Disney Animation: In a fix, in a bind, call on us anytime

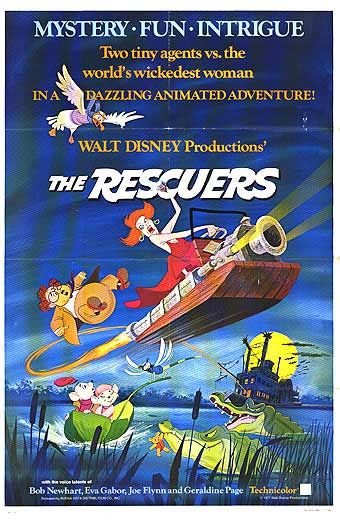

The last animated film released by Walt Disney Productions in the 1970s is a transitional work, the handing of the torch from one generation to another. Even though several of the older generation who was still around at this point managed to stick around for one last film, 1977's The Rescuers still has a valedictory feel; it's also the first work produced by several young animators trained by Eric Larson's talent farm, at least a few of whom went on to become some of the most important names at the Disney studios. By and large, the old-school animators regarded this as the first really satisfying production made by the company since Walt died, and it's frankly not too hard to agree that, the Silver Age holdover The Many Adventures of Winnie the Pooh notwithstanding, The Rescuers is probably the one completely successful feature produced between 1967 and the beginning of the Disney Renaissance in 1989. By happy accident, it seems that audiences of the time agree with me: the film enjoyed the highest first-run gross of any of the studio's films during that time period. It's not a timeless masterpiece, nor one of the all-time outstanding Disney animated features. But it more than gets the job done, something you can't necessarily say for a lot of the films made around it.

The film opens with something new for Disney: a pre-credits sequence, in which a little girl with a teddy bear creeps out onto the deck of ruined paddle steamer in the middle of a dismal swamp. Two ominous crocodilian shapes with narrow green eyes watch her throw a bottle containing a note into the water. It's a really fine way to start up a movie: we have no idea what's going on yet, but we know it's not at all comforting, and assuming we have any affection for children whatsoever, we're instantly concerned that whoever this girl is, she's in trouble. Quite a good, moody introduction to a film that proves to be more of a thriller than anything else yet produced by the studio.

When the credits start up, we are introduced to a really wonderful selection of still shots that trace the bottle's course out to see and up the coast to New York City. These are oil paintings by Melvin Shaw, made with stark, impressionistic lines, and details meant to evoke the rough texture of canvas or burlap only barely covered by paint. All told, they are as beautiful as anything else produced in the xerography age to that point, which would be enough reason for tarrying and mentioning it.

But I'd like to stay with the credits a little bit longer, because there are some people we have to say goodbye to, and some new people to greet in their stead. The first folks we come to are the film's four directing animators, three of them old veterans and one of them newly promoted from the ranks of character animators.

Ollie Johnston, Milt Kahl, and Frank Thomas are certainly three people we've come to know very well over the course of 23 features. They were the last of the Nine Old Men to work directly in the animation studio, which gives me a good chance to speak once for all about the significance of these three and their six colleagues, and what they did for the development of American animation over the course of some fifty years.

I should speak one caveat at the start: though I have certainly been guilty of doing this throughout, it's not right to give the Nine Old Men total credit for all the good animation to come out of these features. They were by and large only directing animators, especially beginning in the'50s; that is, they'd draw the key frames for an action, leaving a team of assistants (the character animators) to fill in the details of movment. With very few exceptions - and we'll be meeting one of them shortly - no character was entirely the work of a single animator.

Nor is it entirely fair to say that the Nine Old Men are without question the finest people to come out of Disney during their generation; they are not grouped together by some consensus of history, but because Walt Disney specifically chose to group them. It is probably accurate to say that they are the nine best animators that Walt liked; at the same time they were first officially named as a group, men like Vladimir "Bill" Tytla and Art Babbitt were doing work just as good, but in both cases, those animators had run afoul of the boss man personally, especially during the 1941 animators' strike. So even though they were good enough to earn the historic privilege accorded to the Nine Old Men, they were deprived of the same opportunities by a producer with an axe to grind.

