Porn nations

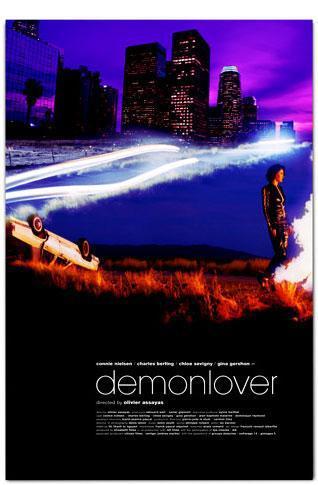

No film by the chameleon-like director Olivier Assayas met with as much brutal misunderstanding - at least, in the United States; I cannot speak to its reception in Europe - as 2002's demonlover, a stupendously intelligent assault on globalism, e-commerce, the media, corporate culture - oh, and violent pornography, although insofar as the movie has anything to say about pornography or sexuality at all, it's only as a means to the greater end of savaging life in the age of the internet (because, as much as we don't like to admit it, we all know that the internet really is for porn, and Avenue Q wasn't just making a snotty joke). To judge from most of the film's majority of negative reviews, you'd think that this porn angle was somehow enough to make demonlover some kind of half-assed erotic techno-noir thriller; but it's hard to imagine a thriller of any stripe more aggressively un-erotic than this one.

At heart, it's basically a corporate espionage mystery; not the most well-worn genre in the film industry, maybe, but familiar enough in the essentials that it's easy to hang on to what's happening. Karen (Dominique Reymond) is the chief negotiator working on behalf of a French media company, the Volf Corporation, in deals with a Japanese content provider called TokyoAnime, hentai producers just on the cusp of a bold new world in fully-rendered CGI porn cartoons. But Karen has herself some internal competition, in the form of Diane de Monx (Connie Nielsen), assistant to the company's owner Henri-Pierre Volf (Jean-Baptiste Malartre); Diane endeavors to have Karen drugged and attacked, so that the older woman is forced to step away from the deal, leaving Diane with Karen's antagonistic assistant Elise (Chloë Sevigny) and business partner Hervé (Charles Berling), and best of all, her position.

The TokyoAnime papers are inked, and Diane moves to her next, and far more lucrative prospect: the American company Demonlover.com, in the form of a negotiator named Elaine Si Gibril (Gina Gershon), wants to get at TokyoAnime through Volf, as this will give them 75% of the world hentai market and drive their hated competitors Mangatronics out of business; but this deal starts to run into trouble when Volf (the man, not the company) has strong objections to Demonlover's alleged relationship to a site called the Hellfire Club, where anyone willing to pay the money can watch women tortured in real time, with a neat-o user command interface. Needless to say, the Hellfire Club is a massively illegal operation, and if Demonlover really is connected with it, Volf will have absolutely nothing to do with it: they're perfectly okay with porn, but are terrified at anything that might get them prosecuted, as we already saw with their tentative concerns about the TokyoAnime deal.

From here on - 45 minutes into the movie - I must let the plot tend to itself, for that's as far as we can go without hitting spoilers, and while the narrative of demonlover is not at all its most important element, it wouldn't be fair to give away some of the slinkiest turns and twists it makes in a second hour that is quite amazingly dense with plot curves.

Anyway, we've got more than enough to work on: what matters more than the particular details of who's betraying who is the wholly impersonal world in which all of these deals are made, a world that is very specifically and important not presented as wicked and immoral; it is far scarier and more accurately amoral, made up of people so invested in money and trade that they have seemingly forgotten any actual real-world consequence to the sordid material in which they traffic. The closest anyone ever comes to making any sort of moral judgment one way or the other comes when the French team is visiting the TokyoAnime studio, and Hervé, watching a scene of a girl being raped by eels, cracks "It looks bad for her," a gag so lame he doesn't even let the translator explain it to the Japanese representatives, as Diane smiles absently and lights a cigarette. That is the kind of person we're looking at throughout demonlover: corporate bureaucrats so withdrawn from humanity that they aren't bothered by watching girlish cartoon figures getting raped except for their concern that the French authorities might view the characters' lack of pubic hair as a signifier that they're minors, or whose response to something as plainly evil as the Hellfire Club is to idly suggest that it's "fascinating". Though the gold standard in this regard is certainly the American Elaine's admission that the Hellfire Club is a well-made, enviable site, not without a trace of envy.

