Disney Animation: Incredible as it is inept

Walt Disney Production's 1973 Robin Hood, I must confess, holds a very important place in my heart. It was while re-watching the film as a young person (for I had a marked tendency to watch Disney films very often in youth) that I first realised that there was such a thing as a Disney picture that I really didn't like very much. And so do I continue to not like it very much; in fact I should be happy to call it the worst feature that the studio made to the end of the 1970s, replacing the heretofore unassailable Saludos Amigos at the bottom of the heap. I say this, but only with some degree of regret and sorrow. After all, a good friend of mine declared (in college, but I do not know that he's changed his mind) that Robin Hood was his favorite of all Disney films; another friend goes even further to call it one of his favorite movies of all time. Neither of these men are what you would call cinematic imbeciles, nor are they alone in people I know in harboring fondness towards the movie. Besides, to quickly scan its IMDb user ratings - hardly a bastion of critical genius, but it's a good way to quickly gauge the general impression that the anglophone film-lovers have of a particular work- you would get the impression that Robin Hood is one of the all-time masterpieces of animation (you would also get the impression that Disney history includes only this movie and those made after 1989). Prior to re-watching it for this review, I began to seriously doubt my memory: I couldn't possibly really dislike any movie that much if so many people seemed to regard it with such affection, right? Well, I've seen it again, for the first time in a good decade, and I stand by my initial response: this is a pretty damn dreadful 80 minutes - at the time of its production, the longest Disney feature since Fantasia, and only the fourth to hit the 80-minute mark - serving little purpose other than to mark another layer of suck in the inordinately swift decline in the studio's quality following its founder's death late in 1966.

Surprisingly, the film actually has its roots in a project that was abandoned in its cradle while Walt was still alive; there had been some extremely preliminary work done on a project involving the French folk character Reynard the Fox, but the boss eventually nixed it, concerned that Reynard wasn't a sufficiently familiar character to carry a feature. Many years later, Ken Anderson, one of the company's oldest production designers and story men, recalled this aborted attempt to make an adventure tale with a talking fox, and bent it into a very different direction altogether: he came up with a whole cast of anthropomorphic woodland critters to populate an animal kingdom retelling of the legend of England's famous communist thief. Other than the idea and the character designs, however, Anderson wasn't responsible for the rest of the story development; that task fell to Larry Clemmons, himself no spring chicken when it came to concocting animated narratives. Once again, the film was directed by Wolfgang Reitherman, who with The Aristocats had also established himself as the de facto "New Walt" producing all of the studio's features throughout the decade. The idea of a whole cast of bipedal animals was, at the least, something new for the animators, and in theory the film should have been an opportunity for them to stretch out and do something new.

Unfortunately, the rot that had infected the animation studio after Walt's death wouldn't be shaken off so readily; Reitherman might have stepped in as producer, but he could not replicate his predecessor's all-encompassing vision; and everything that The Aristocats did poorly, Robin Hood did worse, as well as coming up with some brand new flaws all its own. Save in one case: the fifth feature made using the xerography technology, Robin Hood is also at least arguably the film that really started to iron out the kinks that this technology entailed, and while it still has a particularly graphic look to it, and the unusually heavy lines found in The Aristocats are still present, it is otherwise the cleanest-looking of all the xerography films made to that point.

I might as well begin with the single biggest issue that, love the movie or hate it, is unquestionably the most obvious characteristic of Robin Hood: the animal thing. It is sometimes advanced that this is a significant work for being, after Bambi, the second of only three Disney features with an all-animal cast; but even those making this argument invariable feel the need to qualify the degree to which this actually applies. As well they ought, for there's nothing about Robin Hood that demands a universe of anthropomorphic animals, nor does the film make any attempt whatsoever to exploit the fact, except in the case of Sir Hiss the snake, loyal advisor to the usurping Prince John; his serpentine form is frequently pointed out, and often made the butt of physical gags. I cannot regard it as a coincidence that these gags are without fail the most successful in the film, and thus wonder how much better the film would have worked if the film had emphasised everyone else's animal characteristics.

