If you ask me, any movie with "rum" in the title should be about pirates, but I guess I'm just cooler than Claire Denis

I would like to make some grand statement about the characteristic aesthetic of French filmmaker Claire Denis, but I cannot do that. Just a couple of days ago, the only one of her films that I'd seen was 2004's The Intruder, and it's brilliant, the kind of movie that makes you want to learn everything you possibly can about a director - except maybe not, because I haven't.

Here's what I do know to be true: 35 Shots of Rum, Denis's 2008 feature only just making its slow way through the U.S. art theaters now, is unmistakably the work of the same woman who made The Intruder, and if I can make any kind of extrapolations about her art from that... ah, but I already said I wouldn't. Still, the temptation to do so is excruciating, because 35 Shots of Rum feels maddeningly opaque in a lot of ways, and it's easy and helpful to cling to any sort of context you can in that sort of situation. "No, no, see that's how a Claire Denis film works," I want to say about the studied lack of clear narrative progression, and the hair-raising peculiarities of the editing, which seems intended to make the flow of the movie as elliptical in its expression as a relative simple plot will allow. But I don't know if that's how a Claire Denis film works. It's how 35 Shots of Rum works, though, and all things considered it works very well, though it stops a few steps short of masterpiece status.

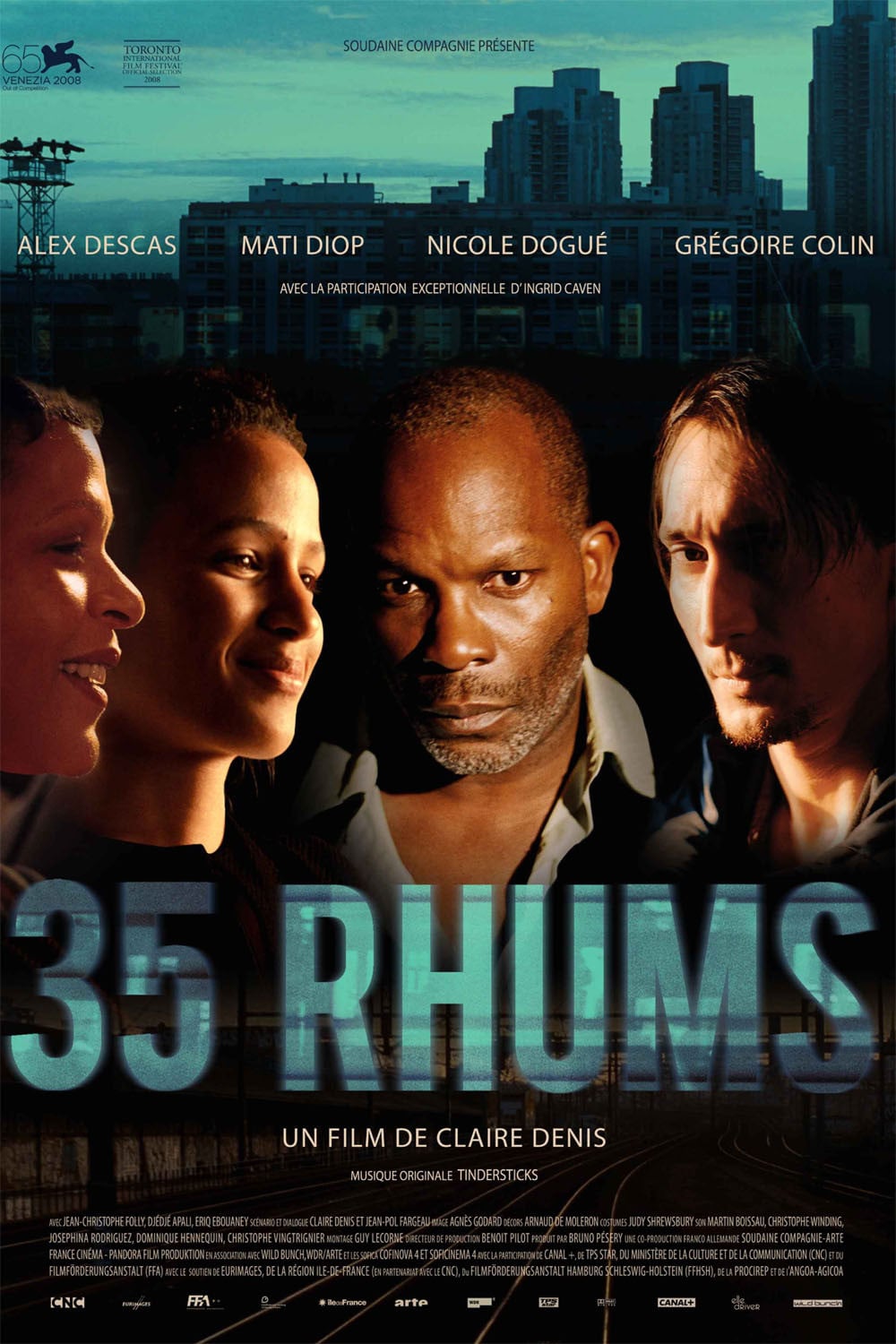

The easiest thing to do is explain what the film is about: 35 Shots of Rum is the study of how a loving family finds itself growing apart, not because the love has run out but because life just keeps nudging its way in between them. Simple enough, right? But the beauty of any great film is not "what" it does but "how" it does it, and therein lies the challenge and triumph of Denis's deliberately unconventional style. The main characters are Lionel (Alex Descas) and Joséphine (Mati Diop, making a luminous acting debut), a father and daughter living in an old apartment complex on the edge of Paris. He's a train operator, she is a university student, and the absence of her mother is at first neither noted nor terribly noteworthy. They live quietly and happily, a simple life that is more functional, perhaps, than tremendously satisfying. Each of them has a potential love affair waiting in the wings: she is pursued by Noé (Grégoire Colin), a slightly older man of unclear means or history (to the viewer, at least), with an old fat cat; while Lionel is under the constant attention of Gabrielle (Nicole Dogué), with whom it seems he had a fling in the past, or maybe Gabrielle wanted them to have had a fling in the past, and still does. That kind of almost but not quite understanding the details of a situation is key to Denis's art.

