Cloudy symbols of a high roamnce

It has been six years since Jane Campion directed her last feature film, and seven years before that since her last period drama. But you'd never be able to tell from her new Bright Star, a magnificent love story which finds the writer-director in peak condition, making what will doubtlessly be hailed as her best feature since the career-defining The Piano back in 1993 (for those of us who actually admire The Portrait of a Lady, Holy Smoke and In the Cut, things aren't so straightforward as that, but people who admire any of those films, let alone all three, are thin on the ground).

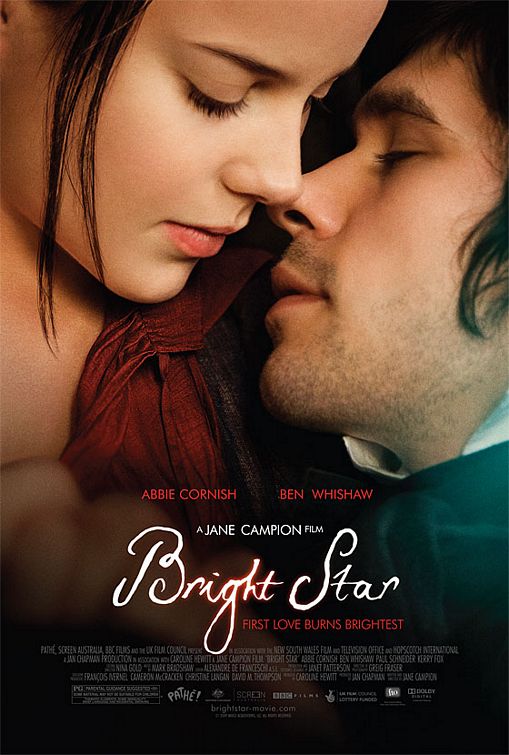

Bright Star is a truncated version of the real-life story of English Romantic poet John Keats (Ben Whishaw), and Fanny Brawne (Abbie Cornish), the young woman that he met in the last years of his life, and with whom he shared a passionate love affair that was cut short by Keats's death in 1821 of tuberculosis, at the slight age of 25. It is not to be understood that it is therefore a biopic. For most filmmakers, this would be a story about Keats the great poet, reaching his greatest heights of inspiration from the overwhelming power of love (including the composition of a famous sonnet that gives the film its title in the opening line, "Bright star! would I were steadfast as thou art"). In Campion's hands, though, Keats not only fails to be the protagonist (though he certainly counts as a co-lead, the films is clearly "about" Fanny), nothing within the movie requires that we the audience know him to be a great man of British literature; indeed, it could function just as well if Keats had been lost to history, or if he was an invented figure altogether. Insofar as the poet's later fame informs Bright Star whatsoever, it's only in that the story of the two lovers only came to prominence because Keats later became famous, and thus Campion was able to use their real-life relationship as the springboard for her movie.

And what a movie! It's a love story like they don't make any more, except I'm not certain that they ever really did. That is the whole entire theme of this film: only Brokeback Mountain in recent English-language cinema has been so completely and solely about the act of romance. But even that film - which I adore - is fairly simple in its approach to the classical love story model (make one of the men a woman, and it becomes a very well-mounted but totally straightforward drama). For Campion, a great experimental filmmaker whose experiments have yet to be fully appreciated by a critical establishment that is largely content to ignore everything she made before and after The Piano, the reason to tell a love story involving a poet is so you can make a cinematic poem; and Bright Star indeed fails to do any of the things we might expect of a costume drama romance, in favor of creating a mood that is love, rendered in a manner more poetical than narrative.

Campion has Keats himself provide the key to the movie, in a lesson on poetics to Fanny that I would love to have memorised: the thrust is that when you are in a lake, the purpose is not to analyse what about it is "lakey", but to feel and experience and understand the sensation of being in a lake; that is poetry. You do not break a poem down into its constituent atoms and hold it under a microscope, but you let the poem surround you and fill you with its emotion directly and without mediation. (He perhaps echoes Emily Dickinson's letters: "If I feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that is poetry"). Thus with Bright Star, which very nearly fails to tell a story at all: like most of Campion's films, almost as much effort is put into keeping information from the audience as to providing it. The primary example in the present film comes almost at the moment it starts, when Fanny seems smitten with Keats so instantly that we can't help but wonder why; certainly nothing he's said or done, although to be fair, looking like Ben Whishaw is a fairly compelling reason.

