Car men

This is a very "based in 2008" review, especially in the opening grafs, but I'm sticking with it. Apologies.

I've wanted to write this for a long time, but there was never a perfect excuse to do it before now.

Clint Eastwood, regarded as something of a master of cinema by many (not all!) traditional media film critics, is generally disdained, even hated, by the great majority of bloggers and other internet-based movie people; this is indeed one of the few issues on which there's a clear distinction between print and internet critics. As a long-time fan of the director - I was on board the "Best Living American Filmmaker" bandwagon before there even was a blogosphere - I've always felt a bit disappointed by that distinction, which I think traces back to the notorious 2004 Oscars, when Eastwood beat the perpetual bridesmaid Martin Scorsese to a Best Director award, having unforgivably done better work directing a superior film. Maybe that's being bigoted against my fellow internet film buffs, who might very well have an actual legitimate reason to dislike the man that isn't based in his admittedly very obvious Oscarbaiting tendencies; at any rate, the Scorsese connection ought to have been wiped clear in 2006, when Marty's tired work on a bland crime drama beat one of Eastwood's best films ever to the top two awards. But I haven't come here to go on and on about how Scorsese needed to retire in 1990, while Clint has spent the last decade making the most interesting films of his career.

I have come here instead to praise Gran Torino, not perhaps the best of Eastwood's recent films, but a fairly perfect example of all the things that make people like me break out phrases like "the best living American filmmaker" when his name comes up. That is, it's the most typical film he's made during his renaissance that started up in 2003, and therefore an ideal place to mount all sorts of overly-enthusiastic arguments about the director's aesthetic.

This isn't something I've ever seen in print before, but I don't imagine that anybody would violently disagree: Eastwood has spent his entire 37-year career as a director emulating Don Siegel, with whom he made five movies between 1968 and 1979, and to whom he co-dedicated his 1992 masterpiece Unforgiven. Siegel, for the uninitiated, was one of a generation of filmmakers during the 1940s, '50s and '60s who made extremely pulpy films with a brutally simple, direct aesthetic, a group of men who essentially and probably unconsciously applied the literary techniques of Ernest Hemingway to cinema. Such directors are all but extinct in the modern world, with Eastwood the single working representative, to the best of my knowledge, of a tradition that has included the likes of Sam Fuller, Nicholas Ray, Anthony Mann and Budd Boetticher.

