The greatest fish story ever told

At the time I write these words in the winter of 2010, Finding Nemo is the highest-grossing of all ten Pixar films, and anecdotally, the one that seems to be the closest we come to a consensus pick for their greatest work. And why not? It's arguably the most structurally sound of all their narratives, lacking the third-act drift that to one degree or another arguably plagues Toy Story 2, Monsters, Inc., WALL·E, and Cars; prior to Ratatouille, I can't really think of another Pixar film that offers so little room for a young viewer to really engage with the film - or even an adolescent viewer, for that matter. Here is a film whose primary, explicit theme is the existential terror faced by a parent when his only child, the last link to a long-since destroyed family and the center of his universe, goes missing; it is about the absolute urgency of the drive to find that lost child, an urgency trumping every other consideration or fear, and it is about the ways that this father learns more about himself and his son in the process of his search. Hell, I don't even know why I can engage with this film. But that's why the folks at Pixar are platinum-clad geniuses, and I'm just a film blogger: they could take that story and tell it in such a way that it remains the most popular of their films, one that does indeed appeal to so many children in such a profound way that its tie-in marketing campaign is second only to Cars in terms of the availability and popularity of Nemo-themed toys and clothes. I personally have a Nemo shirt, and a Nemo shot glass. I also have four different WALL·Es, so I'm not actually a very good case subject.

