Disney Animation: For every to there is a fro

Following the success of One Hundred and One Dalmatians, Walt Disney Production's most contemporary and "hippest" film yet (though "hip" and "Disney" are correctly thought of as mortal enemies to one another), the studio immediately ran as far as possible to the other direction, making a film rooted in an antiquity that hadn't even been approached by the medieval fairy tale adaptations - in fact, there would be only two Disney features, three and a half decades later, adapted from more ancient source material.

I refer to the Arthur mythology of Britain, rooted in a legendary tradition lost to time but almost certainly dating to earlier than 1000 CE; though the best-known shape of the myth begins with Geoffrey of Monmouth's Historia Regum Britanniae from 1138, and significant portions of the legendarium were still being added by (mostly French) sources throughout the early medieval period. That the Matter of Britain would make a fine subject for a Disney animation must have been obvious long before the studio actually completed The Sword in the Stone in 1963, and I imagine that it was particularly appealing because, like Peter Pan, it presented a "masculine" narrative, rather than the more common and distinctly more feminine treatment given to classic Western fairy tales in the "princess cycle" of films. This is based upon nothing but my own suppositions about the Disney Studios' generally reductive treatment of gender roles, but one does not need to subscribe to the company's paradigm to observe that historically, they made more as it were "girl" films than as it were "boy" films - at the very least, the "girl" films have a significantly more prominent place in the company's history and box office records (of course, most of the studio's projects were quite gender-neutral, with the acknowledgment that any film made almost solely by men will naturally take on a masculine perspective; and I think this only really serves to indicate how ultimately irritating it is to try and view everything in gender-theoretical terms).

The Arthur myth is of course a matter of great seriousness and sobriety, and as I have hopefully argued convincingly in regards to One Hundred and One Dalmatians, seriousness and sobriety were two qualities not well-served by the animation style Disney was forced to adopt in the early 1960s. A convincingly epic retelling of the Arthur legend would frankly have looked stupid were it rendered in the scratchy, graphic aesthetic that the new xerography technology demanded.

Here is where even sheer speculation comes grinding to a halt, and I now continue in what can only be considered a spirit of idle curiosity. Unlike many of Disney's features before and after, I know nothing of how The Sword in the Stone came to be developed as a story; of its history I can say not even say with certainty when it entered animation, although the last quarter of 1960, when the finishing touches were just being put on One Hundred and One Dalmatians, seems to be likely, giving the film a comfortable 2.5 year production.

So I cannot say, though the question deeply interests me, of whether the idea first came up to do a feature adaptation of the Arthur legend, and T.H. White's 1938 novel The Sword in the Stone was selected on the basis that it provided a suitably comic revision of what had been, to Thomas Malory, a perfectly humorless work indeed; or whether Arthur hadn't indeed cropped up at the studio at all until somebody chanced to read the novel and saw in it a likely candidate for future canonisation. I have found one reference that, in 1944, it was announced that Disney had acquired The Ill-Made Knight, the second sequel (published in 1940) to White's first Arthur novel, although I do not feel quite comfortable trusting this nugget. At any rate, by the time The Sword in the Stone: The Movie entered production, White had anthologised and revised his three novels and added a fourth, combining the whole package into a thick 1958 text called The Once and Future King, and the closeness of that date to the active development of Disney's film makes it impossible for me to believe that the latter event wasn't influenced - even spurred on - by the former. But as I said, which element of all this came first, and why, is something that I am entirely unable to say. All I know is that White provided a very convenient version of the Arthur story that hardly could have been better-tailored for Disney's needs in the early 1980s: it treats heavily upon the king's boyhood, it is broadly comic, and much of the humor is pointedly modern, thanks to White's innovation of suggesting that the great wizard Merlin was born far in the future and is aging backwards through time, leading especially in the first book of the tetralogy to a great many anachronistic gags that story man Bill Peet (once again working totally solo) was perfectly eager to bring into his version of the story.

This was the only possible way that Disney could have made this film in this period: it is not exactly a modern dress version of King Arthur, but rather a modern attitude version, with vernacular and gags that are based on the contrast between the 20th Century and whatever ill-defined period the film takes place in - Merlin often refers to it as the Middle Ages, which in British history usually denotes the period after the Norman Conquest of 1066 CE, although Merlin also claims that the London Times won't start publication for more than 1200 years, setting the story in the late-6th Century. Upon reflection, this is not an issue of particular importance. What I was first trying to say is that this is a peculiarly ironic and modern take on the Matter of Britain, and ideally suited for the scratchy aesthetic of 1963.