These narrative ellipses (and though I named the one example, the film is dense with them, particularly as regards the passage of time) are unsatisfying in e.g. a biopic, but they are sensible and necessary if the point of the film is simply to present variations over the course of two hours on an emotional state; and that is, without a doubt, the point of Bright Star. It is Jane Campion's poem on being in love, with its ups and downs and exhaustions and exhilarations. And a most beautifully executed poem it is. In Cornish and Whishaw, the director has taken two pretty, vacant young actors who (to my mind), haven't done anything at all interesting, and dragged from them the kind of performances that ache with sincerity and depth of emotion, sometimes flirting near to melodrama, but always perfectly attuned to the place in the film's emotional arc that Campion requires.

And of course, it's handsomely mounted. With production and costume design by Campion's regular collaborator Janet Patterson, the movie is full of exquisite details,, rich with information but never fussy (the use of color in the movie, particularly in regards to Fanny's self-designed dresses, would deserve a multi-thousand-word exploration all on its own), and lived-in to a degree that these Oscarbaity costume dramas virtually never are. The world of Bright Star is living and breathing, not the home of Regency caricatures but of actual people with actual emotions, even if the details of their lives are alien to modern eyes. And like all of Campion's films, it is a triumph of cinematography; here she works with Greig Fraser, after making two short films together, and the argument she makes for his merits is almost as compelling as her rehabilitation of Cornish and Whishaw. Bright Star is a lovely movie, and beyond that, it is a movie of the most careful compositions and focus (Campion's films always have the most evocative focal planes; nothing has topped Sweetie in my mind, but it's uncommon and terribly exciting for an auteur to be noted for her experiments in focal depth and lenses). One of the best-shot films of the year by far, and one of the prettiest, and it's rather special for those two things to overlap.

The film has enough flaws that you cannot ignore them, though I think they are not at all serious. Keats's best friend, Charles Armitage Brown, is used in a very functional way that diminishes him as a character, though Paul Schneider (a great, criminally under-used actor, who you might recognise from All the Real Girls, and if you do not, then for fuck's sake, go watch All the Real Girls) makes a Herculean effort to give the character more depth than "angry Scot with a homosocial crush on John Keats". Far too much of the narrative weight is borne by Fanny's two young siblings, Samuel (Thomas Sangster) and Toots (Edie Martin), particularly in the center of the film where every scene starts to feel like every other scene a little bit. The film lacks exploding robots.

These are small issues, though, in light of what makes the film so damn good: it is the richest depiction of love that I've seen in ages, and what it lacks in straight-up honest, it makes up for in truth. Bright Star is an unbearably beautiful movie, far more emotionally resonant than a prestige picture at the dawn of awards season has any right to be.

Bright Star is a truncated version of the real-life story of English Romantic poet John Keats (Ben Whishaw), and Fanny Brawne (Abbie Cornish), the young woman that he met in the last years of his life, and with whom he shared a passionate love affair that was cut short by Keats's death in 1821 of tuberculosis, at the slight age of 25. It is not to be understood that it is therefore a biopic. For most filmmakers, this would be a story about Keats the great poet, reaching his greatest heights of inspiration from the overwhelming power of love (including the composition of a famous sonnet that gives the film its title in the opening line, "Bright star! would I were steadfast as thou art"). In Campion's hands, though, Keats not only fails to be the protagonist (though he certainly counts as a co-lead, the films is clearly "about" Fanny), nothing within the movie requires that we the audience know him to be a great man of British literature; indeed, it could function just as well if Keats had been lost to history, or if he was an invented figure altogether. Insofar as the poet's later fame informs Bright Star whatsoever, it's only in that the story of the two lovers only came to prominence because Keats later became famous, and thus Campion was able to use their real-life relationship as the springboard for her movie.

