Disney Animation: Cattle out the ol' wazoo

Here's a man who doesn't, I think, get nearly the respect he deserves, even among Disney animation buffs: Will Finn. Maybe because his career took him all over the place, and Disneyphilia tends to reward the lifers, like Glen Keane, Mark Henn, or Andreas Deja; Finn started out as one of Don Bluth's kids, doing some story work and animation on The Secret of NIMH; he drifted over to Filmation for a spell, working on 1987's Pinocchio and the Emperor of the Night, and doing some character design work on Happily Ever After, a Disney rip-off released in 1993. He finally stumbled into the House That Walt Built in time to do a bit of assistant animation for Oliver & Company, and by the time that Beauty and the Beast rolled around, he'd proven himself enough to be given a supervisory position, taking the lead on Cogsworth, the stuffy majordomo clock; he never got a hugely important character to shepherd to completion, although I don't think anyone would quibble if I said that Iago from Aladdin is a pretty memorable comic figure, and the worst you can say about his work on Laverne from The Hunchback of Notre Dame is that the animators did fine work with a character who didn't need to exist (and for what it's worth, I think she's the most appealing and best-performed of that film's gargoyle trio - faint praise, but praise). He was still occasionally given a chance to help develop stories (primarily Hunchback and Pocahontas), and finally, around the beginning of the '00s he had enough clout to get a project of his very own: a Western comedy inspired by the Pied Piper of Hamlin legend, titled Sweating Bullets.

Sadly, for Finn and the relatively green story man John Sanford to take over this foundering project (which was, supposedly, considered too grim or something like that), it meant that the directors already assigned, Mike Gabriel and Mike Giaimo, had to be cut loose. Gabriel was the more senior of those two men; he'd co-directed The Rescuers Down Under with Hendel Butoy, and Pocahontas with Eric Goldberg, and had been with the company as a character designer and animator since the dark days of The Black Cauldron. Giaimo's tenure with the company was a good deal shorted; limited exclusively to design work on Pocahontas. The two men had started in on Sweating Bullets soon after that project was completed, and I suppose that it was the lack of workable material after five years that led the executives to pull them from the project; nor can I get all teary-eyed about it. For if Sweating Bullets was going to be naught but a comic Western made by two of the chief creative minds behind that awkward, misguided attempt at historical romance, I think I should be just as happy letting it pass on by.

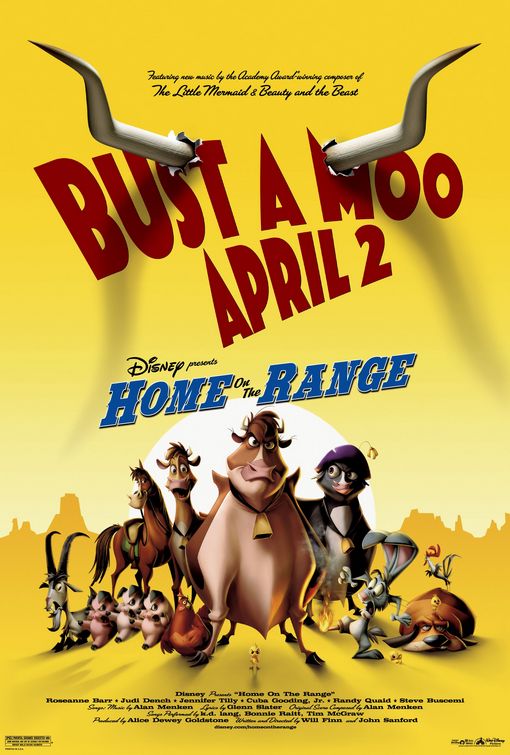

Finn and Sanford amped up the humor of the film considerably, confirming that their take was going to be rather more zingy than anything Gabriel and Giaimo were aiming for when it was announced that Roseanne, that noted comedienne whose formerly brilliant self-titled sitcom had crapped out in 1997 on a wave of startlingly unfunny self-indulgence. Eyebrows were raised at the announcement - I certainly remember that mine were - which was accompanied by a title change to Home on the Range, and a rather thorough re-build of the plot: instead of a bull fighting to save his herd from a rustler, it had turned into a trio of cows fighting for their owner's farm by capturing the rustler for the reward money. With, naturally, the expected shuffling about of supporting characters and the like.