The point of 35 Shots of Rum, you see, is not in how the plot and situations develop over time, but in how the emotional realities of the moment develop over time. Take, as an example, the relationship between Joséphine and Noé. At the beginning of the film, it seems like there's not only a total lack of romantic history between the two, she's not tremendously receptive to his flirtations. And by the end of the film, that has ceased to be the case, but we aren't privy to most of the mechanics of that process. To say that Denis differs from a standard American-style filmmaker in this is a gross understatement; you can imagine a Hollywood treatment of this material focusing maniacally on the every little twist and turn in Jo and Noé's courtship, both because it is sexy and because it would allow for lots of intense fireworks between father and daughter. But Denis doesn't care about that sort of thing at all: we see only enough of the surrounding universe of 35 Shots of Rum to give a framework to the part of the movie that really matters, the slow deterioration of the family, which is shown in the film to have both a literal meaning and a more sentimentalised, metaphorical one. What matters about Jo and Noé is not that two young people fall in love per se. This sort of cross-sectional approach to the story is tremendously reminiscent of The Intruder, which also depicts events in terms of their emotional meaning rather than their narrative meaning, thought it is far less coherent (and as a result, far more abstractly beautiful) than 35 Shots of Rum.

This kind of filmmaking is, to say the least, not for all tastes. Judged by any customary rules of storytelling, 35 Shots of Rum is an incomprehensible train wreck, and all that means is that it shouldn't therefore be judged by customary rules; but not everyone is going to enjoy doing the work to get meaning out of this film (and on the basis of two films, I'm willing to say this much: Claire Denis is a hell of a lot of work). What I find to be a sometimes beautiful study of human relationships might seem so much pretentious flim-flam to you, and I have no real argument against that approach.

By no means is the film a flawless thing: at times its vagueness feels more like the result of a filmmaker who didn't always know precisely what her goals were, rather than the much more aggressive, revelatory opacity of The Intruder. This is especially true of the secondary characters, Noé and Gabrielle, who are significantly more thinly rendered than the leads (Noé especially), yet are given enough emphasis that this thinness is a bit more lazy than it is fascinating and deliberate, and Denis relies on the actors in both cases to do a great deal of the heavy lifting. Justifiably: they both give marvelous performances.

The film also generally lacks a certain poetic flair that might give its narrative vagueness more heft. I shouldn't put it that way. For the most part, the film gets enough mileage out its emotional arc that it seems uncouth to complain about it much at all. But there are at least a couple of moments - one involving the single best use of the Commodores' "Nightshift" that I can imagine, and one which I can't really describe for fear of spoilers, and a third is the final shot - where the film switches into another level so refined and breathtaking that I got a bit cross that the whole movie could have been like that. In the end, the resolutely quotidian nature of the drama and emotions in 35 Shots of Rum makes the film feel just ever so slightly shallow, compared to Denis's ambitions; but if every film about simple, quotidian issues was this daring in its execution, and this intuitive rather than explicit about what we're supposed to feel, world cinema would be in a much healthier place.