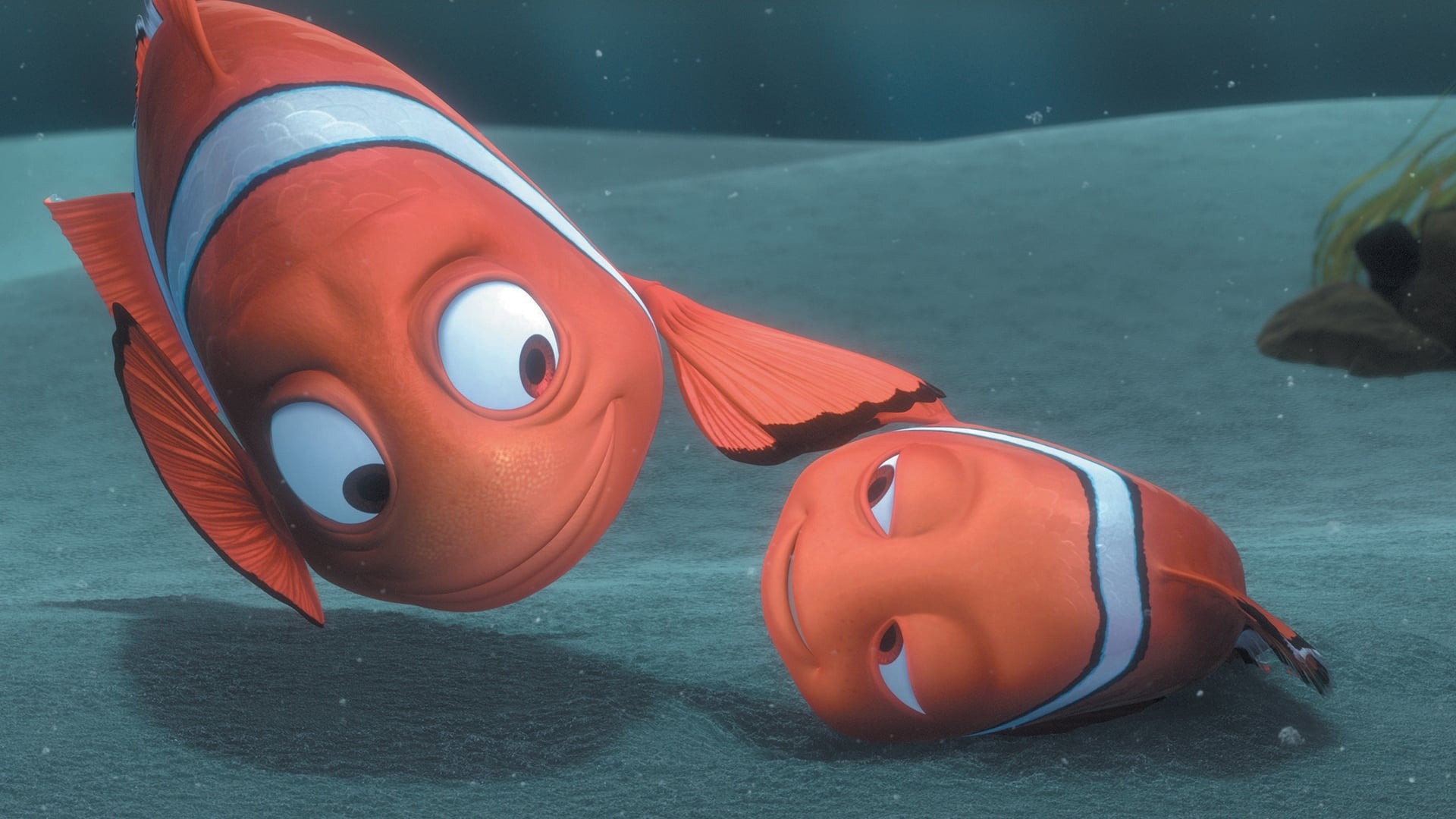

Numerous viewings have not yet revealed to me the answer to this key question of why a movie so entirely and overwhelmingly about parental angst should be so universally accessible and beloved, but I suppose the simplest answer (which is therefore likely to be the correct one) is that the film is tremendously well-made, marshaling the techniques of live-action filmmaking better than any CGI feature up to that point ever had, for the same ends that those techniques ever serve in classic Hollywood filmmaking: to invisibly but irresistibly drive the audience to the exact emotional space that the filmmakers want us to occupy. In this we have to thank Andrew Stanton, the Pixar house director with the most seemingly intuitive & effortless understanding of how cinema works, making his leading directorial debut after co-directing A Bug's Life with John Lasseter (Lee Unkrich co-directed Nemo, for the record). His potent ability to manipulate the audience is obvious from the very first moments of the film: we open on a shot of the ocean, achieved at a level of photorealistic perfection never before achieved in animation, slowly panning from the open water to a breathtakingly lovely rendering of a coral reef. Anyone with eyes who saw this on the big screen can't help but be instantly drawn in by the unmitigated visual opulence of it, and coyly noting this fact, perhaps, the first lines of the movie, spoken by Albert Brooks (one of the all-time best examples of Pixar's noted skill for casting actors that you really didn't expect to hear in a cartoon, and having it work flawlessly) are "Wow. Wow. Wow." We see two little clown fish, barely distinguishable amongst the colorful life filling the left half of the frame, as Marlin (Brooks's character) continues, "When you said you wanted an ocean view, you didn't think you were going to get the whole ocean, did you?" No, Mr. Stanton, and thank you for rising above and beyond the call.

The scene continues, establishing in swift strokes that Marlin and his wife Coral have just moved into a new neighborhood on behalf of their unborn kids - a brief wide-shot provides a nice visual gag equating the reef to any random American suburb, while giving us a decent idea of who these characters are, all of it presented in a palette of crayon-bright colors. With admirable parsimony, the two clown fish are shown to be playfully, sweetly in love with each other, and then the tone of the film shifts in a heartbeat: the score, which has been light and delicate thus far, cut out for a moment, as we see a shot from Marlin's POV that is, for the first time in the movie, almost entirely devoid of movement. Tension thus instantly developed, we cut back to a shot of Marlin, looking to the left, that slowly zooms back to reveal Coral, looking past the audience to the right. At the exact moment we cut to a shot of a large, spiny fish in the distant, the score fades back in, in a darker, minor key; we cut back to the clown fish, stunned and scared; and then to a wide shot revealing the fish (now plainly a barracuda) to be much closer than the previous shot had made it seem (a tricky bit of movement-by-editing that Stanton has cribbed from the Kurosawa playbook, and a fine playbook that is indeed). The series of shots that follow are for a brief moment still and hushed, until Coral dives for her clutch of eggs, and then the score bursts out and we're hit with a flurry of movement expressed in several shots that are far, far shorter than anything we've yet seen in the film, and Marlin is knocked into blackness with one last roar of sound. He comes too, and the bright colors have been replaced by a field of dim blues, and the score is a hesitant wall of atonal strings. Marlin descends to find his wife and all but one of their hundreds of eggs gone.