This fairly major restructuring, committed in 2001, meant that Home on the Range could not possibly meet its holiday 2003 release date, and so the film was swapped with Brother Bear, and set for release on 2 April, 2004. That date is pretty darn telling, if you know how to read it. No Disney animated feature had been given a release date outside of the school-sensitive summer months, or the November/December holiday season, for nearly 30 years: the last was The Many Adventures of Winnie the Pooh, put out in the spring of 1977. And even that, let us not forget, was a compilation of three shorts that had been sitting around for as many as 11 years at that point - for an actual proper, high-budget feature to be given such a strange date, we have to back another 10 years, to The Jungle Book's release in mid-October, 1967. Let's be honest, that film - the first released after Walt's death - could have been put out just about any time, and the wave of nostalgia would all but guarantee it a huge box-office run.

That April 2, that can only mean one thing, especially coupled with the announcement from one year earlier, that Disney was shutting down its 2-D animation studio: Home on the Range was getting burned off, one last bit of business to attend to before turning off the electricity and leaving a forwarding address at the neighbors. And with the company so clearly registering their lack of interest in the film, critics and audiences followed suit: the film received virtually nothing but reviews full of studied indifference, and the movie grossed an icy $103 million on a reported $110 million budget - that's $103 million internationally, folks. Less than half of that came from U.S. theaters.

History has judged Home on the Range one last fart of ineptitude on Walt Disney Feature Animation's slide into pointlessness; but I do not share this judgment. It is assuredly a much weaker film than much of the studio's output, and there's very little about it that feels at all Disney-esque, but even conceding all of that, I find that what Finn and Sanford cobbled together is actually a fairly agreeable little comedy, hardly a film for the ages, and not at all worthy of being the last statement from Disney's decades-old traditional animation division - and this, I believe, has much to do with its smelly reputation. If you walked into a film knowing that the legacy of Steamboat Willie and Pinocchio, of Cinderella and Sleeping Beauty, of The Little Mermaid and Beauty and the Beast, was coming to its end, you'd probably expect or at least hope for something a whole hell of a lot different than Home on the Range. I did, certainly.

But really, taken from a more lofty, historical position, it's somewhat easy to see the film as the last in a strange little run of formula-busting Disney comedies - the run of Aladdin, Hercules, and The Emperor's New Groove wherein the animators experimented with styles increasingly alien to the well-established Disney house style, and the story artists played around in exceptionally modern gags and attitudes. Home on the Range is not as successful in it as any of those three, but I still admire that its sets out to do something different, and is unafraid to try things that might well fail.

Visually, this is the film in which Disney finally reconciled itself to a long-lost cousin: if the three films I just named (especially the last one) can be thought of as Disney's "Warner Bros. films", Home on the Range is their "UPA" film - United Productions of America being an animation studio founded in the 1940s by some of the refugees from the debilitating 1941 animators' strike at Disney, who had found that Walt's insistence on realistic animation was a needless self-inflicted wound that kept American animation from reaching its fullest expression. Inspired to a great degree by the physics-smashing animation over at Warner's, especially in the films directed by Chuck Jones, the UPA animators tried a number of things with limited animation, stripped-down character design, simple-unto-crude lines, and a deliberate, aggressively flat aesthetic; and they are rightfully seen as masters of a defiantly un-Disney variety of animation, having produced at least one all-time masterpiece with 1951's Gerald McBoing-Boing. Disney did not ignore this competition altogether: Ward Kimball and Charles A. Nichols's outstanding Toot, Whistle, Plunk, and Boom from 1953 cannot be anything other than a response to UPA's work, and the driving mentality of Disney's xerography years seems at least vaguely inspired by the intense lack of depth used by the other studio, which had slipped into tepid television work at the dawn of the 1960s.