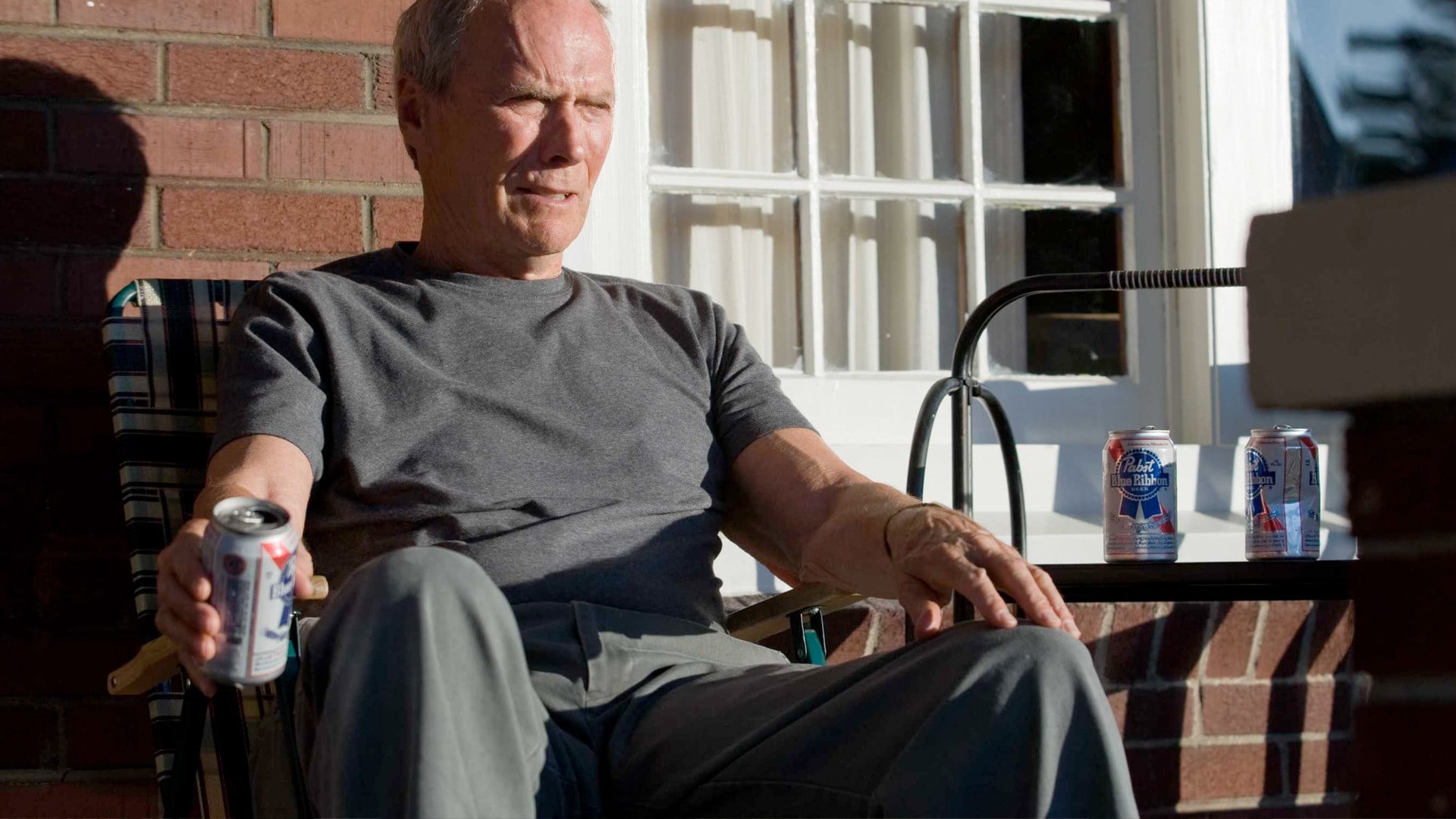

Right from the start, Eastwood subscribed to these men's stripped-down style, though not always with great success - for every early Outlaw Josey Wales there's a Firefox. Like many great pulp directors, Eastwood hasn't always selected or been given the best screenplays, and his ability to overcome a weak script is historically uneven. Still, for those whose formal tastes run towards the lean and masculine, nearly all of his films have had some small compensation, no matter how poor the writing. Of late, Eastwood's aesthetic has reached a harsh perfection: in his pair of neo-noirs Mystic River and Million Dollar Baby (neither of which has been fully appreciated in terms of its position relative to the great 1950s films noirs), and in his nihilistically dispassionate World War II dyad Flags of Our Fathers and Letters of Iwo Jima, he has reached a conservative formalist utopia in which theme, narrative and character are all functions of lighting and camera angle. He hit a snag with Changeling, an over-written, visually stuffy period piece-cum-cop thriller, but in Gran Torino the Clint that I grew up with has come roaring back: he's finally married his newly-perfected skills as a visual storyteller to the kind of stories that he's been part of throughout his career as actor and director - "Dirty" Harry Callahan as a hateful retiree, filtered through Tom Stern's unforgiving, monochromatic camera lens.

Gran Torino is the story of a Korean War vet and retired Detroit autoworker named Walt Kowalski, whom we meet at his wife's funeral. Walt is a dick. There's no other way to put. Sure, Eastwood and screenwriter Nick Schenk disguise that fact a bit by contrasting Walt against his even worse family, and by presenting Walt as a comic figure in the early going (All those silly moments in the trailer, which seemed so serious, but everybody laughed at them? Turns out we were supposed to laugh). But it's not possible to see Walt's casual racism against pretty much every ethnic group that can be found in Detriot, and his delight in making fun of a young priest (Christopher Carley) just because he can get away with it, and assume that we're meant to find him at all respectable. Without getting into the details, Walt is forced into a modern multicultural world that he's not really anxious to face when the Hmong family next door is threatened by a local gang, and without meaning to, the old crank takes the teenaged Thao (Bee Vang) under his wing, with the boy and man bonding over icons of masculine identity, like tools, yardwork, and Walt's pristine 1972 Ford Gran Torino.

The film's programmatic depiction of Walt's transition from xenophobe to grudging member of a changing America is hardly subtle, and at times the film lurches into well-intentioned racism itself, particularly in the form of Thao's sister Sue (Ahney Her) - I've spent a lot of time trying to figure out if Sue's didactic, on-the-nose dialogue is the result of poor acting, poor writing, or very canny acting and writing meant to suggest that the young woman is pretending to have a better grasp of her adopted language than is the case; but the fact that I can question this at all doesn't augur in the film's favor. Yet I simply can't get myself very worked up over the gaping flaws in the screenplay, simply because in every other way, Gran Torino feels like a proud throwback to the pulp message pictures of the 1950s; and none of those films were particularly subtle or sensitive. Honestly, Gran Torino feels like Eastwood's most Sam Fuller-y film ever, chiefly in its fetishistic treatment of the Korean War and its ethnographic obsession with an obscure ethnic group. Sure, it's watered-down Fuller, but that's a lot better than no Fuller at all, which is what we get in essentially every other movie that exists these days.