White's novel and Disney's film were produced for two different audiences in two entirely different contexts (the book can only be read as a work of anxiety presaging what was in 1937 and '38 looking to be an inevitable war with Germany's Third Reich; the film was made for kids at a period when American influence and optimism was at its all-time peak), and it is hardly shocking that they are thus rather different beasts, but it's surprising, to me anyway, to observe how well the Disney version tracks the spirit of the novel, if not its specific incident (it is not at all unusual for Disney adaptations of particular works of literature to do neither of these things). Obviously, it's not an improvement on the source material, nor even its equal in another medium; but every time I re-watch it, I find that I like it more than I remember, and frankly more than I think I have any right to. As far as Silver Age Disney features go, The Sword in the Stone is probably the most obscure these days, and no one could objectively call that a crime against art history (whereas, for example, I am constantly distressed at how few people apparently have seen The Three Caballeros). But it is nevertheless a fun movie, with good animation, and it represents a significant refinement in the xerography technology of One Hundred and One Dalmatians, a far bigger jump indeed that I would have imagined likely in the span of just one film, and it makes a good effort at being something like My First Arthur Story - which it was for this particular Arthuriana buff, if nobody else.

The broadest strokes of the story are basically the same in both version: the foundling Arthur, nicknamed the Wart by those around him, meets with the great wizard Merlin one day, and Merlin - knowing that Arthur has quite a profound future in front of him - takes it upon himself to become the boy's tutor. This tutelage includes not only important subjects like reading and mathematics, but a social sciences curriculum like never otherwise seen on this earth: for Merlin takes to transforming the Wart into a variety of animals, and the things the boy learns by observing the world in this form give him an understanding of abstruse moral and philosophical issues that will one day serve to make him a more gentle and wiser king; an event that happens at the very end, when the Wart quit accidentally and in total naïveté pulls a sword from an anvil upon a stone and proves himself the proper heir to the late King Uther Pendragon. I cannot quite say why Peet made some of the particular changes he did to the subject matter: that Merlin is now a time-traveler and not living backwards through history was probably done to keep such an esoteric concept from blowing up the children's minds in the audience, but I have never particularly understood why it made sense to turn Kay from the Wart's best friend and near-contemporary to a smug, monotone bully with fully ten years on the preteen hero. These are of course fairly minimal concerns.

The film itself boasts a blend of thoughtfulness and silliness that remains fairly exceptional in the Disney canon. None of the studio's other work is so forthright about raising a number of philosophical considerations, in a family-friendly way of course; much less intellectually rigorous than the book, to a dead certainty. At the same time, it does not present its issues with the "here is a Lesson" flatness of an Aesop fable, like so many of its other animated features. I might put it a different way: most Disney films have a single message, raised in the first act, largely ignored by the entertaining second act, and hammered home in the third act: "Growing up is not a terrible thing" in Peter Pan, "Don't judge a book by its cover" in Beauty and the Beast, "Never give up on your dreams" in damn near all of the rest. The Sword in the Stone doesn't present a message so much as a system of thinking, which is developed piece by piece in each of the film's three major sequences - the story follows, I think, a five-act structure, found nowhere else in Disney: a prelude, the three parts in the middle, each with their own system of conflict, and an epilogue. In this, it surely counts as one of the most interesting narrative systems of any film the studio ever produced.

At the same time, the themes of the film are undoubtedly of secondary importance to its humor; this is only the second Disney film that is first and foremost a comedy, which is an observation I shall hereafter cease making; it is true of every film made at Disney in the '60s and '70s that it is first a comedy, for which I can only feebly point to the xerography revolution and its attendant graphic simplicity as the likeliest cause. Now, the comedy is sot so effective here, I think, as in One Hundred and One Dalmatians, which is of course largely a matter of taste, and if I am inclined to agree with The Sword in the Stone's faintly hidden place in Disney history, this would be a primary reason. Some of the jokes are tremendously effective, mostly the ones that primarily involve Merlin's rather distracted perspective of life in the First Millennium. In this the film owes a huge debt to TV character actor Karl Swenson, whose voice performance (his only one for Disney) is an impeccable example of comic timing and inflection. And some of the jokes are just sort of there, and this includes virtually all of the film's physical humor, which is a significant step down from the previous film, which had three excellent comic villains upon which to rain its slapstick.