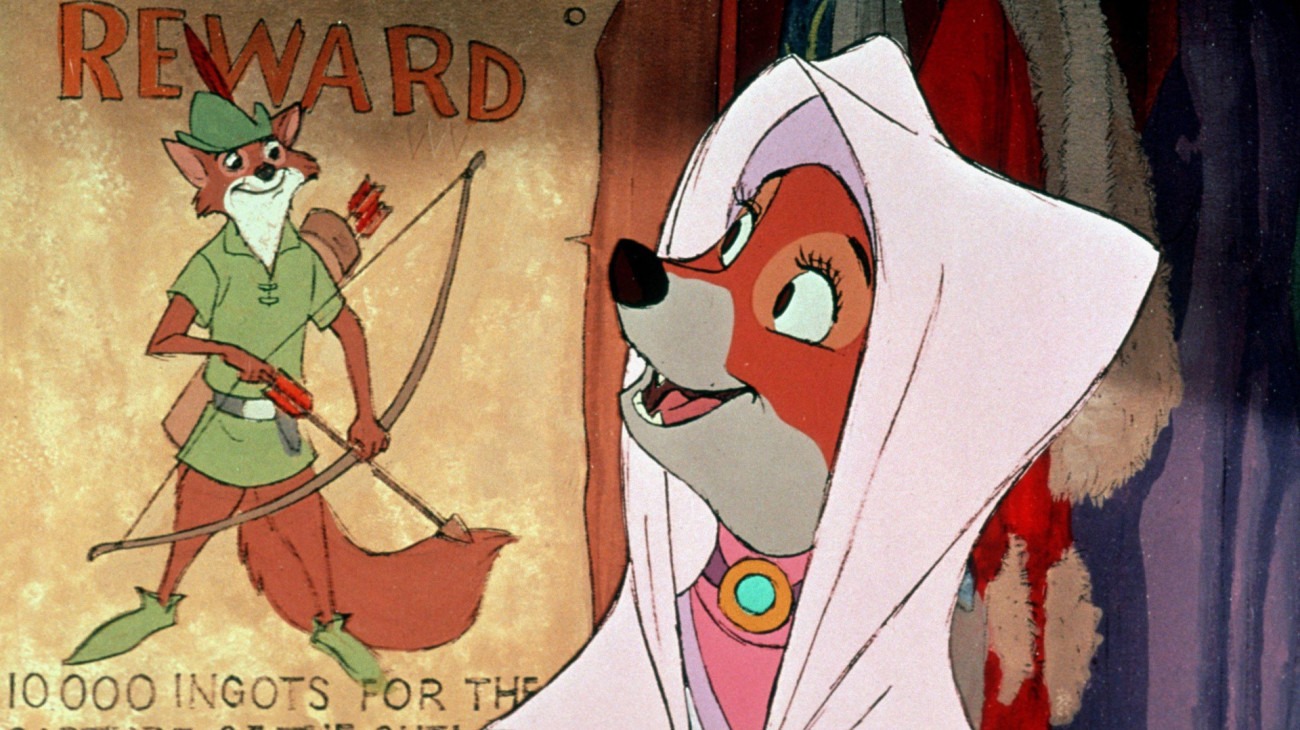

As it stands, there's precious little reason why this very prominent decision needed to be made. At the very least, the choice of which animal should represent each major character is made with some care: Robin Hood, being a crafty and cunning sort, certainly makes sense as a fox; so too is it reasonable that the avaricious Sheriff of Nottingham would be a wolf. That Maid Marian would have to be a vixen was no doubt dictated by Walt Disney Production's fear of inter-species romance (a concern that did not apply to the Golden Age shorts, in which Horace Horsecollar and Clarabelle Cow were uncontroversially presented as a couple); though this does not account for how she could therefore be the niece of King Richard I, who befitting his sobriquet "Lionheart" is, obviously a lion. This naturally means that his brother, John, would have to be a lion as well. Why Little John should be a bear is not maybe so obvious: because he's big and strong, and, um, cuddly? Perhaps there was a gay underground in Sherwood Forest that we are not otherwise privy to.