I apologise for being so anally specific about this brief scene, but it's a magnificent example of how Stanton's control over the medium gives Finding Nemo so much of its particular emotional kick. There's the mixture of pure audience-wowing spectacle with images very clearly tied to the characters' perspectives, giving us both the scope of this world and defining the personal scale of the story which will take place within it; the combination of long and short "takes" is perfectly calibrated to first ease give us a sense of the characters' languid ease of life, then the horrid stillness of that moment of dread, and finally a shot of heart-stopping terror; and most amazing of all, the abrupt cut to black that divides the two very distinct color schemes, a moment of awful possibility in which, for just a second, we can't know what happened other than an untethered feeling of death (it is, for my money, the most truly distressing scene of a parent dying in the long, parent-unfriendly annals of American feature animation). Even if we have no particular reason to feel anything about the idea of two parents moving into the nice neighborhood to raise a family, everything about the very deliberate construction of this scene gives us one and only one possible response to every beat: Stanton plays the viewer like a fiddle, and it's a privilege to be played.

And that level of control and precision is present in every scene of the film: though some Pixar films use the particular language of the camera in far more evocative ways, I don't know if any of them would reward a shot-by-shot close reading as readily as Finding Nemo.

Of course, you need only see the film to know the rest: that it has a marvelous cast of characters brought to life by an equally marvelous stable of actors, with Ellen DeGeneres in particular deserving every bit of the praise she's received over the years for her performance. The score by Thomas Newman - the first time a Pixar film had been scored by anyone other than Randy Newman, incidentally (fun fact: more different individuals have directed Pixar features than written music for Pixar features) - is a real triumph, gliding and just slightly to the side of pure tonality, evoking the quicksilver aspect of water without necessarily feeling "wet" - because, of course, to a fish, the wetness of water is its least important quality. I think I can be safe in arguing that it is less outwardly funny than any Pixar film to precede it (it may in fact retain the title of "least funny Pixar movie", though the studio has taken decisive steps away from comedy in the last five years), but there are still gags in the film that are as excellent as anything else to come out in the decade; the "mine! mine!" seagulls, of a certainty, are one of the great comic creations of the '00s.

So, what have I done here? Nothing but to say, "this movie deserves praise - continue to praise it for the reasons we all have done since 2003". I feel curiously unguilty about doing so. When a movie is as flat-out good as Finding Nemo, there's not much else that you can say; sometimes it just feels really good to love something and share that love.

Numerous viewings have not yet revealed to me the answer to this key question of why a movie so entirely and overwhelmingly about parental angst should be so universally accessible and beloved, but I suppose the simplest answer (which is therefore likely to be the correct one) is that the film is tremendously well-made, marshaling the techniques of live-action filmmaking better than any CGI feature up to that point ever had, for the same ends that those techniques ever serve in classic Hollywood filmmaking: to invisibly but irresistibly drive the audience to the exact emotional space that the filmmakers want us to occupy. In this we have to thank Andrew Stanton, the Pixar house director with the most seemingly intuitive & effortless understanding of how cinema works, making his leading directorial debut after co-directing A Bug's Life with John Lasseter (Lee Unkrich co-directed Nemo, for the record). His potent ability to manipulate the audience is obvious from the very first moments of the film: we open on a shot of the ocean, achieved at a level of photorealistic perfection never before achieved in animation, slowly panning from the open water to a breathtakingly lovely rendering of a coral reef. Anyone with eyes who saw this on the big screen can't help but be instantly drawn in by the unmitigated visual opulence of it, and coyly noting this fact, perhaps, the first lines of the movie, spoken by Albert Brooks (one of the all-time best examples of Pixar's noted skill for casting actors that you really didn't expect to hear in a cartoon, and having it work flawlessly) are "Wow. Wow. Wow." We see two little clown fish, barely distinguishable amongst the colorful life filling the left half of the frame, as Marlin (Brooks's character) continues, "When you said you wanted an ocean view, you didn't think you were going to get the whole ocean, did you?" No, Mr. Stanton, and thank you for rising above and beyond the call.