Besides its gag-heavy plotting, the best way that the film promotes its overall lightness of tone is through its songs, and a more jingly collection of hummable, fun numbers had never been seen in a Disney film. For this, we must thank the brothers Robert and Richard Sherman, Tin Pan Alley songwriters whose first work for the studio (probably written about the same time as their Sword in the Stone work) was the live-action The Parent Trap, in 1961; it would take no time at all until they had become one of the most important creative forces in Disney history, writing the songs for three of the next five animated features, as well as the sublimely iconic soundtrack to the 1964 masterpiece Mary Poppins. They also wrote one of the most notorious earworms in the history of song, the theme to the Disney theme park ride it's a small world.

But let's not skip ahead. For right now, they contributed five songs to The Sword in the Stone, and the barely-heard scraps of a sixth; discounting the drowsy opening tune as a necessary bit of scene-setting, what remains is a marvelous mix of playful numbers that are all irritatingly memorable (for this is the hallmark of the Sherman Brothers' songs), and which combine with each other in quite effective ways. The two songs which Merlin sings to the Wart during his animalistic sojourns, "That's What Makes the World Go Round" and "A Most Befuddling Thing" make a rather effective pair, and combine to express the sometimes weighty concepts explored in the film with sprightly efficiency:

We also have Merlin's nonsense song "Higitus Pigitus, an early example of what would become an important element of the 1990s films, the Big Ol' Showstopper number in which a lot of crazy things happen accompanied by a particularly high-tempo song, and "Mad Madam Mim", which is just a fun little comic number for the villain. All in all, it's one of the best scores to any Disney film in the Silver Age: it lacks a flat-out masterpiece like "Bibbidi-Bobbidi-Boo" or "You Can Fly", but it also lacks any outright clinkers, like "So This Is Love" or "Your Mother and Mine".

The downside to all this playfulness is that the film is plagued by shallowness, the second primary flaw with the movie. Of particular concern is the third segment, in which the Wart becomes a squirrel and learns about implacable forces, like gravity and love, and breaks the heart of a pretty girl squirrel in the process. There is no more jarring transition in the film than that from Merlin's sad observation that love is one of the most powerful things in the universe, as we in the audience watch the squirrel descend into mourning for her lost love, to the comic disaster of Merlin's kitchen-cleaning spell. It's like on the local news, when the anchor goes from talking about the teenager who was murdered to the tap-dancing pig without missing a beat. And it happens semi-frequently; not so drastically, but the film is distinctly anxious to keep real emotions out when they threaten the integrity of the comedy.

My God, I still haven't more than mentioned the animation. Well, like I said, the xerography is a great deal more refined here than it was in One Hundred and One Dalmatians; there are virtually none of the ghostly pencil marks found so frequently in that movie, although they do have a tendency to appear rather frequently around characters' hairlines. Beyond that, The Sword in the Stone finds the animators much more comfortable, on the whole, with the angular aesthetic they had now been saddled with, and so the overall look of the movie seems to more of a single piece than it did in the last film, where Cruella De Vil especially tended to overwhelm everything else on screen. Which may well be just another way of saying that none of the design The Sword in the Stone is as singularly memorable as Cruella, and I will not seek to correct anybody who wanted to make that argument.

(In this context, it would to mention that Wolfgang Reitherman was the solitary director of the film, something we have seen before; but this was the first film to be made without sequence directors also. Meaning that Reitherman was more singularly responsible for this film than any Disney director before him).

One of the primary differences between the two films, as far as the look of the thing is concerned, is most of the characters in The Sword and the Stone are humans. In Dalmatians, nearly every important person was a dog or other four-legged beastie, and the human beings we saw most regularly were caricatured villains. The dogs owners are seen only briefly, and make no kind of real impression. Here, though, we have characters ranging from the totally sympathetic to the villainous, all of them meant to look much as you or I do, and the results are not uniformly successful - the third primary flaw. Of particular concern is the Wart himself, who is frankly one of the less appealing protagonists anywhere in Disney. Partially, this is due to the accident of the film's production that, thanks to the speed with which 12-year-old boys' voices change, it took three actors to portray the character: Reitherman's two sons Richard and Robert, and Rickie Sorensen. Fortunately, the three boys sound passably like each other, but they were not all navigating puberty at the same rate, and so, in addition to modest but noticeable fluctuations in the Wart's voice, there are also a great many places where his voice cracks and squeals unpleasantly. But that's not the half of it.

