Chloe in the afternoon

For the second time this year (Shutter Island was the first), we come across a film with a twist ending that's so terrifically obvious that you almost can't help but assume the filmmakers meant for us to figure it out beforehand; and at the same time, it's rather difficult to actually discuss how the film works without reference to the twist. But I shall make a good-faith effort.

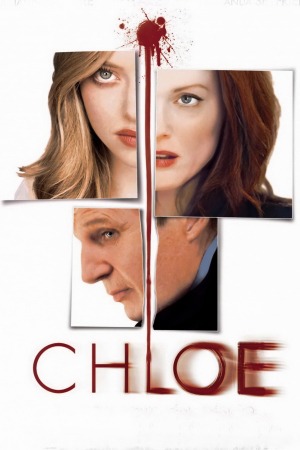

The movie in question is Chloe, the latest by Canada's Atom Egoyan, one of modern cinema's harshest psychological interrogators. A remake of Anne Fontaine's 2003 French film Nathalie (which I haven't seen), Chloe is first about the increasingly disaffected marriage of the Stewarts, Catherine (Julianne Moore) and David (Liam Neeson), and only incidentally about the titular character, a classy prostitute played by Amanda Seyfried. Briefly, the situation is thus: Catherine is certain that David is cheating on her, and after a chance encounter in the restroom of a swanky restaurant, she hires Chloe to seduce her husband and return with a full report. One report quickly turns into several reports, as Catherine finds herself both devastated by Chloe's casual news about David's infidelity, and aroused by the girl's equally casual description of the various sex acts she and the cheating man perform. Things get a lot darker than that before the thing ends; and if you've read enough reviews you've probably picked up the idea that the thing ends with a bit of a rough thud. I can't really disagree with that: it's a bit unpleasantly rushed and it takes a wildly clichéd turn that's mostly redeemed thanks to the outstanding performances by the two women. But I am getting ahead of myself.

Though it is a very sexual movie, boasting a jarringly frank sex scene that represents the exact moment that the first part of the film turns into the second part, Chloe is not at all an erotic film, nor is it meant to be; and this is what seems to have tripped up the vast majority of American critics who are so keen on pulling out the easy and tremendously inaccurate comparison between Egoyan's film and an early-'90s Skinemax late night special. Mostly, it's about Catherine's head; and the quicker the viewer realises that Chloe lied about ever meeting David, and is making up the details of their dalliances because she believes (correctly) that Catherine gets off on hearing them, the likelier the viewer is to be able to appreciate the film, and Moore's amazingly subtle exposition of a woman who refuses to acknowledge the existence of her own desires.

Erin Cressida Wilson's script (the first time Egoyan has directed a film that he didn't write) isn't necessarily subtle or nuanced about setting this up: the first time we see Catherine, she's explaining in very patient terms how the orgasm is a mechanical process (she plays a gynecologist, which may or may not have icky overtones, depending on how you read the last half-hour of the film). Nor does the rest of the film's dialogue win it any prizes for being terribly sly or clever: there's a lot of people explaining in small words exactly what they're thinking, especially in the last 20 minutes, where the film really does start to go off the rails a bit - or maybe, that's when it well and truly gets on the rails, and those rails don't lead to anywhere we want to go. It's a very tidy conclusion that the film takes for itself, and baldly expressed (there is one particular slow-motion shot, you'll know it when you see it, that is so laughably bad that it seems impossible that a gifted filmmaker like Egoyan could have been present on set the day it was filmed), and if we believe it at all, it's because Seyfried gives her all to make the character work.

Chloe is one of those movies in which a young actress tries to prove that she is a serious artist by taking off all of her clothes; it is testament to Seyfried's commitment that her eyes, and whatever secrets they mask, are always her most arresting feature. Those of us lucky enough to have spotted her in Mean Girls or the TV show Veronica Mars have known for years that she was a talent to look out for, and she's proved it in this film, where she has to play a character who necessarily doesn't exactly have a personality, and do it in a way that suggests the actual person hiding inside the persona named "Chloe" (that may or may not be her name; we never really do find out). Seyfried's role is given the brunt of the unbelievable and preposterous melodrama in the last act, and it must be confessed, that she can't absolutely save it; but she comes much closer than most 24-year-old actresses I can name would have likely done.

Both Seyfried and Moore are tasked with the unenviable job of playing two women: the version the script tells us about, and the version we only see in light of the twist. The pair of actresses are incredibly successful in this endeavor, and if Chloe only worked as a performance showcase, that would still be reason enough to justify its existence. But Egoyan is a better filmmaker than that, and despite the odd clinker of a scene here or there (one moment, in which Catherine masturbates while thinking of Chloe and David, is grossly overdetermined; but there's little besides that and the slow-motion shot that I'd call "bad"), his handling of the material is both removed and elegant. With his regular cinematographer Paul Sarossy, he frames the story as a series of boxes, and boxes-within-boxes (especially the ambitious and mostly successful motif of characters appearing in mirrors). There are many glass walls in this film, locking the characters into one version of a fish tank or another; it at once suggests the inside/outside dichotomy that is the very heart of the film's psychological investigation, while also presenting the characters as trapped, usually because of their own devices. It is thus a cruel movie; but not an unforgiving one, and though the pat ending is irritating and suggests an erotic thriller that couldn't be farther removed from Egoyan's arch visuals, it can do nothing to completely overturn the uncanny mood created by the first hour.