All this being said, the achievement of the nine animators is not merely illusory or marketing. The really did quite a bit to define a specific strand of animation: defining and explaining theories of movement (it has to be slightly exaggerated), physical mutability (an object that "squashes and stretches" will be more appealing than one that is rigid), character interaction (Johnston's famous discovery about how emotion is generated when characters touch), facial expression, the use of the line, and the use of the space "in between" frames. There are many great animated films made according to an entirely different set of preconceptions, but for the Disney style, inarguably the most significant mode of animation in America until at least the end of the 1990s, these nine men were the experts and the lawmakers, without whose discipline, we can safely assume that the memorable characters that have been part of the Disney stable since the 1930s would not be have as charming, lovable, scary, or believable.

Johnston and Thomas weren't quite finished with the studio yet, but the time has come to bid our farewells to Milt Kahl, arguably the most technically proficient artist the studio ever employed (I'd say that Tytla gives him stiff competition; but he directed such a comparatively tiny number of characters!). His contribution to The Rescuers is its villain, the last in a long run of excellent Kahl bad guys. In this case, I refer to Medusa, voiced by Geraldine Page, a flighty, dumpy woman with a shock of red hair and an angular face, and a tendency towards over-the-top, campy movements. Allegedly, she was inspired by Kahl's hated ex-wife, and it must be said that if she is quite memorable, this is largely at the expense of being one of the most wickedly female of all Disney's lady villains (in the earliest story drafts, her role was filled by Cruella De Vil of One Hundred and One Dalmatians, an idea scrapped when it was concluded, ironically, that a sequel was a bad idea; both women share the distinction of being the most regressive depictions of insane, materialistic, narcissistic females, both of them totally incapable of driving a car properly, in the studio's canon). Kahl had such specific ideas for how she ought to be animated, that he did virtually all of the work himself, finding that his assistants weren't up to his demands; and it is quite pleasing that his farewell to Disney feature animation should not only be a solo job, but one of the most excitingly kinetic of all Disney villains. Though Medusa is ultimately too broadly comic the stand in the very top tier, she is a masterful piece of animation, with her putty-like tendency to stretch and bounce in a slightly grotesque caricature of the human form; any animator would be proud to call her his swan song.

As for Thomas and Johnston, they both did fine work in the film, allowing that Medusa is the unchallenged stand-out in the cast. Really, there are no weak characters in The Rescuers, with its two mouse protagonists both fully fleshed out and animated to best suggest their very different peronalities: the male mouse, Bernard (voiced by Bob Newhart), is twitchy and nervous and has never actually gone on a rescue mission before, and his animation is accordingly jerky and full of short, awkward movements. His partner, Bianca (voiced by Eva Gabor), is sensible, unafraid and very clever, and she moves with a fluidity and ease that reinforces that impression. Johnston himself makes something of a cameo appearance in the form of the old cat Rufus (voiced by John McIntire, one of two Psycho alumni in the cast), given a bushy Johnston-esque mustache by the young animators in tribute to their admiration for his many years of inspiring work.

The new kid on the block was Don Bluth, finally hitting the top levels after many years in the company's employ. We can, in retrospect, read some Bluth style into certain characters: many of the background mice in the Rescue Aid Society that sends Bernard and Bianca on their mission; also in Penny (Michelle Stacy), the young orphan girl who sent the bottle out into the world, a profoundly innocent little thing (she talks to her teddy bear, and treats him as her best friend) thrust into an ugly situation in a brutal plea for our sympathy that comes this close to working, about which I'll say more in a bit.

Bluth proved to be a great addition to the Disney family; he clearly understood the mentality behind the studio's greatest achievements, but had enough personality of his own that he wasn't just a cog. He was a truly gifted artist, and if history had been somewhat different, I think he might have done wonderful things with the resources Disney made available to him. But the future wasn't going to be that kind, as we shall find out in due course.

Moving further into the credits, as we hit the list of character animators, we see the first appearance of several tremendously important names that will become, in the films to come, as important to know as Ward Kimball or Marc Davis were in the past. There is John Pomeroy, who we first met in The Many Adventures of Winnie the Pooh; he was hired during production of the third segment. Brand new people include the future director Ron Clements, and Glen Keane, one of the truly vital figures of the subsequent thirty years of Disney, an animator who proved his indispensability with the very next project, but for right now simply toiled, doing what I have no doubt was his customarily excellent work.

Now we come to the producer credit: Wolfgang Reitherman is still serving in that capacity, the line connecting the past and the future, Walt's aesthetic heir apparent; but now we find an executive producer that we haven't seen before. Ron Miller was Walt's son in law, marrying Diane Disney in 1954 (they are still married, incidentally), and had spent most of the '70s overseeing the live-action arm of the film department. It was only now that the top brass moved him over to stand in charge of the animation studio as well; and the full flower of that decision was not to be felt in The Rescuers, but he'll come to be a very important man in the annals of Disney history, so remember here, where we first met him.