I have never been able to figure out exactly who was the directing animator for the Wart, but that person hasn't much to be very proud of. As long as he's just standing there, it's fine: Bill Peets character designs for this movie are a fine example of the graphic style, and Arthur set a look for young Disney males that would last into the 1980s: particularly in the nose and the gangly limbs. He's awkward when he moves, but in an appealingly innocent way. And then, there are his facial expressions. There is something awful about his face, especially when he's shocked - everything stretches weirdly, and his eyes become great blank discs, and he is quite unaccountably horrible to look at. It is a rare thing to find an animated character mugging, but this is exactly what we find in the Wart: he gives the performance that you'd expect an amateur preteen to give in the same scenario in live-action, except that every motion of his body was selected by trained animators. It is absolutely fair to say that the Wart contains some of my least-favorite animation of any major character in a Disney film up to this point: not exclusively, maybe only a total of five minutes of the whole. But they are five minutes that dominate.

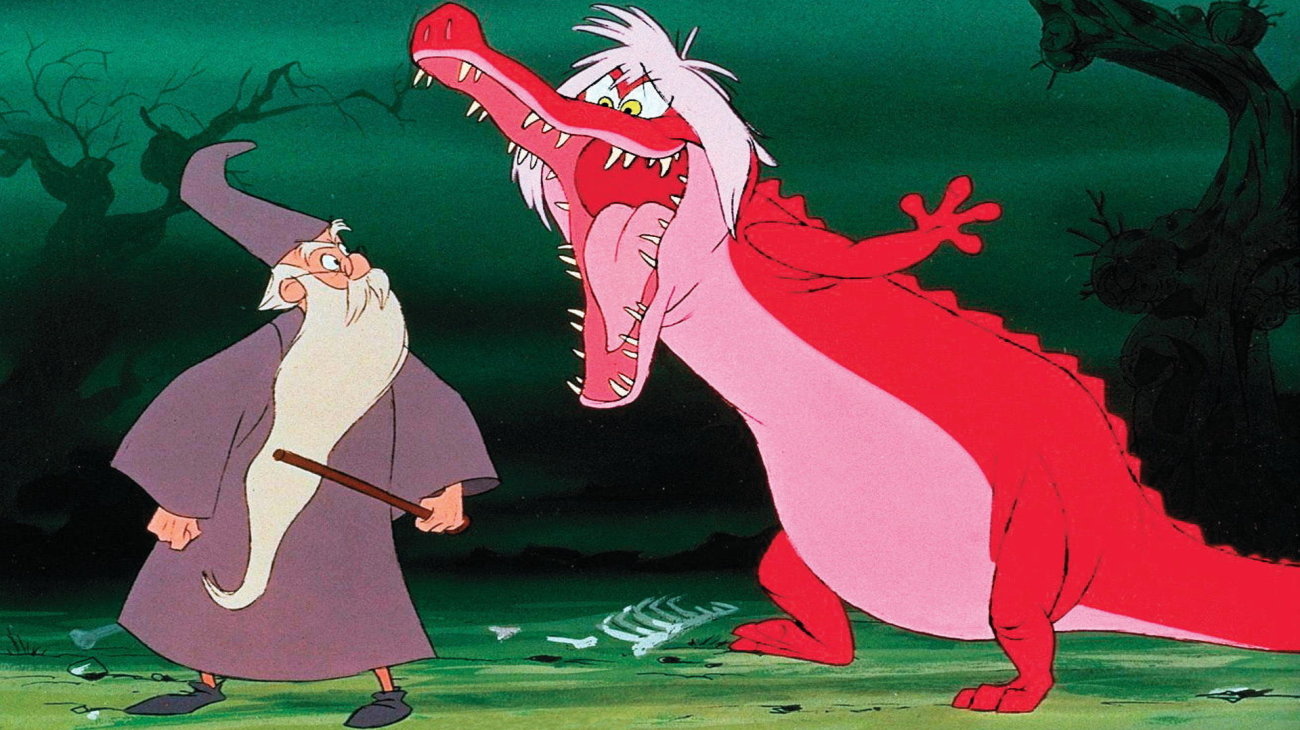

180º away from the Wart, the film also boasts one of the most technically perfect sequences ever animated, the wizard's duel between Merlin and Madam Mim, the comic villain brought in for virtually no other reason than to facilitate this great piece of character animation, executed primarily by Milt Kahl and Frank Thomas. The content of the duel couldn't be simpler: the two sorcerers turn into one animal after another, hoping to create a form that the other cannot defeat. But the execution is the finest work done by the Disney Studios in the 1960s. At its most basic, this is a tremendously effective example of personality animation: no matter what form either character transforms into, it also looks, instantly, like that character did as a human (that they are color-coded, blue and pink/purple, helps; but it is not the only thing going on here). At the same time, they never look like a human version of whatever animal they have taken on. That alone would make it an impressive sequence: but the choreography of the action, and even some of the little details of what we see (Mim's gradual fading-in as a crocodile is my favorite bit of animation in the film) are all examples of what the Disney animators could achieve when they were at their most inspired. It is often the case that a Disney cartoon will not bend reality as much as animation might; that they are so concerned with replicating reality, the animators sometimes only depict things that could be filmed in live-action, given a sufficient amount of time to train animals or design effects. But sometimes, they did something that had to, of its nature, be presented as a cartoon, and this wizard's duel - all of the "magical" sequences in film, in fact, but this one most of all - is a prime example of that.