Besides, Eastwood has the directorial chops to justify the comparison, almost. Gran Torino isn't the formal masterpiece that Million Dollar Baby was, but it's impeccably shot and except for a handful of shots that clearly go on for a few frames too long, every single cut seems to serve a purpose. There's an urgency born from necessity when a film is produced quickly: without time to waste on set, every shot has to mean something, else it doesn't justify the set-up time. This is the secret behind some of Fuller's best work of the 1950s, and the fact that Gran Torino had the fastest turnaround time of any Eastwood film this decade shows: it's incredibly lean, the first of the director's films under two hours since 2002's Blood Work.

Before I say goodbye to the film, I would be a fool to ignore the elephant in the room: Eastwood himself plays Walt, and he claims that with this film, he retires from acting. It's not hard to believe him: the film is plainly a goodbye to the Dirty Harry persona that, along with the Man With No Name (who was disposed of in Unforgiven), underlies every other Eastwood character. The performance itself doesn't necessarily rate among the actor's best: Million Dollar Baby had a much better portrait of the artist as an old man, and several of his '90s films showcased a more interesting idea of a man tormented by the violence he has done and must continue to do. But it's a fine farewell, much better than e.g. Woody Allen in Scoop. That Eastwood is a great performer I'm taking as written; of course, like his fellow Western icon John Wayne, there continue to be an (ever-dwindling) number of people who mistake his limited range for a lack of talent, but I'll just let those people find enlightenment themselves.

Look, not everyone is going to like Gran Torino. It's undeniably hokey. But all pulp fiction is ultimately a little hokey, and that's usually why the makers of such movies compensate by bringing their A-game behind the camera. I can't make anybody love Eastwood's aesthetic, but for those who do, this is a giant step up from Changeling, and different enough from his great films in the middle of the decade to demonstrate conclusively that old age hasn't led the director into a comfort zone: he continues to find new and sometimes weird ways to challenge himself creatively. Gran Torino may be lopsided, hammy and overdetermined, but those are exactly the reasons I'm compelled to call it a great movie.

I've wanted to write this for a long time, but there was never a perfect excuse to do it before now.

Clint Eastwood, regarded as something of a master of cinema by many (not all!) traditional media film critics, is generally disdained, even hated, by the great majority of bloggers and other internet-based movie people; this is indeed one of the few issues on which there's a clear distinction between print and internet critics. As a long-time fan of the director - I was on board the "Best Living American Filmmaker" bandwagon before there even was a blogosphere - I've always felt a bit disappointed by that distinction, which I think traces back to the notorious 2004 Oscars, when Eastwood beat the perpetual bridesmaid Martin Scorsese to a Best Director award, having unforgivably done better work directing a superior film. Maybe that's being bigoted against my fellow internet film buffs, who might very well have an actual legitimate reason to dislike the man that isn't based in his admittedly very obvious Oscarbaiting tendencies; at any rate, the Scorsese connection ought to have been wiped clear in 2006, when Marty's tired work on a bland crime drama beat one of Eastwood's best films ever to the top two awards. But I haven't come here to go on and on about how Scorsese needed to retire in 1990, while Clint has spent the last decade making the most interesting films of his career.

I have come here instead to praise Gran Torino, not perhaps the best of Eastwood's recent films, but a fairly perfect example of all the things that make people like me break out phrases like "the best living American filmmaker" when his name comes up. That is, it's the most typical film he's made during his renaissance that started up in 2003, and therefore an ideal place to mount all sorts of overly-enthusiastic arguments about the director's aesthetic.

This isn't something I've ever seen in print before, but I don't imagine that anybody would violently disagree: Eastwood has spent his entire 37-year career as a director emulating Don Siegel, with whom he made five movies between 1968 and 1979, and to whom he co-dedicated his 1992 masterpiece Unforgiven. Siegel, for the uninitiated, was one of a generation of filmmakers during the 1940s, '50s and '60s who made extremely pulpy films with a brutally simple, direct aesthetic, a group of men who essentially and probably unconsciously applied the literary techniques of Ernest Hemingway to cinema. Such directors are all but extinct in the modern world, with Eastwood the single working representative, to the best of my knowledge, of a tradition that has included the likes of Sam Fuller, Nicholas Ray, Anthony Mann and Budd Boetticher.