It's maybe difficult to work up moral indignation against the absence of moral consciousness, but Assayas is a director always up for a hard job, and his treatment of this milieu makes clear his absolute hatred for an international climate in which this kind of filth can be discussed solely in terms of its financial value in ways that could hardly be imagined in any other medium than the cinema. There are two visual cues in particular that dominate demonlover and propel its arguments far more readily than any amount of speaking could, not that any of the characters in the film are particularly inclined towards mouthing Assayas's arguments: the first of these is an icy-blue color palette that dominates virtually every moment of the film, washing out the characters and leaving them looking rather artificial and robotic. The actors' deliberately vacant performances help with this feeling, but it mostly comes down to the director's frequent cinematographer Denis Lenoir to blend the harsh under-lighting of film noir with this steely color scheme in a way that leaves the world of the film seeming mechanical and brutal. The other cue, and the more important I'd wager, although much more difficult to explain, is the careful positioning of the camera, which usually adopts a perspective quite separate from anyone onscreen, especially in the moments when we in the audience are watching the hentai or the Hellfire Club site: we're "between" the characters and the media, as it were, closer to the screen than any real-life viewer ever would be, so close that at times it loses definition. It's almost as though the director is rubbing our noses in the stuff that his characters barely even notice. In this regard, the grand final shot is a particular corker: inn which a victim of the Hellfire Club is staring blankly at the home viewer, who isn't even watching his screen - but we, the movie viewer, are looking straight at her, and she at us, just for a second until the camera shifts away. The implications are legion, but the one I like best is that Assayas and the character are both daring us to admit our own culpability in living in a media-soaked culture like the one in the film, a culture in which the moral value of media has been so sand-blasted away by multitasking and increasing audience savviness that we can too easily forget that there are ramifications to media consumption.

It's a nasty-minded attack on the plugged-in lifestyle that Westerners - I suspect Americans especially - have come to love so much since the mid-'90s, and I expect this has much to do with the cold reception given the film, or the odd fixation on its "narrative breakdown" after the half-way mark. It's not really a breakdown at all, though it switches gears from the easily-digested "companies suck" story of the first half; now we're confronted directly with the personal effects on the characters who live and breath in the environment that the first half defines. It's an elegant and, in hindsight, absolutely inevitable track-jumping that gives demonlover most of its truly unsettling impact, and it's not at all fun to grapple with a film that takes such nasty delight in pointing out how much human-scale damage is done by the modern world, especially given the film's whole-hearted refusal to offer any solutions or answers - like the problem of "business love unfettered capitalism" has any solutions! Now, all I've said has a single, major knock against it, which is that the precise world imagined by demonlover looks somewhat little like the internet-addled world of 2010, and it's not exactly like I remember 2002 being, either (of course, the idea of literal torture porn has only gained credibility since 2002). But there are enough discomfiting overlaps between Assayas's world and ours - the only flat-out error in representation I caught was when he showed an American teenager's room with a poster for the 1998 Godzilla - that it's doesn't take much squinting to see how the two could align; and the idea that corporations run amok are able to do incalculable damage to society and to the individuals caught up in those corporate cultures is something that sadly, is quite obvious even eight years later, even without the veil of a techno-thriller fable.

At heart, it's basically a corporate espionage mystery; not the most well-worn genre in the film industry, maybe, but familiar enough in the essentials that it's easy to hang on to what's happening. Karen (Dominique Reymond) is the chief negotiator working on behalf of a French media company, the Volf Corporation, in deals with a Japanese content provider called TokyoAnime, hentai producers just on the cusp of a bold new world in fully-rendered CGI porn cartoons. But Karen has herself some internal competition, in the form of Diane de Monx (Connie Nielsen), assistant to the company's owner Henri-Pierre Volf (Jean-Baptiste Malartre); Diane endeavors to have Karen drugged and attacked, so that the older woman is forced to step away from the deal, leaving Diane with Karen's antagonistic assistant Elise (Chloë Sevigny) and business partner Hervé (Charles Berling), and best of all, her position.

The TokyoAnime papers are inked, and Diane moves to her next, and far more lucrative prospect: the American company Demonlover.com, in the form of a negotiator named Elaine Si Gibril (Gina Gershon), wants to get at TokyoAnime through Volf, as this will give them 75% of the world hentai market and drive their hated competitors Mangatronics out of business; but this deal starts to run into trouble when Volf (the man, not the company) has strong objections to Demonlover's alleged relationship to a site called the Hellfire Club, where anyone willing to pay the money can watch women tortured in real time, with a neat-o user command interface. Needless to say, the Hellfire Club is a massively illegal operation, and if Demonlover really is connected with it, Volf will have absolutely nothing to do with it: they're perfectly okay with porn, but are terrified at anything that might get them prosecuted, as we already saw with their tentative concerns about the TokyoAnime deal.