But why the inhabitants of Nottingham should be rabbits and dogs and raccoons and the like is certainly not obvious, any more than the reason why Friar Tuck should be a badger. And I want to stress that the mere fact that it makes some kind of vague sense for e.g. Robin to be a fox, that doesn't necessarily justify the fact that he is a fox; there is not one joke, plot-point, or even a single line of dialogue that would have to be altered if he were a man instead. I'm going to go out on a limb, and suggest that maybe the reason is that the studio was adapting a story that had already been given definitive cinematic form. Previously, it was the case that their films were in the main taken from source material that had never been filmed at all, or if it had been (as in the case of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs and Alice in Wonderland especially), the previous film was of no especial significance. With Robin Hood, though, Disney was treading on ground that many feet had stepped on before; without even glancing at a list of adaptations that preceded 1973, I can confidently identify the 1950s British TV series as a well-loved version of the story; and then there is a certain 1938 film, The Adventures of Robin Hood, that just so happens to be a masterpiece, one of the all-time great examples of Technicolor cinematography and a cracking great adventure film to boot. Maybe it was the case that Disney wanted to do something that would set their version apart. I really can't say.

The only other idea I can come up, and frankly it's at least as likely, is a great deal more cynical: Robin Hood was populated by animals because kids like animals. And there was never before a Disney feature that so blatantly catered to a juvenile audience, without making even the slightest attempt to entertain the grown-ups unless it so happens that they liked silly, Saturday morning cartoon-level hijinks (I can only think of one - maybe two - that would match this level of kids' movie shallowness). There is no attempt to exploit the animal characteristics of the characters because there doesn't need to be - the heavy lifting is already done when the child watching a TV ad shouts, "Mommy, I want to see the funny movie with the fox!"

That it's so transparently a kid's movie is an excuse to paper over quite a few holes that really start to nag if you give them any real thought: like, why do some of the characters speak with English accents, but some sound like character actors from a Western (I adore Andy Devine, but my God, he has too distinct a voice to be plopped indiscriminately into anything: try watching the 1936 Romeo and Juliet without getting the giggles at his performance as Peter, I dare you)? No, it doesn't "matter", but it speaks to a lack of care that would have never passed muster even ten years earlier: just look at One Hundred and One Dalmatians and wonder what atrocities might have befallen that great movie if 'twere made in the age of celebrity stunt casting.

On the other hand, stunt casting is the only thing that saves Robin Hood from committing the most egregious sin of The Aristocats: lame villains. As scripted, Prince John is even more pointless a bad guy than Edgar the butler was: one of the first things we learn about him is that he has mommy issues which send him into a neurotic fit, tugging his ear and sucking his thumb (he's also the first of Disney's male villains who may or may not be coded homosexuals - but I have to say, there are enough reasons to disdain the company's problematic representations throughout the years without hunting down phantom homophobia). No way does Robin Hood have a problem stopping this bozo; even when he's tied up and surrounded by rhinos with axes, we never ever fear for his life. When a villain is this transparently ineffectual, he must become a comic relief figure; must perhaps even become the sympathetic character who gets beat up by the dick hero - has anyone ever liked Bugs Bunny more than Elmer Fudd? And thankfully, Prince John and Sir Hiss do eventually emerge as the most likable - the only likable - characters in Robin Hood, thanks mainly to some absolutely canny celebrity casting: Peter Ustinov as John, and the mostly forgotten British comic character actor Terry-Thomas as Hiss (who shares his performer's characteristic tooth gap). They're not the only famous voices to be heard: Phil Harris once again makes his presence felt as Little John (though he's deprived the chance to sing a crappy jazz song this time), Devine and Pat Buttram (the Sheriff) represent the Western contingent, and the somewhat noteworthy stage actor Brian Bedford plays Robin. But they're the only ones that fit very well, and Ustinov particularly manages to sell what would otherwise be a horribly feeble bad guy as a fine object of comic abuse. Prince John functions, ultimately, rather like Captain Hook in Peter Pan, though due mostly to the acting and not to the story.