Prior to 2004, though, Disney had never done too much playing around in UPA's sandbox - it was just too far removed from everything that defined the brand name. So for this reason if nothing else, Home on the Range will ever hold a tiny spot of warmth in my heart. What is that I mean, exactly, when I claim that the film uses UPA's style? The most obvious thing is the character design: all the cows and animals and people in the movie are outstandingly angular and line-driven, proportioned according to the most ridiculous cartoon logic, and above all, completely and utterly flat. It is one of the defining characteristics of Disney's animation since the 1930s that characters and scenes have depth to them: hence one of the most important innovations of CAPS was the ability to use much more rounded shading and lighting than ever before. If the animators are doing their job, you should never stop to think that you're watching character painted on celluloid (or on the digital equivalent), moving across flat paintings - why, they even named the most important technical innovation in traditional animation between 1989 and 2009 "Deep Canvas". But that's simply not the defining aesthetic in Home on the Range: you get the distinct feeling that if any of the characters turned towards the camera too swiftly, you would find that they are as flat as a playing card.

Thus freed from the tyranny of dimensionality and realism, the animators indulged in one of the most goofy, silly, cartoony projects made at Disney in years; its freewheeling ignorance of logic or physics even outdoes the deeply zany The Emperor's New Groove in this respect. By God, more of it! I say, even as I know that more of it is not likely forthcoming: if there's one thing the Disney executives are good at, it's running away from anything with a proven track record of poor box-office performance, and while a number of other things could explain the relative failure of these two particular films (namely, that 8-year-olds have never heard of UPA and probably couldn't tell you who Chuck Jones was if you gave them an encyclopedia of American animation), the lesson learned is always "screw with the formula, and you get screwed right back".

And mind you, it's not as if Home on the Range is some unimpeachable masterpiece of form: like Hercules, it commits the mistake of being much too fussy for its own aesthetic. In particular, the continued use of Deep Canvas for this project is quite the purest sort of idiocy: if you've committed, as the designers seemed to do, to angular, uni-dimensional characters, what possible reasoning could there be for plopping them in a richly-rendered 3-D environment full of swooping camera angles and all? At least the appearance of the landscapes is fairly cotangent with the appearance of the characters, being a good deal more simple and linear than the rich paintings by which Disney backgrounds are still best-known. Come to think of it, the relative cleanness and lack of detail in the backgrounds makes the use of depth effects even still more out-of-place and annoying.

The story and the characters in Home on the Range are both subordinated to its mood, which is one of the most consistently comic throughout the Disney canon - even the tender character moments are played for humor. Our three protagonists, the ones hunting down that rustler to save the Patch of Heaven ranch, are Maggie (Roseanne), loud-mouthed and vulgar, and the newcomer to the farm; Mrs. Caloway (Judi Dench), prim and British and in possession of a beloved hat; and Grace (Jennifer Tilly), a scattered New Agey type who doesn't understand why the other two can't get along. Gee, that's a new character dynamic. Except it really is new to Disney, when you think about it, so it still counts as formula-busting. Their barnyard is populated by a wide variety of comic stock characters given animal form: a cantankerous goat here, a nervous chicken there, a karate-fighting horse who longs to be the steed of a great Western hero over yonder (That would be Buck, boasting what I am inclined to call the only halfway decent Cuba Gooding, Jr. performance of the '00s). As for the rustler, he's a nasty sort by the name of Alameda Slim (Randy Quaid, or "Quaid the Lesser" as we call him in my house), and despite my good sense I can't help but regard him as a fairly delightful comic villain - certainly, he is conceived in the most bent spirit of nutso humor. His story is that he rustles cattle to drive ranchers out of business, only to buy their farms at auction under the name Y. O'Del; this is all an elaborate scheme to get revenge on those landowners who refused to hire him in earlier days, finding it quite stupid how he rounded up cattle by yodeling - for you see a skilled yodeler can bend any cow to his will, and Slim is the finest yodeler in the West. Which explains why he's also the finest rustler in the West. I expect that more people reading all that are vaguely disgusted by it than otherwise, but I don't know - "evil yodeler seeks revenge" is a charmingly psychotic hook to build a plot on, I think.

Slim's yodeling habit also permits Home on the Range the first honest-to-God musical production number since Mulan: titled "Yodel-Adle-Eedle-Idle-Oo", it's a real peculiar, wonderful affair - no doubt about it, the peak of the movie, and in my mind the best moment in Disney since Lilo & Stitch, three films earlier. Maybe even the first really good moment since Lilo & Stitch, at that. But anyway, the song, with music by a long-absent Alan Menken, happily returned to the Disney fold, and lyrics by Glenn Slater, is a weird self-aggrandising commentary on Slim's outstanding yodeling and cow-wrangling skills, with deliciously peculiar lines like "a pioneer Pied Piper in ten gallon underpants", married to some of the most self-assured non-representational animation we've seen in Disney in a long time - it is a sequence in which hypnotised cattle change color spontaneously and wander around in geometric progressions in a black space, and the only thing that I can possibly think to compare it to is some of the edgier shorts in the package films, or more familiarly, "Pink Elephants on Parade" from Dumbo.