And what a movie! It's a love story like they don't make any more, except I'm not certain that they ever really did. That is the whole entire theme of this film: only Brokeback Mountain in recent English-language cinema has been so completely and solely about the act of romance. But even that film - which I adore - is fairly simple in its approach to the classical love story model (make one of the men a woman, and it becomes a very well-mounted but totally straightforward drama). For Campion, a great experimental filmmaker whose experiments have yet to be fully appreciated by a critical establishment that is largely content to ignore everything she made before and after The Piano, the reason to tell a love story involving a poet is so you can make a cinematic poem; and Bright Star indeed fails to do any of the things we might expect of a costume drama romance, in favor of creating a mood that is love, rendered in a manner more poetical than narrative.

Campion has Keats himself provide the key to the movie, in a lesson on poetics to Fanny that I would love to have memorised: the thrust is that when you are in a lake, the purpose is not to analyse what about it is "lakey", but to feel and experience and understand the sensation of being in a lake; that is poetry. You do not break a poem down into its constituent atoms and hold it under a microscope, but you let the poem surround you and fill you with its emotion directly and without mediation. (He perhaps echoes Emily Dickinson's letters: "If I feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that is poetry"). Thus with Bright Star, which very nearly fails to tell a story at all: like most of Campion's films, almost as much effort is put into keeping information from the audience as to providing it. The primary example in the present film comes almost at the moment it starts, when Fanny seems smitten with Keats so instantly that we can't help but wonder why; certainly nothing he's said or done, although to be fair, looking like Ben Whishaw is a fairly compelling reason.

These narrative ellipses (and though I named the one example, the film is dense with them, particularly as regards the passage of time) are unsatisfying in e.g. a biopic, but they are sensible and necessary if the point of the film is simply to present variations over the course of two hours on an emotional state; and that is, without a doubt, the point of Bright Star. It is Jane Campion's poem on being in love, with its ups and downs and exhaustions and exhilarations. And a most beautifully executed poem it is. In Cornish and Whishaw, the director has taken two pretty, vacant young actors who (to my mind), haven't done anything at all interesting, and dragged from them the kind of performances that ache with sincerity and depth of emotion, sometimes flirting near to melodrama, but always perfectly attuned to the place in the film's emotional arc that Campion requires.

And of course, it's handsomely mounted. With production and costume design by Campion's regular collaborator Janet Patterson, the movie is full of exquisite details,, rich with information but never fussy (the use of color in the movie, particularly in regards to Fanny's self-designed dresses, would deserve a multi-thousand-word exploration all on its own), and lived-in to a degree that these Oscarbaity costume dramas virtually never are. The world of Bright Star is living and breathing, not the home of Regency caricatures but of actual people with actual emotions, even if the details of their lives are alien to modern eyes. And like all of Campion's films, it is a triumph of cinematography; here she works with Greig Fraser, after making two short films together, and the argument she makes for his merits is almost as compelling as her rehabilitation of Cornish and Whishaw. Bright Star is a lovely movie, and beyond that, it is a movie of the most careful compositions and focus (Campion's films always have the most evocative focal planes; nothing has topped Sweetie in my mind, but it's uncommon and terribly exciting for an auteur to be noted for her experiments in focal depth and lenses). One of the best-shot films of the year by far, and one of the prettiest, and it's rather special for those two things to overlap.

The film has enough flaws that you cannot ignore them, though I think they are not at all serious. Keats's best friend, Charles Armitage Brown, is used in a very functional way that diminishes him as a character, though Paul Schneider (a great, criminally under-used actor, who you might recognise from All the Real Girls, and if you do not, then for fuck's sake, go watch All the Real Girls) makes a Herculean effort to give the character more depth than "angry Scot with a homosocial crush on John Keats". Far too much of the narrative weight is borne by Fanny's two young siblings, Samuel (Thomas Sangster) and Toots (Edie Martin), particularly in the center of the film where every scene starts to feel like every other scene a little bit. The film lacks exploding robots.

These are small issues, though, in light of what makes the film so damn good: it is the richest depiction of love that I've seen in ages, and what it lacks in straight-up honest, it makes up for in truth. Bright Star is an unbearably beautiful movie, far more emotionally resonant than a prestige picture at the dawn of awards season has any right to be.