But I was talking about the kiddie-picture trashiness of the piece, non? The plot is nothing to speak of, just another in the intermittent run of Disney films that substitute an episodic series of comic sequences for a proper narrative throughline. And the songs are an outrageous joke. Having made two "jazz" films in a row, the rather dubious choice was made to make Robin Hood a "folk" film. Then the even more dubious choice was made to have Roger Miller provide the folk songs, one of which later gained a second life when it was sped up and made the soundtrack to the early internet sensation Hamster Dance. There are two non-Miller songs on the soundtrack: Johnny Mercer's "The Phony King of England", which is a fairly poppy, fun bit of nonsense, and Floyd Huddleston and George Bruns's awful, Oscar-nominated "Love", a romantic ballad so insipid that one's ears practically shut down in protest.

God, even the opening credits smack of cheapness: they're presented in a plain sans serif font that says "the medieval adventures of Robin Hood" somewhat less than "corporate letterhead".

It should not be surprising that the animation is of reasonably diminished quality, on top of everything else: for when an animated picture is made for loose change and aimed at an indiscriminate child audience, that is of course the first thing to suffer. It cannot have helped matters that, by the time the film was in production, most of Disney's veteran animation staff was getting pretty old - the youngest of the six remaining Nine Old Men was 61 when the movie was released. I suspect indeed that they would have retired before this point, except that with Walt gone there was the idea that some continuity had to be maintained; but they really had nothing new to say with the art form, and the chief feeling one gets from the animation in Robin Hood is one of fatigue: these were men who had worked on the most expansive, ambitious animations in American history, and now they were being asked to make a matinee picture. I don't blame them for the general stiffness that pervades the film, particularly Robin himself - only Prince John (directed by Ollie Johnston, with some input from Frank Thomas) is a particularly well-achieved bit of character animation, and I imagine that Ustinov's performance helped with that. Even the great Milt Kahl, responsible for the Sheriff, couldn't do much with the character, who is at any rate marked by a truly outrageous amount of recycled animation from scene to scene.

Boy, is there ever a problem with recycling in Robin Hood: it might have the most re-used animation of any Disney feature, especially in the "Phony King of England" scene. A healthy chunk of the "I Wanna Be Like You" dance from The Jungle Book is reworked, plus some dancing from The Aristocats; most notoriously, Marian's movements for a good 15 seconds are taken straight from Snow White herself - which has the benefit, at least, of making Marian look better in those seconds than anyone else in the whole movie. Design elements are stolen from a number of movies, some sound effects are taken from Cinderella, and that doesn't address how much of the animation is reused with the film itself. It's not laziness, it's cost-cutting, but it does certainly add to the feeling that what we're watching could just as easily have been put together by Filmation with a better background artist (I'll say this, at least: the effects animation is top notch. But the effects animation always is in a Disney film, no matter what else is wrong; and that is why I rarely mention it).

At the same time as the old guard was getting, um, old, there was some fresh blood coming in: Eric Larson, former animator and one of the Nine Old Men, quit the animation department during this film's production (he hadn't been a directing animator in some time) to head up the new training wing of the studio, finding new talent and teaching them how to do what the Disney animators in the prime did better than anyone else. These younger generations of artists had been around for a while, of course, but it was with Robin Hood that they first got to take charge. Not as directing animators, of course, but as featured character animators: among them was a man named Don Bluth, given his first on-screen credit after more than a decade with Disney; this fellow's development would be of keen importance to the studio, though not in the way the company might have liked.

The kids couldn't do much, though, for the project was hobbled by a low budget and low expectations, and when it was finally dropped into theaters, it was as a sheer commercial object, with as little artistry as anything in Disney's history - not even the bizarre psychedelia of "Ev'rybody Wants to Be a Cat" to save it. It is said that Ken Anderson was heartbroken to see what his characters had been reduced to, as well he might be.