Lastly, we come to the film's three directors: Reitherman once more, splitting duties with two collaborators, John Lounsbery and Art Stevens. Lounsbery was of course one of the Nine Old Men, just like Woolie Reitherman; promoted out of the directing animator racket in the Winnie the Pooh years to help his colleague, for these men were getting quite old, and the responsibility for a whole feature was too much to ask. Unfortunately, Lounsbery would not enjoy his new job for long. In Februrary, 1976, he passed away, the first of the Nine Old Men to die, and the second to leave the Disney fold: Les Clark, who had long since moved into directing short films, retired just shortly before Lounsbery's death.

Stevens, a Disney animator since the 1950s, was called in as a pinch-hitter; he learned enough of the directing craft to take over for Reitherman in the next feature, despite being no spring chicken himself. Together, these two sets of two men did a fantastic job of guiding a movie that was unlike any other Disney film before it: contemporary and exciting, one of the least "fantastic", in any sense, of any feature thus far.

It's hard to say what it is, exactly, that give the film a different feeling from any of the 22 films preceding it: certainly a good place to start would be the musical score, which is pounding and distinctly electronic, and not at all the kind of flowing light-classical that the studio customarily used. The songs are another strong break: except for the anthem of the Rescue Aid Society, everything is performed by an off-screen singer, Shelby Flint: only Bambi had that same quirk to its soundtrack. The songs in The Rescuers are quite reminiscent of the singer-songwriter tradition of the 1970s (they were composed by Sammy Fain, with lyrics by Carol Conners and Ayn Robbins), and tend to date the film a bit; but they also give it a particular feeling, a sensibility that the film is not timeless but of the moment, active and living - even if its moment is more than three decades gone, at least it doesn't feel static or hermetic, like some of the very finest Disney pictures.

The Rescuers is also marked by a particular leap forward in the animation style: it was an experiment in doing new things with the xerography, using different lighter toner in the copies so that the lines didn't have to be so dramatic and black; in the case of Miss Bianca and some occasional background characters, they even used purple toner. I call it an "experiment", because it doesn't always work very soft figures occupy the same frame as much sketchier figures, and sometimes neither of them fits the background terribly well. And yet sometimes, it all comes together brilliantly, particularly in the case of the two protagonists, who are drawn like the best of the graphic, angular designs featured in the studio's films since 1961, but who also have the soothing softness of the earlier films. (Medusa, it is worth pointing out, looks a great deal like earlier "sketchy era" characters; Kahl is generally believed to be one of that aesthetic's primary boosters, as he liked the ability to translate the urgency of his drawings right onto the film without losing any of their freshness. And dammit if in this case at least, he isn't right).

The backgrounds of the film come in two quite distinct forms, and this contrast is another thing rarely or never seen in Disney. The scenes set in New York, at the beginning, have an angular, scratchy feeling akin to the backgrounds in One Hundred and One Dalmatians; there is a multiplane shot in which several rows of buildings shift about without any depth at all. The swamp is much lusher and more painterly, like what we might think of as the Disney standard. Both of them work well with the character animation, and more to the point, both are damn well set against the other: the transition from the city to the deep country is all the more dramatic because of it, and our sense of the swamp as something otherworldly is much increased as a result.

All in all, this is a fairly exciting step forward, and a comforting proof that good things could yet come out of the studio; though it is perhaps more of a promise of great things to come than a great thing itself. The story is a bit ragged, but no more so than a lot of Disney films; I don't quite understand how the world fits together, particularly why the albatross pilot Orville (Jim Jordan) makes apparently routine trips between the city and the swamp, when the swamp is obviously an isolated hellhole. It only feels particularly forced in the last ten minutes, when the waiting game of the previous half-hour erupts into the climax. But I am not completely certain that I buy all of the characters - particularly, I just don't care very much for Penny, who is so sickeningly cute and charming and precocious that I really wouldn't mind, by the end, if she happened to be eaten by those alligators. It's the one hugely obnoxious flat note in what is otherwise a tight assemblage of action movie elements, carefully re-calibrated for a young audience; but little kids in peril, be they cartoons or living beings, have a marked tendency to be too absurdly sweet for their own good, or more importantly, the audience's good. At least the villains are truly outstanding: not just Medusa, but her idiot henchman Snoops (voiced by Joe Flynn and modeled after animation historian John Culhane, who was often at the studio during the film's production), and the 'gators: they are collectively the first villains who seem like they might actually do harm to the characters since Shere Khan in The Jungle Book, and the first to marry that danger to effective comedy since the great Cruella.