As far as the rest of the designs go, the backgrounds are a good deal more textured and "painted" than the sketchy line drawings which mostly served as the backgrounds in One Hundred and One Dalmatians, and I must admit, for this I am grateful: those designs worked in that film, but as a new discipline I think it would have been intolerable. At the same time, they are much simpler than anything from the 1950s, to say nothing of the Golden Age: a simple color palette, little if any extraneous detail. It matches to the style of the character design well (Sleeping Beauty-like backgrounds would have been horrible here), but it still all points to the same direction as the last film: cheaper style, simpler animation, a less artsy inclination for a younger audience.

The film was a success; yet another Disney animated feature in the year-end top 10 box office hits. It was not as much of a hit with critics, who were perhaps beginning to spot Disney's new retreat into juvenilia; the film was attacked for its thin characters and over-reliance on jokes. That's an excessive reaction, because it's awfully charming and entertaining despite those things, and this reading ignores that it still has some very deep thoughts in between the laughter. But maybe I am just giving it credit for being better than the mediocrity waiting so very near into the future.

But even so, the film spoke to the continuing vitality of the company, as a business if not necessarily as an artistic powerhouse. And it was to be the final animated feature released under the Disney name while Walt Disney himself was still alive.

I refer to the Arthur mythology of Britain, rooted in a legendary tradition lost to time but almost certainly dating to earlier than 1000 CE; though the best-known shape of the myth begins with Geoffrey of Monmouth's Historia Regum Britanniae from 1138, and significant portions of the legendarium were still being added by (mostly French) sources throughout the early medieval period. That the Matter of Britain would make a fine subject for a Disney animation must have been obvious long before the studio actually completed The Sword in the Stone in 1963, and I imagine that it was particularly appealing because, like Peter Pan, it presented a "masculine" narrative, rather than the more common and distinctly more feminine treatment given to classic Western fairy tales in the "princess cycle" of films. This is based upon nothing but my own suppositions about the Disney Studios' generally reductive treatment of gender roles, but one does not need to subscribe to the company's paradigm to observe that historically, they made more as it were "girl" films than as it were "boy" films - at the very least, the "girl" films have a significantly more prominent place in the company's history and box office records (of course, most of the studio's projects were quite gender-neutral, with the acknowledgment that any film made almost solely by men will naturally take on a masculine perspective; and I think this only really serves to indicate how ultimately irritating it is to try and view everything in gender-theoretical terms).

The Arthur myth is of course a matter of great seriousness and sobriety, and as I have hopefully argued convincingly in regards to One Hundred and One Dalmatians, seriousness and sobriety were two qualities not well-served by the animation style Disney was forced to adopt in the early 1960s. A convincingly epic retelling of the Arthur legend would frankly have looked stupid were it rendered in the scratchy, graphic aesthetic that the new xerography technology demanded.

Here is where even sheer speculation comes grinding to a halt, and I now continue in what can only be considered a spirit of idle curiosity. Unlike many of Disney's features before and after, I know nothing of how The Sword in the Stone came to be developed as a story; of its history I can say not even say with certainty when it entered animation, although the last quarter of 1960, when the finishing touches were just being put on One Hundred and One Dalmatians, seems to be likely, giving the film a comfortable 2.5 year production.

So I cannot say, though the question deeply interests me, of whether the idea first came up to do a feature adaptation of the Arthur legend, and T.H. White's 1938 novel The Sword in the Stone was selected on the basis that it provided a suitably comic revision of what had been, to Thomas Malory, a perfectly humorless work indeed; or whether Arthur hadn't indeed cropped up at the studio at all until somebody chanced to read the novel and saw in it a likely candidate for future canonisation. I have found one reference that, in 1944, it was announced that Disney had acquired The Ill-Made Knight, the second sequel (published in 1940) to White's first Arthur novel, although I do not feel quite comfortable trusting this nugget. At any rate, by the time The Sword in the Stone: The Movie entered production, White had anthologised and revised his three novels and added a fourth, combining the whole package into a thick 1958 text called The Once and Future King, and the closeness of that date to the active development of Disney's film makes it impossible for me to believe that the latter event wasn't influenced - even spurred on - by the former. But as I said, which element of all this came first, and why, is something that I am entirely unable to say. All I know is that White provided a very convenient version of the Arthur story that hardly could have been better-tailored for Disney's needs in the early 1980s: it treats heavily upon the king's boyhood, it is broadly comic, and much of the humor is pointedly modern, thanks to White's innovation of suggesting that the great wizard Merlin was born far in the future and is aging backwards through time, leading especially in the first book of the tetralogy to a great many anachronistic gags that story man Bill Peet (once again working totally solo) was perfectly eager to bring into his version of the story.