But the film did a bit of business - more than The Aristocats, at least - and it achieved its tiny goal of delighting young audiences, and presumably adult audiences as well who were sufficiently determined to have a fun time laughing at silly critters. I would hate to deny it at least that success - it is "fun", in an unusually disposable way. More importantly, it seems to have kicked the animators into high gear, because they quickly started on the next feature project, one that would not be any kind of masterpiece, but certainly represented a better achievement on every important level: more interesting, sympathetic characters, brought to life with higher-quality animation and design. Robin Hood may have been a low ebb, but at least it was not protracted.

Surprisingly, the film actually has its roots in a project that was abandoned in its cradle while Walt was still alive; there had been some extremely preliminary work done on a project involving the French folk character Reynard the Fox, but the boss eventually nixed it, concerned that Reynard wasn't a sufficiently familiar character to carry a feature. Many years later, Ken Anderson, one of the company's oldest production designers and story men, recalled this aborted attempt to make an adventure tale with a talking fox, and bent it into a very different direction altogether: he came up with a whole cast of anthropomorphic woodland critters to populate an animal kingdom retelling of the legend of England's famous communist thief. Other than the idea and the character designs, however, Anderson wasn't responsible for the rest of the story development; that task fell to Larry Clemmons, himself no spring chicken when it came to concocting animated narratives. Once again, the film was directed by Wolfgang Reitherman, who with The Aristocats had also established himself as the de facto "New Walt" producing all of the studio's features throughout the decade. The idea of a whole cast of bipedal animals was, at the least, something new for the animators, and in theory the film should have been an opportunity for them to stretch out and do something new.

Unfortunately, the rot that had infected the animation studio after Walt's death wouldn't be shaken off so readily; Reitherman might have stepped in as producer, but he could not replicate his predecessor's all-encompassing vision; and everything that The Aristocats did poorly, Robin Hood did worse, as well as coming up with some brand new flaws all its own. Save in one case: the fifth feature made using the xerography technology, Robin Hood is also at least arguably the film that really started to iron out the kinks that this technology entailed, and while it still has a particularly graphic look to it, and the unusually heavy lines found in The Aristocats are still present, it is otherwise the cleanest-looking of all the xerography films made to that point.

I might as well begin with the single biggest issue that, love the movie or hate it, is unquestionably the most obvious characteristic of Robin Hood: the animal thing. It is sometimes advanced that this is a significant work for being, after Bambi, the second of only three Disney features with an all-animal cast; but even those making this argument invariable feel the need to qualify the degree to which this actually applies. As well they ought, for there's nothing about Robin Hood that demands a universe of anthropomorphic animals, nor does the film make any attempt whatsoever to exploit the fact, except in the case of Sir Hiss the snake, loyal advisor to the usurping Prince John; his serpentine form is frequently pointed out, and often made the butt of physical gags. I cannot regard it as a coincidence that these gags are without fail the most successful in the film, and thus wonder how much better the film would have worked if the film had emphasised everyone else's animal characteristics.

As it stands, there's precious little reason why this very prominent decision needed to be made. At the very least, the choice of which animal should represent each major character is made with some care: Robin Hood, being a crafty and cunning sort, certainly makes sense as a fox; so too is it reasonable that the avaricious Sheriff of Nottingham would be a wolf. That Maid Marian would have to be a vixen was no doubt dictated by Walt Disney Production's fear of inter-species romance (a concern that did not apply to the Golden Age shorts, in which Horace Horsecollar and Clarabelle Cow were uncontroversially presented as a couple); though this does not account for how she could therefore be the niece of King Richard I, who befitting his sobriquet "Lionheart" is, obviously a lion. This naturally means that his brother, John, would have to be a lion as well. Why Little John should be a bear is not maybe so obvious: because he's big and strong, and, um, cuddly? Perhaps there was a gay underground in Sherwood Forest that we are not otherwise privy to.