Even outside of this highlight, Menken and Slater's songs are pretty decent, although none of them are used diegetically: k.d. lang performs "Little Patch of Heaven" to introduce and excuse the film, Bonnie Raitt has a plaintive and sort of draggy ballad, "Will the Sun Ever Shine Again", and Tim McGraw has the more anthemic "Wherever the Trail May Lead". Menken's ability to compose country tunes is not at all so sure as his gift for Broadway tunes, but at least it's not impersonal pop music this time.

Now, as I mentioned, comedy is this film's chief aim, and it is at some times more successful in this pursuit than others. To be honest, the tone is set pretty low, making sure that even the dullest child in the audience will have plenty to laugh at, and of course the corollary is that the a lot of the humor is really stupid. Now stupid humor can be funny, and it can just be, well, stupid; and Home on the Range splits itself between these two points right down the middle. Sometimes it's just noisy and chaotic for the sheer desperation of it. Mostly it's not - but only barely mostly. I will say this: nothing I can say will convince you of the rightness of casting Roseanne, Dench and Tilly in a movie about adventuresome cows, because I am not myself convinced of it - particularly in the case of the first woman.

All told, though, I like enough of the movie to give a passing grade: it is always pleasing to see the Disney animators stretching themselves, and I think it plain that they enjoyed the experience (you can always tell, somehow, when an animator is engaged by their work - there's a certain easiness in the line and an added dusting of play in the character expressions). A lot of good men and women signed their names to this one: Mark Henn (Grace and some minor characters), Duncan Marjoribanks (Mrs. Caloway), Bruce W. Smith (the ranch owner, Pearl), Russ Edmonds (Rico, a Clint Eastwood-inspired bounty hunter), Chris Buck (Maggie), and plenty of fine artists who didn't supervise, but simply did character animation - some, like Tony Bancroft, Andreas Deja and Anthony de Rosa, taking demotions, presumably so they could be part of it all, one last time, like tapping your sword on the king's shield before riding off to die.

Yet the tone is never elegiac, but always fun and creative and bright; of course, this film wasn't meant to be the last Disney animated feature of the 2-D age, and at least two projects in development were killed (one of those, The Snow Queen, is heavily rumored to be in production for a 2013 release). So if Home on the Range seems to be just one more sassy kid's comedy, that's all it was at the time. Thank God that it wasn't something like the mopey, trite Brother Bear that rang out the final gong on traditional Disney animation - at least going out with a silly, idiotic film like this proves that the animators and directors and story men were not ashamed of their chosen medium, and did not seek to euologise it. It was just business as usual, making a romp, a lark; a movie that works even if it never sets its sights higher than laughing toddlers and a thin grin of amusement on their parents. And at least it finds the artists pushing the artform one last time, and seeing in this their last shot at a legacy, putting maybe just a bit more sparkle into the character animation than they had for a least a few projects. It might be a fairly minor and modest conclusion to the story of Disney 2-D animation, but it is not an ignoble one, and if this isn't a masterpiece, at least it's an upswing from the mediocre Brother Bear and the dreadful Treasure Planet. And with that small comfort would the studio rest in piece.

Then again, maybe not.

Sadly, for Finn and the relatively green story man John Sanford to take over this foundering project (which was, supposedly, considered too grim or something like that), it meant that the directors already assigned, Mike Gabriel and Mike Giaimo, had to be cut loose. Gabriel was the more senior of those two men; he'd co-directed The Rescuers Down Under with Hendel Butoy, and Pocahontas with Eric Goldberg, and had been with the company as a character designer and animator since the dark days of The Black Cauldron. Giaimo's tenure with the company was a good deal shorted; limited exclusively to design work on Pocahontas. The two men had started in on Sweating Bullets soon after that project was completed, and I suppose that it was the lack of workable material after five years that led the executives to pull them from the project; nor can I get all teary-eyed about it. For if Sweating Bullets was going to be naught but a comic Western made by two of the chief creative minds behind that awkward, misguided attempt at historical romance, I think I should be just as happy letting it pass on by.