This was the only possible way that Disney could have made this film in this period: it is not exactly a modern dress version of King Arthur, but rather a modern attitude version, with vernacular and gags that are based on the contrast between the 20th Century and whatever ill-defined period the film takes place in - Merlin often refers to it as the Middle Ages, which in British history usually denotes the period after the Norman Conquest of 1066 CE, although Merlin also claims that the London Times won't start publication for more than 1200 years, setting the story in the late-6th Century. Upon reflection, this is not an issue of particular importance. What I was first trying to say is that this is a peculiarly ironic and modern take on the Matter of Britain, and ideally suited for the scratchy aesthetic of 1963.

White's novel and Disney's film were produced for two different audiences in two entirely different contexts (the book can only be read as a work of anxiety presaging what was in 1937 and '38 looking to be an inevitable war with Germany's Third Reich; the film was made for kids at a period when American influence and optimism was at its all-time peak), and it is hardly shocking that they are thus rather different beasts, but it's surprising, to me anyway, to observe how well the Disney version tracks the spirit of the novel, if not its specific incident (it is not at all unusual for Disney adaptations of particular works of literature to do neither of these things). Obviously, it's not an improvement on the source material, nor even its equal in another medium; but every time I re-watch it, I find that I like it more than I remember, and frankly more than I think I have any right to. As far as Silver Age Disney features go, The Sword in the Stone is probably the most obscure these days, and no one could objectively call that a crime against art history (whereas, for example, I am constantly distressed at how few people apparently have seen The Three Caballeros). But it is nevertheless a fun movie, with good animation, and it represents a significant refinement in the xerography technology of One Hundred and One Dalmatians, a far bigger jump indeed that I would have imagined likely in the span of just one film, and it makes a good effort at being something like My First Arthur Story - which it was for this particular Arthuriana buff, if nobody else.

The broadest strokes of the story are basically the same in both version: the foundling Arthur, nicknamed the Wart by those around him, meets with the great wizard Merlin one day, and Merlin - knowing that Arthur has quite a profound future in front of him - takes it upon himself to become the boy's tutor. This tutelage includes not only important subjects like reading and mathematics, but a social sciences curriculum like never otherwise seen on this earth: for Merlin takes to transforming the Wart into a variety of animals, and the things the boy learns by observing the world in this form give him an understanding of abstruse moral and philosophical issues that will one day serve to make him a more gentle and wiser king; an event that happens at the very end, when the Wart quit accidentally and in total naïveté pulls a sword from an anvil upon a stone and proves himself the proper heir to the late King Uther Pendragon. I cannot quite say why Peet made some of the particular changes he did to the subject matter: that Merlin is now a time-traveler and not living backwards through history was probably done to keep such an esoteric concept from blowing up the children's minds in the audience, but I have never particularly understood why it made sense to turn Kay from the Wart's best friend and near-contemporary to a smug, monotone bully with fully ten years on the preteen hero. These are of course fairly minimal concerns.

The film itself boasts a blend of thoughtfulness and silliness that remains fairly exceptional in the Disney canon. None of the studio's other work is so forthright about raising a number of philosophical considerations, in a family-friendly way of course; much less intellectually rigorous than the book, to a dead certainty. At the same time, it does not present its issues with the "here is a Lesson" flatness of an Aesop fable, like so many of its other animated features. I might put it a different way: most Disney films have a single message, raised in the first act, largely ignored by the entertaining second act, and hammered home in the third act: "Growing up is not a terrible thing" in Peter Pan, "Don't judge a book by its cover" in Beauty and the Beast, "Never give up on your dreams" in damn near all of the rest. The Sword in the Stone doesn't present a message so much as a system of thinking, which is developed piece by piece in each of the film's three major sequences - the story follows, I think, a five-act structure, found nowhere else in Disney: a prelude, the three parts in the middle, each with their own system of conflict, and an epilogue. In this, it surely counts as one of the most interesting narrative systems of any film the studio ever produced.