But why the inhabitants of Nottingham should be rabbits and dogs and raccoons and the like is certainly not obvious, any more than the reason why Friar Tuck should be a badger. And I want to stress that the mere fact that it makes some kind of vague sense for e.g. Robin to be a fox, that doesn't necessarily justify the fact that he is a fox; there is not one joke, plot-point, or even a single line of dialogue that would have to be altered if he were a man instead. I'm going to go out on a limb, and suggest that maybe the reason is that the studio was adapting a story that had already been given definitive cinematic form. Previously, it was the case that their films were in the main taken from source material that had never been filmed at all, or if it had been (as in the case of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs and Alice in Wonderland especially), the previous film was of no especial significance. With Robin Hood, though, Disney was treading on ground that many feet had stepped on before; without even glancing at a list of adaptations that preceded 1973, I can confidently identify the 1950s British TV series as a well-loved version of the story; and then there is a certain 1938 film, The Adventures of Robin Hood, that just so happens to be a masterpiece, one of the all-time great examples of Technicolor cinematography and a cracking great adventure film to boot. Maybe it was the case that Disney wanted to do something that would set their version apart. I really can't say.

The only other idea I can come up, and frankly it's at least as likely, is a great deal more cynical: Robin Hood was populated by animals because kids like animals. And there was never before a Disney feature that so blatantly catered to a juvenile audience, without making even the slightest attempt to entertain the grown-ups unless it so happens that they liked silly, Saturday morning cartoon-level hijinks (I can only think of one - maybe two - that would match this level of kids' movie shallowness). There is no attempt to exploit the animal characteristics of the characters because there doesn't need to be - the heavy lifting is already done when the child watching a TV ad shouts, "Mommy, I want to see the funny movie with the fox!"

That it's so transparently a kid's movie is an excuse to paper over quite a few holes that really start to nag if you give them any real thought: like, why do some of the characters speak with English accents, but some sound like character actors from a Western (I adore Andy Devine, but my God, he has too distinct a voice to be plopped indiscriminately into anything: try watching the 1936 Romeo and Juliet without getting the giggles at his performance as Peter, I dare you)? No, it doesn't "matter", but it speaks to a lack of care that would have never passed muster even ten years earlier: just look at One Hundred and One Dalmatians and wonder what atrocities might have befallen that great movie if 'twere made in the age of celebrity stunt casting.

On the other hand, stunt casting is the only thing that saves Robin Hood from committing the most egregious sin of The Aristocats: lame villains. As scripted, Prince John is even more pointless a bad guy than Edgar the butler was: one of the first things we learn about him is that he has mommy issues which send him into a neurotic fit, tugging his ear and sucking his thumb (he's also the first of Disney's male villains who may or may not be coded homosexuals - but I have to say, there are enough reasons to disdain the company's problematic representations throughout the years without hunting down phantom homophobia). No way does Robin Hood have a problem stopping this bozo; even when he's tied up and surrounded by rhinos with axes, we never ever fear for his life. When a villain is this transparently ineffectual, he must become a comic relief figure; must perhaps even become the sympathetic character who gets beat up by the dick hero - has anyone ever liked Bugs Bunny more than Elmer Fudd? And thankfully, Prince John and Sir Hiss do eventually emerge as the most likable - the only likable - characters in Robin Hood, thanks mainly to some absolutely canny celebrity casting: Peter Ustinov as John, and the mostly forgotten British comic character actor Terry-Thomas as Hiss (who shares his performer's characteristic tooth gap). They're not the only famous voices to be heard: Phil Harris once again makes his presence felt as Little John (though he's deprived the chance to sing a crappy jazz song this time), Devine and Pat Buttram (the Sheriff) represent the Western contingent, and the somewhat noteworthy stage actor Brian Bedford plays Robin. But they're the only ones that fit very well, and Ustinov particularly manages to sell what would otherwise be a horribly feeble bad guy as a fine object of comic abuse. Prince John functions, ultimately, rather like Captain Hook in Peter Pan, though due mostly to the acting and not to the story.