Finn and Sanford amped up the humor of the film considerably, confirming that their take was going to be rather more zingy than anything Gabriel and Giaimo were aiming for when it was announced that Roseanne, that noted comedienne whose formerly brilliant self-titled sitcom had crapped out in 1997 on a wave of startlingly unfunny self-indulgence. Eyebrows were raised at the announcement - I certainly remember that mine were - which was accompanied by a title change to Home on the Range, and a rather thorough re-build of the plot: instead of a bull fighting to save his herd from a rustler, it had turned into a trio of cows fighting for their owner's farm by capturing the rustler for the reward money. With, naturally, the expected shuffling about of supporting characters and the like.

This fairly major restructuring, committed in 2001, meant that Home on the Range could not possibly meet its holiday 2003 release date, and so the film was swapped with Brother Bear, and set for release on 2 April, 2004. That date is pretty darn telling, if you know how to read it. No Disney animated feature had been given a release date outside of the school-sensitive summer months, or the November/December holiday season, for nearly 30 years: the last was The Many Adventures of Winnie the Pooh, put out in the spring of 1977. And even that, let us not forget, was a compilation of three shorts that had been sitting around for as many as 11 years at that point - for an actual proper, high-budget feature to be given such a strange date, we have to back another 10 years, to The Jungle Book's release in mid-October, 1967. Let's be honest, that film - the first released after Walt's death - could have been put out just about any time, and the wave of nostalgia would all but guarantee it a huge box-office run.

That April 2, that can only mean one thing, especially coupled with the announcement from one year earlier, that Disney was shutting down its 2-D animation studio: Home on the Range was getting burned off, one last bit of business to attend to before turning off the electricity and leaving a forwarding address at the neighbors. And with the company so clearly registering their lack of interest in the film, critics and audiences followed suit: the film received virtually nothing but reviews full of studied indifference, and the movie grossed an icy $103 million on a reported $110 million budget - that's $103 million internationally, folks. Less than half of that came from U.S. theaters.

History has judged Home on the Range one last fart of ineptitude on Walt Disney Feature Animation's slide into pointlessness; but I do not share this judgment. It is assuredly a much weaker film than much of the studio's output, and there's very little about it that feels at all Disney-esque, but even conceding all of that, I find that what Finn and Sanford cobbled together is actually a fairly agreeable little comedy, hardly a film for the ages, and not at all worthy of being the last statement from Disney's decades-old traditional animation division - and this, I believe, has much to do with its smelly reputation. If you walked into a film knowing that the legacy of Steamboat Willie and Pinocchio, of Cinderella and Sleeping Beauty, of The Little Mermaid and Beauty and the Beast, was coming to its end, you'd probably expect or at least hope for something a whole hell of a lot different than Home on the Range. I did, certainly.

But really, taken from a more lofty, historical position, it's somewhat easy to see the film as the last in a strange little run of formula-busting Disney comedies - the run of Aladdin, Hercules, and The Emperor's New Groove wherein the animators experimented with styles increasingly alien to the well-established Disney house style, and the story artists played around in exceptionally modern gags and attitudes. Home on the Range is not as successful in it as any of those three, but I still admire that its sets out to do something different, and is unafraid to try things that might well fail.

Visually, this is the film in which Disney finally reconciled itself to a long-lost cousin: if the three films I just named (especially the last one) can be thought of as Disney's "Warner Bros. films", Home on the Range is their "UPA" film - United Productions of America being an animation studio founded in the 1940s by some of the refugees from the debilitating 1941 animators' strike at Disney, who had found that Walt's insistence on realistic animation was a needless self-inflicted wound that kept American animation from reaching its fullest expression. Inspired to a great degree by the physics-smashing animation over at Warner's, especially in the films directed by Chuck Jones, the UPA animators tried a number of things with limited animation, stripped-down character design, simple-unto-crude lines, and a deliberate, aggressively flat aesthetic; and they are rightfully seen as masters of a defiantly un-Disney variety of animation, having produced at least one all-time masterpiece with 1951's Gerald McBoing-Boing. Disney did not ignore this competition altogether: Ward Kimball and Charles A. Nichols's outstanding Toot, Whistle, Plunk, and Boom from 1953 cannot be anything other than a response to UPA's work, and the driving mentality of Disney's xerography years seems at least vaguely inspired by the intense lack of depth used by the other studio, which had slipped into tepid television work at the dawn of the 1960s.