At the same time, the themes of the film are undoubtedly of secondary importance to its humor; this is only the second Disney film that is first and foremost a comedy, which is an observation I shall hereafter cease making; it is true of every film made at Disney in the '60s and '70s that it is first a comedy, for which I can only feebly point to the xerography revolution and its attendant graphic simplicity as the likeliest cause. Now, the comedy is sot so effective here, I think, as in One Hundred and One Dalmatians, which is of course largely a matter of taste, and if I am inclined to agree with The Sword in the Stone's faintly hidden place in Disney history, this would be a primary reason. Some of the jokes are tremendously effective, mostly the ones that primarily involve Merlin's rather distracted perspective of life in the First Millennium. In this the film owes a huge debt to TV character actor Karl Swenson, whose voice performance (his only one for Disney) is an impeccable example of comic timing and inflection. And some of the jokes are just sort of there, and this includes virtually all of the film's physical humor, which is a significant step down from the previous film, which had three excellent comic villains upon which to rain its slapstick.

Besides its gag-heavy plotting, the best way that the film promotes its overall lightness of tone is through its songs, and a more jingly collection of hummable, fun numbers had never been seen in a Disney film. For this, we must thank the brothers Robert and Richard Sherman, Tin Pan Alley songwriters whose first work for the studio (probably written about the same time as their Sword in the Stone work) was the live-action The Parent Trap, in 1961; it would take no time at all until they had become one of the most important creative forces in Disney history, writing the songs for three of the next five animated features, as well as the sublimely iconic soundtrack to the 1964 masterpiece Mary Poppins. They also wrote one of the most notorious earworms in the history of song, the theme to the Disney theme park ride it's a small world.

But let's not skip ahead. For right now, they contributed five songs to The Sword in the Stone, and the barely-heard scraps of a sixth; discounting the drowsy opening tune as a necessary bit of scene-setting, what remains is a marvelous mix of playful numbers that are all irritatingly memorable (for this is the hallmark of the Sherman Brothers' songs), and which combine with each other in quite effective ways. The two songs which Merlin sings to the Wart during his animalistic sojourns, "That's What Makes the World Go Round" and "A Most Befuddling Thing" make a rather effective pair, and combine to express the sometimes weighty concepts explored in the film with sprightly efficiency:

It's up to you how far you go

If you don't try you'll never know

And so my lad as I've explained

Nothing ventured, nothing gained.

We also have Merlin's nonsense song "Higitus Pigitus, an early example of what would become an important element of the 1990s films, the Big Ol' Showstopper number in which a lot of crazy things happen accompanied by a particularly high-tempo song, and "Mad Madam Mim", which is just a fun little comic number for the villain. All in all, it's one of the best scores to any Disney film in the Silver Age: it lacks a flat-out masterpiece like "Bibbidi-Bobbidi-Boo" or "You Can Fly", but it also lacks any outright clinkers, like "So This Is Love" or "Your Mother and Mine".

The downside to all this playfulness is that the film is plagued by shallowness, the second primary flaw with the movie. Of particular concern is the third segment, in which the Wart becomes a squirrel and learns about implacable forces, like gravity and love, and breaks the heart of a pretty girl squirrel in the process. There is no more jarring transition in the film than that from Merlin's sad observation that love is one of the most powerful things in the universe, as we in the audience watch the squirrel descend into mourning for her lost love, to the comic disaster of Merlin's kitchen-cleaning spell. It's like on the local news, when the anchor goes from talking about the teenager who was murdered to the tap-dancing pig without missing a beat. And it happens semi-frequently; not so drastically, but the film is distinctly anxious to keep real emotions out when they threaten the integrity of the comedy.

My God, I still haven't more than mentioned the animation. Well, like I said, the xerography is a great deal more refined here than it was in One Hundred and One Dalmatians; there are virtually none of the ghostly pencil marks found so frequently in that movie, although they do have a tendency to appear rather frequently around characters' hairlines. Beyond that, The Sword in the Stone finds the animators much more comfortable, on the whole, with the angular aesthetic they had now been saddled with, and so the overall look of the movie seems to more of a single piece than it did in the last film, where Cruella De Vil especially tended to overwhelm everything else on screen. Which may well be just another way of saying that none of the design The Sword in the Stone is as singularly memorable as Cruella, and I will not seek to correct anybody who wanted to make that argument.

(In this context, it would to mention that Wolfgang Reitherman was the solitary director of the film, something we have seen before; but this was the first film to be made without sequence directors also. Meaning that Reitherman was more singularly responsible for this film than any Disney director before him).