But I was talking about the kiddie-picture trashiness of the piece, non? The plot is nothing to speak of, just another in the intermittent run of Disney films that substitute an episodic series of comic sequences for a proper narrative throughline. And the songs are an outrageous joke. Having made two "jazz" films in a row, the rather dubious choice was made to make Robin Hood a "folk" film. Then the even more dubious choice was made to have Roger Miller provide the folk songs, one of which later gained a second life when it was sped up and made the soundtrack to the early internet sensation Hamster Dance. There are two non-Miller songs on the soundtrack: Johnny Mercer's "The Phony King of England", which is a fairly poppy, fun bit of nonsense, and Floyd Huddleston and George Bruns's awful, Oscar-nominated "Love", a romantic ballad so insipid that one's ears practically shut down in protest.

God, even the opening credits smack of cheapness: they're presented in a plain sans serif font that says "the medieval adventures of Robin Hood" somewhat less than "corporate letterhead".

It should not be surprising that the animation is of reasonably diminished quality, on top of everything else: for when an animated picture is made for loose change and aimed at an indiscriminate child audience, that is of course the first thing to suffer. It cannot have helped matters that, by the time the film was in production, most of Disney's veteran animation staff was getting pretty old - the youngest of the six remaining Nine Old Men was 61 when the movie was released. I suspect indeed that they would have retired before this point, except that with Walt gone there was the idea that some continuity had to be maintained; but they really had nothing new to say with the art form, and the chief feeling one gets from the animation in Robin Hood is one of fatigue: these were men who had worked on the most expansive, ambitious animations in American history, and now they were being asked to make a matinee picture. I don't blame them for the general stiffness that pervades the film, particularly Robin himself - only Prince John (directed by Ollie Johnston, with some input from Frank Thomas) is a particularly well-achieved bit of character animation, and I imagine that Ustinov's performance helped with that. Even the great Milt Kahl, responsible for the Sheriff, couldn't do much with the character, who is at any rate marked by a truly outrageous amount of recycled animation from scene to scene.

Boy, is there ever a problem with recycling in Robin Hood: it might have the most re-used animation of any Disney feature, especially in the "Phony King of England" scene. A healthy chunk of the "I Wanna Be Like You" dance from The Jungle Book is reworked, plus some dancing from The Aristocats; most notoriously, Marian's movements for a good 15 seconds are taken straight from Snow White herself - which has the benefit, at least, of making Marian look better in those seconds than anyone else in the whole movie. Design elements are stolen from a number of movies, some sound effects are taken from Cinderella, and that doesn't address how much of the animation is reused with the film itself. It's not laziness, it's cost-cutting, but it does certainly add to the feeling that what we're watching could just as easily have been put together by Filmation with a better background artist (I'll say this, at least: the effects animation is top notch. But the effects animation always is in a Disney film, no matter what else is wrong; and that is why I rarely mention it).

At the same time as the old guard was getting, um, old, there was some fresh blood coming in: Eric Larson, former animator and one of the Nine Old Men, quit the animation department during this film's production (he hadn't been a directing animator in some time) to head up the new training wing of the studio, finding new talent and teaching them how to do what the Disney animators in the prime did better than anyone else. These younger generations of artists had been around for a while, of course, but it was with Robin Hood that they first got to take charge. Not as directing animators, of course, but as featured character animators: among them was a man named Don Bluth, given his first on-screen credit after more than a decade with Disney; this fellow's development would be of keen importance to the studio, though not in the way the company might have liked.

The kids couldn't do much, though, for the project was hobbled by a low budget and low expectations, and when it was finally dropped into theaters, it was as a sheer commercial object, with as little artistry as anything in Disney's history - not even the bizarre psychedelia of "Ev'rybody Wants to Be a Cat" to save it. It is said that Ken Anderson was heartbroken to see what his characters had been reduced to, as well he might be.

But the film did a bit of business - more than The Aristocats, at least - and it achieved its tiny goal of delighting young audiences, and presumably adult audiences as well who were sufficiently determined to have a fun time laughing at silly critters. I would hate to deny it at least that success - it is "fun", in an unusually disposable way. More importantly, it seems to have kicked the animators into high gear, because they quickly started on the next feature project, one that would not be any kind of masterpiece, but certainly represented a better achievement on every important level: more interesting, sympathetic characters, brought to life with higher-quality animation and design. Robin Hood may have been a low ebb, but at least it was not protracted.