kids with little money, a dead mother, and a father off God knows where on a boat haven't much chance of getting their hands on food or shelter.

I wonder if it's even worth describing the plot much more, because it's stunningly simple, really: Seita and Setsuko fight through a series of miseries that would make a Charles Dickens orphan gawk and say, "whoa, y'all have it rough"; the bulk of their suffering is more or less due to the fact that Japan has well and truly lost World War II, yet the Japanese continue to act as though their victory is assured as long as they behave with obedience and honor. Meaning that a pair of kids with little money, a dead mother, and a father off God knows where on a boat haven't much chance of getting their hands on food or shelter.It is a film that quivers with every kind of wracking emotion: rage, sorrow, despair, fatigue, and in the end, a tiny measure of hope that perhaps there's something better than this in the next world, though even finding peace in death can't give meaning or form to something as profoundly meaningless as the death of children. The depth of human feeling expressed by the story can likely be traced ultimately back to the novelist Nosaka, who wrote his book as an attempt to apologise to the memory of his sister, who starved to death in the aftermath of the war, leading her brother to a lifetime of self-recrimination.

Wherever it came from, Takahata clearly made it his own thing; Grave of the Fireflies is not just a great and moving story, but a great and moving animated motion picture drawing upon all of the possibilities of its medium to great effect. Even at his most realistic, Miyazaki was always making "cartoons", relative to the strict realism of Grave's character design and locations.

But you could never plausibly claim that the film doesn't "need" to be animated, even if some of its greatest pleasures would still be present in a live-action version (incidentally, the book has been adapted as live-action twice since Takahata's film was produced): the way that the exact pacing of shots is carefully timed for maximum impact (there is, late in the film, a simple insert shot of rocks which Setsuko, in her childish delirium, imagines to be rice cakes: it is one of the most aggressive and profound insert shots I have ever seen); the supreme grace of Mamiya Michio's score, a haunting and sad and yearning series of cues that tell us exactly what to feel without being crude about it; even the remarkably unaffected performances by the age-appropriate child actors.

But you could never plausibly claim that the film doesn't "need" to be animated, even if some of its greatest pleasures would still be present in a live-action version (incidentally, the book has been adapted as live-action twice since Takahata's film was produced): the way that the exact pacing of shots is carefully timed for maximum impact (there is, late in the film, a simple insert shot of rocks which Setsuko, in her childish delirium, imagines to be rice cakes: it is one of the most aggressive and profound insert shots I have ever seen); the supreme grace of Mamiya Michio's score, a haunting and sad and yearning series of cues that tell us exactly what to feel without being crude about it; even the remarkably unaffected performances by the age-appropriate child actors.You could replicate all of that in a live-action Grave of the Fireflies, but what you'd be left without in that case is the sensitivity of the animators' lines, the more-real-than-real effect of truly gifted draughtsmen sketching an everyday shape or object with only the minimum necessary detail: drawing the key lines of a thing and nothing extraneous, so that what you have onscreen is the truth of the thing, stripped to its essence. This is particularly true in Grave of the human faces we see, which are simple and straightforward, yet so expressive that you can't help but be moved.

It is, simply put, a virtually flawless animated film, beautiful at times and unspeakably horrifying at others, and never abstract. There's not a single line, image, or moment that doesn't contribute to the exhausting emotional totality of the film, both for joy (which is seldom, but when it leans towards happiness, as in the shot above, it's altogether transcendent) and for sorrow (so, so much of the film, yet for all that it's brutal, it is absolutely not an agony to sit through). It is beyond question one of the most moving movies I've ever been privileged to see, and just because what it makes you feel isn't "nice", that hardly devalues the experience of having felt it, having been shaken to your soul and reminded of what it means to be a human being, and above all to treasure life; it is a tender and fragile thing, and must be handled with care. Though it's set in a specific time and place, the film is much broader than that: it is about the senselessness of loss and war in all their forms, and if along the way it's so painful that you just about can't stand it - well, death is painful, isn't it?

It is, simply put, a virtually flawless animated film, beautiful at times and unspeakably horrifying at others, and never abstract. There's not a single line, image, or moment that doesn't contribute to the exhausting emotional totality of the film, both for joy (which is seldom, but when it leans towards happiness, as in the shot above, it's altogether transcendent) and for sorrow (so, so much of the film, yet for all that it's brutal, it is absolutely not an agony to sit through). It is beyond question one of the most moving movies I've ever been privileged to see, and just because what it makes you feel isn't "nice", that hardly devalues the experience of having felt it, having been shaken to your soul and reminded of what it means to be a human being, and above all to treasure life; it is a tender and fragile thing, and must be handled with care. Though it's set in a specific time and place, the film is much broader than that: it is about the senselessness of loss and war in all their forms, and if along the way it's so painful that you just about can't stand it - well, death is painful, isn't it?Here is my own private response to the movie: throughout, I was terrified and heartbroken, but mostly in a very artistic sort of way. I mean to say that I was aware of feeling things because the movie led me to them, and was thus kept from fully giving myself over to it. The film ended, and I got about my business. Five minutes later, maybe a bit more, I found that I had to lie down to gather myself and have a good long cry; my legs felt like they'd give out at any second. I'll tell you this, any motion picture that can get that kind of bodily response out of me, it has to be doing something very, very right.