If I do not love the film unreservedly, I still recognise it as a grand success for a struggling company, and in 1977, it would have seemed possible to believe, for the first time in a decade, that the Disney Studios had found an identity, sitting comfortably in the hands of a new team of animators who had the drive and the skill to keep a 40-year tradition of animated features alive. Alas that it was not to be so! This brief light of possibility and promise was quickly to be extinguished by the most terrible break in the ranks of the animation staff since the strike, set off by the launch of a project whose terrible, dispiriting, and impossibly long period of production outdid the worst of the behind-the-scenes miseries of Alice in Wonderland and Sleeping Beauty combined.

The film opens with something new for Disney: a pre-credits sequence, in which a little girl with a teddy bear creeps out onto the deck of ruined paddle steamer in the middle of a dismal swamp. Two ominous crocodilian shapes with narrow green eyes watch her throw a bottle containing a note into the water. It's a really fine way to start up a movie: we have no idea what's going on yet, but we know it's not at all comforting, and assuming we have any affection for children whatsoever, we're instantly concerned that whoever this girl is, she's in trouble. Quite a good, moody introduction to a film that proves to be more of a thriller than anything else yet produced by the studio.

When the credits start up, we are introduced to a really wonderful selection of still shots that trace the bottle's course out to see and up the coast to New York City. These are oil paintings by Melvin Shaw, made with stark, impressionistic lines, and details meant to evoke the rough texture of canvas or burlap only barely covered by paint. All told, they are as beautiful as anything else produced in the xerography age to that point, which would be enough reason for tarrying and mentioning it.

But I'd like to stay with the credits a little bit longer, because there are some people we have to say goodbye to, and some new people to greet in their stead. The first folks we come to are the film's four directing animators, three of them old veterans and one of them newly promoted from the ranks of character animators.

Ollie Johnston, Milt Kahl, and Frank Thomas are certainly three people we've come to know very well over the course of 23 features. They were the last of the Nine Old Men to work directly in the animation studio, which gives me a good chance to speak once for all about the significance of these three and their six colleagues, and what they did for the development of American animation over the course of some fifty years.

I should speak one caveat at the start: though I have certainly been guilty of doing this throughout, it's not right to give the Nine Old Men total credit for all the good animation to come out of these features. They were by and large only directing animators, especially beginning in the'50s; that is, they'd draw the key frames for an action, leaving a team of assistants (the character animators) to fill in the details of movment. With very few exceptions - and we'll be meeting one of them shortly - no character was entirely the work of a single animator.

Nor is it entirely fair to say that the Nine Old Men are without question the finest people to come out of Disney during their generation; they are not grouped together by some consensus of history, but because Walt Disney specifically chose to group them. It is probably accurate to say that they are the nine best animators that Walt liked; at the same time they were first officially named as a group, men like Vladimir "Bill" Tytla and Art Babbitt were doing work just as good, but in both cases, those animators had run afoul of the boss man personally, especially during the 1941 animators' strike. So even though they were good enough to earn the historic privilege accorded to the Nine Old Men, they were deprived of the same opportunities by a producer with an axe to grind.

All this being said, the achievement of the nine animators is not merely illusory or marketing. The really did quite a bit to define a specific strand of animation: defining and explaining theories of movement (it has to be slightly exaggerated), physical mutability (an object that "squashes and stretches" will be more appealing than one that is rigid), character interaction (Johnston's famous discovery about how emotion is generated when characters touch), facial expression, the use of the line, and the use of the space "in between" frames. There are many great animated films made according to an entirely different set of preconceptions, but for the Disney style, inarguably the most significant mode of animation in America until at least the end of the 1990s, these nine men were the experts and the lawmakers, without whose discipline, we can safely assume that the memorable characters that have been part of the Disney stable since the 1930s would not be have as charming, lovable, scary, or believable.