The movie in question is Chloe, the latest by Canada's Atom Egoyan, one of modern cinema's harshest psychological interrogators. A remake of Anne Fontaine's 2003 French film Nathalie (which I haven't seen), Chloe is first about the increasingly disaffected marriage of the Stewarts, Catherine (Julianne Moore) and David (Liam Neeson), and only incidentally about the titular character, a classy prostitute played by Amanda Seyfried. Briefly, the situation is thus: Catherine is certain that David is cheating on her, and after a chance encounter in the restroom of a swanky restaurant, she hires Chloe to seduce her husband and return with a full report. One report quickly turns into several reports, as Catherine finds herself both devastated by Chloe's casual news about David's infidelity, and aroused by the girl's equally casual description of the various sex acts she and the cheating man perform. Things get a lot darker than that before the thing ends; and if you've read enough reviews you've probably picked up the idea that the thing ends with a bit of a rough thud. I can't really disagree with that: it's a bit unpleasantly rushed and it takes a wildly clichéd turn that's mostly redeemed thanks to the outstanding performances by the two women. But I am getting ahead of myself.

Though it is a very sexual movie, boasting a jarringly frank sex scene that represents the exact moment that the first part of the film turns into the second part, Chloe is not at all an erotic film, nor is it meant to be; and this is what seems to have tripped up the vast majority of American critics who are so keen on pulling out the easy and tremendously inaccurate comparison between Egoyan's film and an early-'90s Skinemax late night special. Mostly, it's about Catherine's head; and the quicker the viewer realises that Chloe lied about ever meeting David, and is making up the details of their dalliances because she believes (correctly) that Catherine gets off on hearing them, the likelier the viewer is to be able to appreciate the film, and Moore's amazingly subtle exposition of a woman who refuses to acknowledge the existence of her own desires.

Erin Cressida Wilson's script (the first time Egoyan has directed a film that he didn't write) isn't necessarily subtle or nuanced about setting this up: the first time we see Catherine, she's explaining in very patient terms how the orgasm is a mechanical process (she plays a gynecologist, which may or may not have icky overtones, depending on how you read the last half-hour of the film). Nor does the rest of the film's dialogue win it any prizes for being terribly sly or clever: there's a lot of people explaining in small words exactly what they're thinking, especially in the last 20 minutes, where the film really does start to go off the rails a bit - or maybe, that's when it well and truly gets on the rails, and those rails don't lead to anywhere we want to go. It's a very tidy conclusion that the film takes for itself, and baldly expressed (there is one particular slow-motion shot, you'll know it when you see it, that is so laughably bad that it seems impossible that a gifted filmmaker like Egoyan could have been present on set the day it was filmed), and if we believe it at all, it's because Seyfried gives her all to make the character work.

Chloe is one of those movies in which a young actress tries to prove that she is a serious artist by taking off all of her clothes; it is testament to Seyfried's commitment that her eyes, and whatever secrets they mask, are always her most arresting feature. Those of us lucky enough to have spotted her in Mean Girls or the TV show Veronica Mars have known for years that she was a talent to look out for, and she's proved it in this film, where she has to play a character who necessarily doesn't exactly have a personality, and do it in a way that suggests the actual person hiding inside the persona named "Chloe" (that may or may not be her name; we never really do find out). Seyfried's role is given the brunt of the unbelievable and preposterous melodrama in the last act, and it must be confessed, that she can't absolutely save it; but she comes much closer than most 24-year-old actresses I can name would have likely done.

Both Seyfried and Moore are tasked with the unenviable job of playing two women: the version the script tells us about, and the version we only see in light of the twist. The pair of actresses are incredibly successful in this endeavor, and if Chloe only worked as a performance showcase, that would still be reason enough to justify its existence. But Egoyan is a better filmmaker than that, and despite the odd clinker of a scene here or there (one moment, in which Catherine masturbates while thinking of Chloe and David, is grossly overdetermined; but there's little besides that and the slow-motion shot that I'd call "bad"), his handling of the material is both removed and elegant. With his regular cinematographer Paul Sarossy, he frames the story as a series of boxes, and boxes-within-boxes (especially the ambitious and mostly successful motif of characters appearing in mirrors). There are many glass walls in this film, locking the characters into one version of a fish tank or another; it at once suggests the inside/outside dichotomy that is the very heart of the film's psychological investigation, while also presenting the characters as trapped, usually because of their own devices. It is thus a cruel movie; but not an unforgiving one, and though the pat ending is irritating and suggests an erotic thriller that couldn't be farther removed from Egoyan's arch visuals, it can do nothing to completely overturn the uncanny mood created by the first hour.