From here on - 45 minutes into the movie - I must let the plot tend to itself, for that's as far as we can go without hitting spoilers, and while the narrative of demonlover is not at all its most important element, it wouldn't be fair to give away some of the slinkiest turns and twists it makes in a second hour that is quite amazingly dense with plot curves.

Anyway, we've got more than enough to work on: what matters more than the particular details of who's betraying who is the wholly impersonal world in which all of these deals are made, a world that is very specifically and important not presented as wicked and immoral; it is far scarier and more accurately amoral, made up of people so invested in money and trade that they have seemingly forgotten any actual real-world consequence to the sordid material in which they traffic. The closest anyone ever comes to making any sort of moral judgment one way or the other comes when the French team is visiting the TokyoAnime studio, and Hervé, watching a scene of a girl being raped by eels, cracks "It looks bad for her," a gag so lame he doesn't even let the translator explain it to the Japanese representatives, as Diane smiles absently and lights a cigarette. That is the kind of person we're looking at throughout demonlover: corporate bureaucrats so withdrawn from humanity that they aren't bothered by watching girlish cartoon figures getting raped except for their concern that the French authorities might view the characters' lack of pubic hair as a signifier that they're minors, or whose response to something as plainly evil as the Hellfire Club is to idly suggest that it's "fascinating". Though the gold standard in this regard is certainly the American Elaine's admission that the Hellfire Club is a well-made, enviable site, not without a trace of envy.

It's maybe difficult to work up moral indignation against the absence of moral consciousness, but Assayas is a director always up for a hard job, and his treatment of this milieu makes clear his absolute hatred for an international climate in which this kind of filth can be discussed solely in terms of its financial value in ways that could hardly be imagined in any other medium than the cinema. There are two visual cues in particular that dominate demonlover and propel its arguments far more readily than any amount of speaking could, not that any of the characters in the film are particularly inclined towards mouthing Assayas's arguments: the first of these is an icy-blue color palette that dominates virtually every moment of the film, washing out the characters and leaving them looking rather artificial and robotic. The actors' deliberately vacant performances help with this feeling, but it mostly comes down to the director's frequent cinematographer Denis Lenoir to blend the harsh under-lighting of film noir with this steely color scheme in a way that leaves the world of the film seeming mechanical and brutal. The other cue, and the more important I'd wager, although much more difficult to explain, is the careful positioning of the camera, which usually adopts a perspective quite separate from anyone onscreen, especially in the moments when we in the audience are watching the hentai or the Hellfire Club site: we're "between" the characters and the media, as it were, closer to the screen than any real-life viewer ever would be, so close that at times it loses definition. It's almost as though the director is rubbing our noses in the stuff that his characters barely even notice. In this regard, the grand final shot is a particular corker: inn which a victim of the Hellfire Club is staring blankly at the home viewer, who isn't even watching his screen - but we, the movie viewer, are looking straight at her, and she at us, just for a second until the camera shifts away. The implications are legion, but the one I like best is that Assayas and the character are both daring us to admit our own culpability in living in a media-soaked culture like the one in the film, a culture in which the moral value of media has been so sand-blasted away by multitasking and increasing audience savviness that we can too easily forget that there are ramifications to media consumption.

It's a nasty-minded attack on the plugged-in lifestyle that Westerners - I suspect Americans especially - have come to love so much since the mid-'90s, and I expect this has much to do with the cold reception given the film, or the odd fixation on its "narrative breakdown" after the half-way mark. It's not really a breakdown at all, though it switches gears from the easily-digested "companies suck" story of the first half; now we're confronted directly with the personal effects on the characters who live and breath in the environment that the first half defines. It's an elegant and, in hindsight, absolutely inevitable track-jumping that gives demonlover most of its truly unsettling impact, and it's not at all fun to grapple with a film that takes such nasty delight in pointing out how much human-scale damage is done by the modern world, especially given the film's whole-hearted refusal to offer any solutions or answers - like the problem of "business love unfettered capitalism" has any solutions! Now, all I've said has a single, major knock against it, which is that the precise world imagined by demonlover looks somewhat little like the internet-addled world of 2010, and it's not exactly like I remember 2002 being, either (of course, the idea of literal torture porn has only gained credibility since 2002). But there are enough discomfiting overlaps between Assayas's world and ours - the only flat-out error in representation I caught was when he showed an American teenager's room with a poster for the 1998 Godzilla - that it's doesn't take much squinting to see how the two could align; and the idea that corporations run amok are able to do incalculable damage to society and to the individuals caught up in those corporate cultures is something that sadly, is quite obvious even eight years later, even without the veil of a techno-thriller fable.