Here's what I do know to be true: 35 Shots of Rum, Denis's 2008 feature only just making its slow way through the U.S. art theaters now, is unmistakably the work of the same woman who made The Intruder, and if I can make any kind of extrapolations about her art from that... ah, but I already said I wouldn't. Still, the temptation to do so is excruciating, because 35 Shots of Rum feels maddeningly opaque in a lot of ways, and it's easy and helpful to cling to any sort of context you can in that sort of situation. "No, no, see that's how a Claire Denis film works," I want to say about the studied lack of clear narrative progression, and the hair-raising peculiarities of the editing, which seems intended to make the flow of the movie as elliptical in its expression as a relative simple plot will allow. But I don't know if that's how a Claire Denis film works. It's how 35 Shots of Rum works, though, and all things considered it works very well, though it stops a few steps short of masterpiece status.

The easiest thing to do is explain what the film is about: 35 Shots of Rum is the study of how a loving family finds itself growing apart, not because the love has run out but because life just keeps nudging its way in between them. Simple enough, right? But the beauty of any great film is not "what" it does but "how" it does it, and therein lies the challenge and triumph of Denis's deliberately unconventional style. The main characters are Lionel (Alex Descas) and Joséphine (Mati Diop, making a luminous acting debut), a father and daughter living in an old apartment complex on the edge of Paris. He's a train operator, she is a university student, and the absence of her mother is at first neither noted nor terribly noteworthy. They live quietly and happily, a simple life that is more functional, perhaps, than tremendously satisfying. Each of them has a potential love affair waiting in the wings: she is pursued by Noé (Grégoire Colin), a slightly older man of unclear means or history (to the viewer, at least), with an old fat cat; while Lionel is under the constant attention of Gabrielle (Nicole Dogué), with whom it seems he had a fling in the past, or maybe Gabrielle wanted them to have had a fling in the past, and still does. That kind of almost but not quite understanding the details of a situation is key to Denis's art.

The point of 35 Shots of Rum, you see, is not in how the plot and situations develop over time, but in how the emotional realities of the moment develop over time. Take, as an example, the relationship between Joséphine and Noé. At the beginning of the film, it seems like there's not only a total lack of romantic history between the two, she's not tremendously receptive to his flirtations. And by the end of the film, that has ceased to be the case, but we aren't privy to most of the mechanics of that process. To say that Denis differs from a standard American-style filmmaker in this is a gross understatement; you can imagine a Hollywood treatment of this material focusing maniacally on the every little twist and turn in Jo and Noé's courtship, both because it is sexy and because it would allow for lots of intense fireworks between father and daughter. But Denis doesn't care about that sort of thing at all: we see only enough of the surrounding universe of 35 Shots of Rum to give a framework to the part of the movie that really matters, the slow deterioration of the family, which is shown in the film to have both a literal meaning and a more sentimentalised, metaphorical one. What matters about Jo and Noé is not that two young people fall in love per se. This sort of cross-sectional approach to the story is tremendously reminiscent of The Intruder, which also depicts events in terms of their emotional meaning rather than their narrative meaning, thought it is far less coherent (and as a result, far more abstractly beautiful) than 35 Shots of Rum.

This kind of filmmaking is, to say the least, not for all tastes. Judged by any customary rules of storytelling, 35 Shots of Rum is an incomprehensible train wreck, and all that means is that it shouldn't therefore be judged by customary rules; but not everyone is going to enjoy doing the work to get meaning out of this film (and on the basis of two films, I'm willing to say this much: Claire Denis is a hell of a lot of work). What I find to be a sometimes beautiful study of human relationships might seem so much pretentious flim-flam to you, and I have no real argument against that approach.

By no means is the film a flawless thing: at times its vagueness feels more like the result of a filmmaker who didn't always know precisely what her goals were, rather than the much more aggressive, revelatory opacity of The Intruder. This is especially true of the secondary characters, Noé and Gabrielle, who are significantly more thinly rendered than the leads (Noé especially), yet are given enough emphasis that this thinness is a bit more lazy than it is fascinating and deliberate, and Denis relies on the actors in both cases to do a great deal of the heavy lifting. Justifiably: they both give marvelous performances.

The film also generally lacks a certain poetic flair that might give its narrative vagueness more heft. I shouldn't put it that way. For the most part, the film gets enough mileage out its emotional arc that it seems uncouth to complain about it much at all. But there are at least a couple of moments - one involving the single best use of the Commodores' "Nightshift" that I can imagine, and one which I can't really describe for fear of spoilers, and a third is the final shot - where the film switches into another level so refined and breathtaking that I got a bit cross that the whole movie could have been like that. In the end, the resolutely quotidian nature of the drama and emotions in 35 Shots of Rum makes the film feel just ever so slightly shallow, compared to Denis's ambitions; but if every film about simple, quotidian issues was this daring in its execution, and this intuitive rather than explicit about what we're supposed to feel, world cinema would be in a much healthier place.