Right from the start, Eastwood subscribed to these men's stripped-down style, though not always with great success - for every early Outlaw Josey Wales there's a Firefox. Like many great pulp directors, Eastwood hasn't always selected or been given the best screenplays, and his ability to overcome a weak script is historically uneven. Still, for those whose formal tastes run towards the lean and masculine, nearly all of his films have had some small compensation, no matter how poor the writing. Of late, Eastwood's aesthetic has reached a harsh perfection: in his pair of neo-noirs Mystic River and Million Dollar Baby (neither of which has been fully appreciated in terms of its position relative to the great 1950s films noirs), and in his nihilistically dispassionate World War II dyad Flags of Our Fathers and Letters of Iwo Jima, he has reached a conservative formalist utopia in which theme, narrative and character are all functions of lighting and camera angle. He hit a snag with Changeling, an over-written, visually stuffy period piece-cum-cop thriller, but in Gran Torino the Clint that I grew up with has come roaring back: he's finally married his newly-perfected skills as a visual storyteller to the kind of stories that he's been part of throughout his career as actor and director - "Dirty" Harry Callahan as a hateful retiree, filtered through Tom Stern's unforgiving, monochromatic camera lens.

Gran Torino is the story of a Korean War vet and retired Detroit autoworker named Walt Kowalski, whom we meet at his wife's funeral. Walt is a dick. There's no other way to put. Sure, Eastwood and screenwriter Nick Schenk disguise that fact a bit by contrasting Walt against his even worse family, and by presenting Walt as a comic figure in the early going (All those silly moments in the trailer, which seemed so serious, but everybody laughed at them? Turns out we were supposed to laugh). But it's not possible to see Walt's casual racism against pretty much every ethnic group that can be found in Detriot, and his delight in making fun of a young priest (Christopher Carley) just because he can get away with it, and assume that we're meant to find him at all respectable. Without getting into the details, Walt is forced into a modern multicultural world that he's not really anxious to face when the Hmong family next door is threatened by a local gang, and without meaning to, the old crank takes the teenaged Thao (Bee Vang) under his wing, with the boy and man bonding over icons of masculine identity, like tools, yardwork, and Walt's pristine 1972 Ford Gran Torino.

The film's programmatic depiction of Walt's transition from xenophobe to grudging member of a changing America is hardly subtle, and at times the film lurches into well-intentioned racism itself, particularly in the form of Thao's sister Sue (Ahney Her) - I've spent a lot of time trying to figure out if Sue's didactic, on-the-nose dialogue is the result of poor acting, poor writing, or very canny acting and writing meant to suggest that the young woman is pretending to have a better grasp of her adopted language than is the case; but the fact that I can question this at all doesn't augur in the film's favor. Yet I simply can't get myself very worked up over the gaping flaws in the screenplay, simply because in every other way, Gran Torino feels like a proud throwback to the pulp message pictures of the 1950s; and none of those films were particularly subtle or sensitive. Honestly, Gran Torino feels like Eastwood's most Sam Fuller-y film ever, chiefly in its fetishistic treatment of the Korean War and its ethnographic obsession with an obscure ethnic group. Sure, it's watered-down Fuller, but that's a lot better than no Fuller at all, which is what we get in essentially every other movie that exists these days.

Besides, Eastwood has the directorial chops to justify the comparison, almost. Gran Torino isn't the formal masterpiece that Million Dollar Baby was, but it's impeccably shot and except for a handful of shots that clearly go on for a few frames too long, every single cut seems to serve a purpose. There's an urgency born from necessity when a film is produced quickly: without time to waste on set, every shot has to mean something, else it doesn't justify the set-up time. This is the secret behind some of Fuller's best work of the 1950s, and the fact that Gran Torino had the fastest turnaround time of any Eastwood film this decade shows: it's incredibly lean, the first of the director's films under two hours since 2002's Blood Work.

Before I say goodbye to the film, I would be a fool to ignore the elephant in the room: Eastwood himself plays Walt, and he claims that with this film, he retires from acting. It's not hard to believe him: the film is plainly a goodbye to the Dirty Harry persona that, along with the Man With No Name (who was disposed of in Unforgiven), underlies every other Eastwood character. The performance itself doesn't necessarily rate among the actor's best: Million Dollar Baby had a much better portrait of the artist as an old man, and several of his '90s films showcased a more interesting idea of a man tormented by the violence he has done and must continue to do. But it's a fine farewell, much better than e.g. Woody Allen in Scoop. That Eastwood is a great performer I'm taking as written; of course, like his fellow Western icon John Wayne, there continue to be an (ever-dwindling) number of people who mistake his limited range for a lack of talent, but I'll just let those people find enlightenment themselves.

Look, not everyone is going to like Gran Torino. It's undeniably hokey. But all pulp fiction is ultimately a little hokey, and that's usually why the makers of such movies compensate by bringing their A-game behind the camera. I can't make anybody love Eastwood's aesthetic, but for those who do, this is a giant step up from Changeling, and different enough from his great films in the middle of the decade to demonstrate conclusively that old age hasn't led the director into a comfort zone: he continues to find new and sometimes weird ways to challenge himself creatively. Gran Torino may be lopsided, hammy and overdetermined, but those are exactly the reasons I'm compelled to call it a great movie.