The scene continues, establishing in swift strokes that Marlin and his wife Coral have just moved into a new neighborhood on behalf of their unborn kids - a brief wide-shot provides a nice visual gag equating the reef to any random American suburb, while giving us a decent idea of who these characters are, all of it presented in a palette of crayon-bright colors. With admirable parsimony, the two clown fish are shown to be playfully, sweetly in love with each other, and then the tone of the film shifts in a heartbeat: the score, which has been light and delicate thus far, cut out for a moment, as we see a shot from Marlin's POV that is, for the first time in the movie, almost entirely devoid of movement. Tension thus instantly developed, we cut back to a shot of Marlin, looking to the left, that slowly zooms back to reveal Coral, looking past the audience to the right. At the exact moment we cut to a shot of a large, spiny fish in the distant, the score fades back in, in a darker, minor key; we cut back to the clown fish, stunned and scared; and then to a wide shot revealing the fish (now plainly a barracuda) to be much closer than the previous shot had made it seem (a tricky bit of movement-by-editing that Stanton has cribbed from the Kurosawa playbook, and a fine playbook that is indeed). The series of shots that follow are for a brief moment still and hushed, until Coral dives for her clutch of eggs, and then the score bursts out and we're hit with a flurry of movement expressed in several shots that are far, far shorter than anything we've yet seen in the film, and Marlin is knocked into blackness with one last roar of sound. He comes too, and the bright colors have been replaced by a field of dim blues, and the score is a hesitant wall of atonal strings. Marlin descends to find his wife and all but one of their hundreds of eggs gone.

I apologise for being so anally specific about this brief scene, but it's a magnificent example of how Stanton's control over the medium gives Finding Nemo so much of its particular emotional kick. There's the mixture of pure audience-wowing spectacle with images very clearly tied to the characters' perspectives, giving us both the scope of this world and defining the personal scale of the story which will take place within it; the combination of long and short "takes" is perfectly calibrated to first ease give us a sense of the characters' languid ease of life, then the horrid stillness of that moment of dread, and finally a shot of heart-stopping terror; and most amazing of all, the abrupt cut to black that divides the two very distinct color schemes, a moment of awful possibility in which, for just a second, we can't know what happened other than an untethered feeling of death (it is, for my money, the most truly distressing scene of a parent dying in the long, parent-unfriendly annals of American feature animation). Even if we have no particular reason to feel anything about the idea of two parents moving into the nice neighborhood to raise a family, everything about the very deliberate construction of this scene gives us one and only one possible response to every beat: Stanton plays the viewer like a fiddle, and it's a privilege to be played.

And that level of control and precision is present in every scene of the film: though some Pixar films use the particular language of the camera in far more evocative ways, I don't know if any of them would reward a shot-by-shot close reading as readily as Finding Nemo.

Of course, you need only see the film to know the rest: that it has a marvelous cast of characters brought to life by an equally marvelous stable of actors, with Ellen DeGeneres in particular deserving every bit of the praise she's received over the years for her performance. The score by Thomas Newman - the first time a Pixar film had been scored by anyone other than Randy Newman, incidentally (fun fact: more different individuals have directed Pixar features than written music for Pixar features) - is a real triumph, gliding and just slightly to the side of pure tonality, evoking the quicksilver aspect of water without necessarily feeling "wet" - because, of course, to a fish, the wetness of water is its least important quality. I think I can be safe in arguing that it is less outwardly funny than any Pixar film to precede it (it may in fact retain the title of "least funny Pixar movie", though the studio has taken decisive steps away from comedy in the last five years), but there are still gags in the film that are as excellent as anything else to come out in the decade; the "mine! mine!" seagulls, of a certainty, are one of the great comic creations of the '00s.

So, what have I done here? Nothing but to say, "this movie deserves praise - continue to praise it for the reasons we all have done since 2003". I feel curiously unguilty about doing so. When a movie is as flat-out good as Finding Nemo, there's not much else that you can say; sometimes it just feels really good to love something and share that love.

Categories: adventure, animation, best of the 00s, domestic dramas, pixar, sassy talking animals