Johnston and Thomas weren't quite finished with the studio yet, but the time has come to bid our farewells to Milt Kahl, arguably the most technically proficient artist the studio ever employed (I'd say that Tytla gives him stiff competition; but he directed such a comparatively tiny number of characters!). His contribution to The Rescuers is its villain, the last in a long run of excellent Kahl bad guys. In this case, I refer to Medusa, voiced by Geraldine Page, a flighty, dumpy woman with a shock of red hair and an angular face, and a tendency towards over-the-top, campy movements. Allegedly, she was inspired by Kahl's hated ex-wife, and it must be said that if she is quite memorable, this is largely at the expense of being one of the most wickedly female of all Disney's lady villains (in the earliest story drafts, her role was filled by Cruella De Vil of One Hundred and One Dalmatians, an idea scrapped when it was concluded, ironically, that a sequel was a bad idea; both women share the distinction of being the most regressive depictions of insane, materialistic, narcissistic females, both of them totally incapable of driving a car properly, in the studio's canon). Kahl had such specific ideas for how she ought to be animated, that he did virtually all of the work himself, finding that his assistants weren't up to his demands; and it is quite pleasing that his farewell to Disney feature animation should not only be a solo job, but one of the most excitingly kinetic of all Disney villains. Though Medusa is ultimately too broadly comic the stand in the very top tier, she is a masterful piece of animation, with her putty-like tendency to stretch and bounce in a slightly grotesque caricature of the human form; any animator would be proud to call her his swan song.

As for Thomas and Johnston, they both did fine work in the film, allowing that Medusa is the unchallenged stand-out in the cast. Really, there are no weak characters in The Rescuers, with its two mouse protagonists both fully fleshed out and animated to best suggest their very different peronalities: the male mouse, Bernard (voiced by Bob Newhart), is twitchy and nervous and has never actually gone on a rescue mission before, and his animation is accordingly jerky and full of short, awkward movements. His partner, Bianca (voiced by Eva Gabor), is sensible, unafraid and very clever, and she moves with a fluidity and ease that reinforces that impression. Johnston himself makes something of a cameo appearance in the form of the old cat Rufus (voiced by John McIntire, one of two Psycho alumni in the cast), given a bushy Johnston-esque mustache by the young animators in tribute to their admiration for his many years of inspiring work.

The new kid on the block was Don Bluth, finally hitting the top levels after many years in the company's employ. We can, in retrospect, read some Bluth style into certain characters: many of the background mice in the Rescue Aid Society that sends Bernard and Bianca on their mission; also in Penny (Michelle Stacy), the young orphan girl who sent the bottle out into the world, a profoundly innocent little thing (she talks to her teddy bear, and treats him as her best friend) thrust into an ugly situation in a brutal plea for our sympathy that comes this close to working, about which I'll say more in a bit.

Bluth proved to be a great addition to the Disney family; he clearly understood the mentality behind the studio's greatest achievements, but had enough personality of his own that he wasn't just a cog. He was a truly gifted artist, and if history had been somewhat different, I think he might have done wonderful things with the resources Disney made available to him. But the future wasn't going to be that kind, as we shall find out in due course.

Moving further into the credits, as we hit the list of character animators, we see the first appearance of several tremendously important names that will become, in the films to come, as important to know as Ward Kimball or Marc Davis were in the past. There is John Pomeroy, who we first met in The Many Adventures of Winnie the Pooh; he was hired during production of the third segment. Brand new people include the future director Ron Clements, and Glen Keane, one of the truly vital figures of the subsequent thirty years of Disney, an animator who proved his indispensability with the very next project, but for right now simply toiled, doing what I have no doubt was his customarily excellent work.

Now we come to the producer credit: Wolfgang Reitherman is still serving in that capacity, the line connecting the past and the future, Walt's aesthetic heir apparent; but now we find an executive producer that we haven't seen before. Ron Miller was Walt's son in law, marrying Diane Disney in 1954 (they are still married, incidentally), and had spent most of the '70s overseeing the live-action arm of the film department. It was only now that the top brass moved him over to stand in charge of the animation studio as well; and the full flower of that decision was not to be felt in The Rescuers, but he'll come to be a very important man in the annals of Disney history, so remember here, where we first met him.

Lastly, we come to the film's three directors: Reitherman once more, splitting duties with two collaborators, John Lounsbery and Art Stevens. Lounsbery was of course one of the Nine Old Men, just like Woolie Reitherman; promoted out of the directing animator racket in the Winnie the Pooh years to help his colleague, for these men were getting quite old, and the responsibility for a whole feature was too much to ask. Unfortunately, Lounsbery would not enjoy his new job for long. In Februrary, 1976, he passed away, the first of the Nine Old Men to die, and the second to leave the Disney fold: Les Clark, who had long since moved into directing short films, retired just shortly before Lounsbery's death.