One of the primary differences between the two films, as far as the look of the thing is concerned, is most of the characters in The Sword and the Stone are humans. In Dalmatians, nearly every important person was a dog or other four-legged beastie, and the human beings we saw most regularly were caricatured villains. The dogs owners are seen only briefly, and make no kind of real impression. Here, though, we have characters ranging from the totally sympathetic to the villainous, all of them meant to look much as you or I do, and the results are not uniformly successful - the third primary flaw. Of particular concern is the Wart himself, who is frankly one of the less appealing protagonists anywhere in Disney. Partially, this is due to the accident of the film's production that, thanks to the speed with which 12-year-old boys' voices change, it took three actors to portray the character: Reitherman's two sons Richard and Robert, and Rickie Sorensen. Fortunately, the three boys sound passably like each other, but they were not all navigating puberty at the same rate, and so, in addition to modest but noticeable fluctuations in the Wart's voice, there are also a great many places where his voice cracks and squeals unpleasantly. But that's not the half of it.

I have never been able to figure out exactly who was the directing animator for the Wart, but that person hasn't much to be very proud of. As long as he's just standing there, it's fine: Bill Peets character designs for this movie are a fine example of the graphic style, and Arthur set a look for young Disney males that would last into the 1980s: particularly in the nose and the gangly limbs. He's awkward when he moves, but in an appealingly innocent way. And then, there are his facial expressions. There is something awful about his face, especially when he's shocked - everything stretches weirdly, and his eyes become great blank discs, and he is quite unaccountably horrible to look at. It is a rare thing to find an animated character mugging, but this is exactly what we find in the Wart: he gives the performance that you'd expect an amateur preteen to give in the same scenario in live-action, except that every motion of his body was selected by trained animators. It is absolutely fair to say that the Wart contains some of my least-favorite animation of any major character in a Disney film up to this point: not exclusively, maybe only a total of five minutes of the whole. But they are five minutes that dominate.

180º away from the Wart, the film also boasts one of the most technically perfect sequences ever animated, the wizard's duel between Merlin and Madam Mim, the comic villain brought in for virtually no other reason than to facilitate this great piece of character animation, executed primarily by Milt Kahl and Frank Thomas. The content of the duel couldn't be simpler: the two sorcerers turn into one animal after another, hoping to create a form that the other cannot defeat. But the execution is the finest work done by the Disney Studios in the 1960s. At its most basic, this is a tremendously effective example of personality animation: no matter what form either character transforms into, it also looks, instantly, like that character did as a human (that they are color-coded, blue and pink/purple, helps; but it is not the only thing going on here). At the same time, they never look like a human version of whatever animal they have taken on. That alone would make it an impressive sequence: but the choreography of the action, and even some of the little details of what we see (Mim's gradual fading-in as a crocodile is my favorite bit of animation in the film) are all examples of what the Disney animators could achieve when they were at their most inspired. It is often the case that a Disney cartoon will not bend reality as much as animation might; that they are so concerned with replicating reality, the animators sometimes only depict things that could be filmed in live-action, given a sufficient amount of time to train animals or design effects. But sometimes, they did something that had to, of its nature, be presented as a cartoon, and this wizard's duel - all of the "magical" sequences in film, in fact, but this one most of all - is a prime example of that.

As far as the rest of the designs go, the backgrounds are a good deal more textured and "painted" than the sketchy line drawings which mostly served as the backgrounds in One Hundred and One Dalmatians, and I must admit, for this I am grateful: those designs worked in that film, but as a new discipline I think it would have been intolerable. At the same time, they are much simpler than anything from the 1950s, to say nothing of the Golden Age: a simple color palette, little if any extraneous detail. It matches to the style of the character design well (Sleeping Beauty-like backgrounds would have been horrible here), but it still all points to the same direction as the last film: cheaper style, simpler animation, a less artsy inclination for a younger audience.

The film was a success; yet another Disney animated feature in the year-end top 10 box office hits. It was not as much of a hit with critics, who were perhaps beginning to spot Disney's new retreat into juvenilia; the film was attacked for its thin characters and over-reliance on jokes. That's an excessive reaction, because it's awfully charming and entertaining despite those things, and this reading ignores that it still has some very deep thoughts in between the laughter. But maybe I am just giving it credit for being better than the mediocrity waiting so very near into the future.

But even so, the film spoke to the continuing vitality of the company, as a business if not necessarily as an artistic powerhouse. And it was to be the final animated feature released under the Disney name while Walt Disney himself was still alive.