Prior to 2004, though, Disney had never done too much playing around in UPA's sandbox - it was just too far removed from everything that defined the brand name. So for this reason if nothing else, Home on the Range will ever hold a tiny spot of warmth in my heart. What is that I mean, exactly, when I claim that the film uses UPA's style? The most obvious thing is the character design: all the cows and animals and people in the movie are outstandingly angular and line-driven, proportioned according to the most ridiculous cartoon logic, and above all, completely and utterly flat. It is one of the defining characteristics of Disney's animation since the 1930s that characters and scenes have depth to them: hence one of the most important innovations of CAPS was the ability to use much more rounded shading and lighting than ever before. If the animators are doing their job, you should never stop to think that you're watching character painted on celluloid (or on the digital equivalent), moving across flat paintings - why, they even named the most important technical innovation in traditional animation between 1989 and 2009 "Deep Canvas". But that's simply not the defining aesthetic in Home on the Range: you get the distinct feeling that if any of the characters turned towards the camera too swiftly, you would find that they are as flat as a playing card.

Thus freed from the tyranny of dimensionality and realism, the animators indulged in one of the most goofy, silly, cartoony projects made at Disney in years; its freewheeling ignorance of logic or physics even outdoes the deeply zany The Emperor's New Groove in this respect. By God, more of it! I say, even as I know that more of it is not likely forthcoming: if there's one thing the Disney executives are good at, it's running away from anything with a proven track record of poor box-office performance, and while a number of other things could explain the relative failure of these two particular films (namely, that 8-year-olds have never heard of UPA and probably couldn't tell you who Chuck Jones was if you gave them an encyclopedia of American animation), the lesson learned is always "screw with the formula, and you get screwed right back".

And mind you, it's not as if Home on the Range is some unimpeachable masterpiece of form: like Hercules, it commits the mistake of being much too fussy for its own aesthetic. In particular, the continued use of Deep Canvas for this project is quite the purest sort of idiocy: if you've committed, as the designers seemed to do, to angular, uni-dimensional characters, what possible reasoning could there be for plopping them in a richly-rendered 3-D environment full of swooping camera angles and all? At least the appearance of the landscapes is fairly cotangent with the appearance of the characters, being a good deal more simple and linear than the rich paintings by which Disney backgrounds are still best-known. Come to think of it, the relative cleanness and lack of detail in the backgrounds makes the use of depth effects even still more out-of-place and annoying.

The story and the characters in Home on the Range are both subordinated to its mood, which is one of the most consistently comic throughout the Disney canon - even the tender character moments are played for humor. Our three protagonists, the ones hunting down that rustler to save the Patch of Heaven ranch, are Maggie (Roseanne), loud-mouthed and vulgar, and the newcomer to the farm; Mrs. Caloway (Judi Dench), prim and British and in possession of a beloved hat; and Grace (Jennifer Tilly), a scattered New Agey type who doesn't understand why the other two can't get along. Gee, that's a new character dynamic. Except it really is new to Disney, when you think about it, so it still counts as formula-busting. Their barnyard is populated by a wide variety of comic stock characters given animal form: a cantankerous goat here, a nervous chicken there, a karate-fighting horse who longs to be the steed of a great Western hero over yonder (That would be Buck, boasting what I am inclined to call the only halfway decent Cuba Gooding, Jr. performance of the '00s). As for the rustler, he's a nasty sort by the name of Alameda Slim (Randy Quaid, or "Quaid the Lesser" as we call him in my house), and despite my good sense I can't help but regard him as a fairly delightful comic villain - certainly, he is conceived in the most bent spirit of nutso humor. His story is that he rustles cattle to drive ranchers out of business, only to buy their farms at auction under the name Y. O'Del; this is all an elaborate scheme to get revenge on those landowners who refused to hire him in earlier days, finding it quite stupid how he rounded up cattle by yodeling - for you see a skilled yodeler can bend any cow to his will, and Slim is the finest yodeler in the West. Which explains why he's also the finest rustler in the West. I expect that more people reading all that are vaguely disgusted by it than otherwise, but I don't know - "evil yodeler seeks revenge" is a charmingly psychotic hook to build a plot on, I think.