Stevens, a Disney animator since the 1950s, was called in as a pinch-hitter; he learned enough of the directing craft to take over for Reitherman in the next feature, despite being no spring chicken himself. Together, these two sets of two men did a fantastic job of guiding a movie that was unlike any other Disney film before it: contemporary and exciting, one of the least "fantastic", in any sense, of any feature thus far.

It's hard to say what it is, exactly, that give the film a different feeling from any of the 22 films preceding it: certainly a good place to start would be the musical score, which is pounding and distinctly electronic, and not at all the kind of flowing light-classical that the studio customarily used. The songs are another strong break: except for the anthem of the Rescue Aid Society, everything is performed by an off-screen singer, Shelby Flint: only Bambi had that same quirk to its soundtrack. The songs in The Rescuers are quite reminiscent of the singer-songwriter tradition of the 1970s (they were composed by Sammy Fain, with lyrics by Carol Conners and Ayn Robbins), and tend to date the film a bit; but they also give it a particular feeling, a sensibility that the film is not timeless but of the moment, active and living - even if its moment is more than three decades gone, at least it doesn't feel static or hermetic, like some of the very finest Disney pictures.

The Rescuers is also marked by a particular leap forward in the animation style: it was an experiment in doing new things with the xerography, using different lighter toner in the copies so that the lines didn't have to be so dramatic and black; in the case of Miss Bianca and some occasional background characters, they even used purple toner. I call it an "experiment", because it doesn't always work very soft figures occupy the same frame as much sketchier figures, and sometimes neither of them fits the background terribly well. And yet sometimes, it all comes together brilliantly, particularly in the case of the two protagonists, who are drawn like the best of the graphic, angular designs featured in the studio's films since 1961, but who also have the soothing softness of the earlier films. (Medusa, it is worth pointing out, looks a great deal like earlier "sketchy era" characters; Kahl is generally believed to be one of that aesthetic's primary boosters, as he liked the ability to translate the urgency of his drawings right onto the film without losing any of their freshness. And dammit if in this case at least, he isn't right).

The backgrounds of the film come in two quite distinct forms, and this contrast is another thing rarely or never seen in Disney. The scenes set in New York, at the beginning, have an angular, scratchy feeling akin to the backgrounds in One Hundred and One Dalmatians; there is a multiplane shot in which several rows of buildings shift about without any depth at all. The swamp is much lusher and more painterly, like what we might think of as the Disney standard. Both of them work well with the character animation, and more to the point, both are damn well set against the other: the transition from the city to the deep country is all the more dramatic because of it, and our sense of the swamp as something otherworldly is much increased as a result.

All in all, this is a fairly exciting step forward, and a comforting proof that good things could yet come out of the studio; though it is perhaps more of a promise of great things to come than a great thing itself. The story is a bit ragged, but no more so than a lot of Disney films; I don't quite understand how the world fits together, particularly why the albatross pilot Orville (Jim Jordan) makes apparently routine trips between the city and the swamp, when the swamp is obviously an isolated hellhole. It only feels particularly forced in the last ten minutes, when the waiting game of the previous half-hour erupts into the climax. But I am not completely certain that I buy all of the characters - particularly, I just don't care very much for Penny, who is so sickeningly cute and charming and precocious that I really wouldn't mind, by the end, if she happened to be eaten by those alligators. It's the one hugely obnoxious flat note in what is otherwise a tight assemblage of action movie elements, carefully re-calibrated for a young audience; but little kids in peril, be they cartoons or living beings, have a marked tendency to be too absurdly sweet for their own good, or more importantly, the audience's good. At least the villains are truly outstanding: not just Medusa, but her idiot henchman Snoops (voiced by Joe Flynn and modeled after animation historian John Culhane, who was often at the studio during the film's production), and the 'gators: they are collectively the first villains who seem like they might actually do harm to the characters since Shere Khan in The Jungle Book, and the first to marry that danger to effective comedy since the great Cruella.

If I do not love the film unreservedly, I still recognise it as a grand success for a struggling company, and in 1977, it would have seemed possible to believe, for the first time in a decade, that the Disney Studios had found an identity, sitting comfortably in the hands of a new team of animators who had the drive and the skill to keep a 40-year tradition of animated features alive. Alas that it was not to be so! This brief light of possibility and promise was quickly to be extinguished by the most terrible break in the ranks of the animation staff since the strike, set off by the launch of a project whose terrible, dispiriting, and impossibly long period of production outdid the worst of the behind-the-scenes miseries of Alice in Wonderland and Sleeping Beauty combined.