Slim's yodeling habit also permits Home on the Range the first honest-to-God musical production number since Mulan: titled "Yodel-Adle-Eedle-Idle-Oo", it's a real peculiar, wonderful affair - no doubt about it, the peak of the movie, and in my mind the best moment in Disney since Lilo & Stitch, three films earlier. Maybe even the first really good moment since Lilo & Stitch, at that. But anyway, the song, with music by a long-absent Alan Menken, happily returned to the Disney fold, and lyrics by Glenn Slater, is a weird self-aggrandising commentary on Slim's outstanding yodeling and cow-wrangling skills, with deliciously peculiar lines like "a pioneer Pied Piper in ten gallon underpants", married to some of the most self-assured non-representational animation we've seen in Disney in a long time - it is a sequence in which hypnotised cattle change color spontaneously and wander around in geometric progressions in a black space, and the only thing that I can possibly think to compare it to is some of the edgier shorts in the package films, or more familiarly, "Pink Elephants on Parade" from Dumbo.

Even outside of this highlight, Menken and Slater's songs are pretty decent, although none of them are used diegetically: k.d. lang performs "Little Patch of Heaven" to introduce and excuse the film, Bonnie Raitt has a plaintive and sort of draggy ballad, "Will the Sun Ever Shine Again", and Tim McGraw has the more anthemic "Wherever the Trail May Lead". Menken's ability to compose country tunes is not at all so sure as his gift for Broadway tunes, but at least it's not impersonal pop music this time.

Now, as I mentioned, comedy is this film's chief aim, and it is at some times more successful in this pursuit than others. To be honest, the tone is set pretty low, making sure that even the dullest child in the audience will have plenty to laugh at, and of course the corollary is that the a lot of the humor is really stupid. Now stupid humor can be funny, and it can just be, well, stupid; and Home on the Range splits itself between these two points right down the middle. Sometimes it's just noisy and chaotic for the sheer desperation of it. Mostly it's not - but only barely mostly. I will say this: nothing I can say will convince you of the rightness of casting Roseanne, Dench and Tilly in a movie about adventuresome cows, because I am not myself convinced of it - particularly in the case of the first woman.

All told, though, I like enough of the movie to give a passing grade: it is always pleasing to see the Disney animators stretching themselves, and I think it plain that they enjoyed the experience (you can always tell, somehow, when an animator is engaged by their work - there's a certain easiness in the line and an added dusting of play in the character expressions). A lot of good men and women signed their names to this one: Mark Henn (Grace and some minor characters), Duncan Marjoribanks (Mrs. Caloway), Bruce W. Smith (the ranch owner, Pearl), Russ Edmonds (Rico, a Clint Eastwood-inspired bounty hunter), Chris Buck (Maggie), and plenty of fine artists who didn't supervise, but simply did character animation - some, like Tony Bancroft, Andreas Deja and Anthony de Rosa, taking demotions, presumably so they could be part of it all, one last time, like tapping your sword on the king's shield before riding off to die.

Yet the tone is never elegiac, but always fun and creative and bright; of course, this film wasn't meant to be the last Disney animated feature of the 2-D age, and at least two projects in development were killed (one of those, The Snow Queen, is heavily rumored to be in production for a 2013 release). So if Home on the Range seems to be just one more sassy kid's comedy, that's all it was at the time. Thank God that it wasn't something like the mopey, trite Brother Bear that rang out the final gong on traditional Disney animation - at least going out with a silly, idiotic film like this proves that the animators and directors and story men were not ashamed of their chosen medium, and did not seek to euologise it. It was just business as usual, making a romp, a lark; a movie that works even if it never sets its sights higher than laughing toddlers and a thin grin of amusement on their parents. And at least it finds the artists pushing the artform one last time, and seeing in this their last shot at a legacy, putting maybe just a bit more sparkle into the character animation than they had for a least a few projects. It might be a fairly minor and modest conclusion to the story of Disney 2-D animation, but it is not an ignoble one, and if this isn't a masterpiece, at least it's an upswing from the mediocre Brother Bear and the dreadful Treasure Planet. And with that small comfort would the studio rest in piece.

Then again, maybe not.