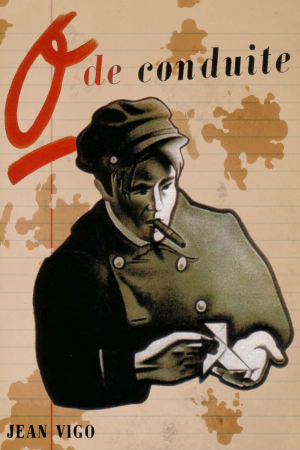

They Shoot Pictures, Don't They? 2008 Edition - #263

Complaining "this film suffers from too much ambition" isn't something you get to do very often, but it's still a fairly easy and facile criticism. But occasionally, it just fits perfectly, and if ever I've seen a film that seems, objectively, to be the poster child for movies that are being pressed to do too many things with too few resources, it would undoubtedly be Zero for Conduct, the third of the too-short-lived director Jean Vigo's four films, and arguably his first feature - the argument being over the question of whether any movie that runs for just 41 minutes counts as a feature (the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences says "yes", and who am I to argue with that august body?).

I must confess myself stumped. I have no idea why the film is so amazingly short, and I haven't been able to find anything on the internet to explain it in anything more than a vague guess - this on the medium that permits me to find a dozen sites of women with golf balls stuffed into their rectums in less than five seconds. Sometimes I do wonder about this whole "Western Culture" thing. Anyway, it doesn't really matter: whatever the reason for Zero for Conduct to end up at 41 minutes, that is all the longer that it is, and that is the movie that we must grapple with. Those 41 minutes are all pretty great, but they're also overwhelming: Vigo clearly had a good 80 or 90 minutes worth of movie that he had to fit into half the running time, and the result is one of the densest, highest-potency narrative films of all time.

The sketchy, sometimes confusing and borderline Surrealist narrative concerns a crummy little boarding school in France, where the principal (Delphin) is an egomaniacal midget with a giant beard, the chemistry teacher has an unacceptably keen admiration for the young male form, and the menu of every meal, day in and out, is a plate of wet beans. Should the boys dare to speak loudly against the totalitarian regime in charge of their daily lives, they're slapped with the dreaded mark of "zero for conduct", meaning detention on the weekend and if it were possible, even worse treatment. The only halfway decent teacher, one Huguet (Jean Dasté), is powerless to stop any of these outrages, and is generally viewed as a bit of a clown by both faculty and student body. Not that the kids are angels: the first time we see our young heroes, Caussat (Louis Lefebvre) and Bruel (Coco Golstein), they're on a train back from holidays being general hellions and sneaking cigars. So it's not surprising when these "young devils" (according to the film's French subtitle) plan a revolution, although that revolution will prove to be much more charming and much less violent than in the film's crypto-remake from 1968, if....

Still, it was enough for the French government to panic a little at the film's allegorical attack on The Way Things Are, and Zero for Conduct was consigned to a 12-year ban, yet another of the seemingly infinite satires of the bourgeoisie given such treatment. Nowadays, that treatment seems more than a little quaint (much like the savage reception accorded the delightful and achingly beautiful The Rules of the Game, six years later), largely because of the outsized influence this poetic little 41 minute snip of a film has had on subsequent film history (among others, François Truffaut lifted shots intact for his The 400 Blows), rendering its then-shocking treatment of rebellious little kids into appealing cliché, and all but guaranteeing that a modern viewer is going to be taken by its marvelous visual poetry than by its outdated revolutionary content. But let us not be too hasty to forget the historical context of Zero for Conduct, a deeply personal work for the director, who as an orphaned child spend his formative years in places much like the one depicted onscreen. Perhaps we are not moved by the same things a radical Frenchman would have seen in a clandestine screening in 1933, but those things are nonetheless part of the film's rich history.

But yeah, how about that visual poetry? With the director's first two films, both of them short documentaries, generally forgotten even by scholars, Jean Vigo's entire reputation rests on this featurette and the following year's L'Atalante, barely released before his unacceptably premature death at 29. Quite the heady reputation it is, too, considering how little we have to base it on; yet Zero for Conduct and L'Atalante are both among the finest early sound films in existence. Zero for Conduct enjoys neither the relative fame or reputation of its successor, and I'm not inclined to argue that it shouldn't be the case: L'Atalante is tremendously brilliant in almost every regard, while the shorter film feels more like the basis for a flat-out masterpiece than a masterpiece in itself. I'd compare the two films to Orson Welles's first features: Citizen Kane is better known and admittedly better than The Magnificent Ambersons, but only because the latter film is clearly chopped apart and corrupted; frame-for-frame, though, Ambersons is quite possibly the superior work. Similarly, Zero for Conduct might better L'Atalante if only it were a bit less rushed, a bit clearer in its plot, and had a bit more money been thrown at the production (among other signs of cheapness, the sound is tinny even by 1933 French standards).

Yet what we have of Zero for Conduct is nothing shy of amazing, doubly so when we recall that Vigo had never directed a fictional narrative before. This man was, simply out, a natural born filmmaker, and if this is what he was capable of the first time at bat, it's hard not to be angry that he lived for such a short moment in time. The imagery in this film, shot (like all of Vigo's films) by Boris Kaufman, younger brother of the revolutionary Soviet filmmaker Dziga Vertov (born Denis Kaufman), is poetically beautiful and timeless, infinitely copied but never improved upon. The slow-motion pillow fight that the boys stage as a practice run for the next day's sabotage of an important alumni event turns into a ballet of drifting feathers and bodies in motion; the frequent use of unexpected camera angles - such as canted-angle, bird's-eye perspectives of the schoolyard - give the school the menacing air of a magically realist fairy tale; and then there's the frequent, playful tricks that Vigo has up his sleeve, from a scornful drawing of Huguet's clowning that turns into an animated cartoon (shades of the Fleischers, for this viewer), to the portrait over a fireplace that's actually a mirror, mimicking the position of the angry little man standing underneath, to the cardboard cut-outs that stand in for the directors of the school in what might have been a cost-cutting measure, but certainly stands as the film's most wicked bit of satire.

In short, it is a marvelous film, and if it's not quite up to L'Atalante, I can't imagine that anyone would regard it as a failure for that reason - most films are not as visually marvelous as L'Atalante. Only its desire to cram the whole of childhood into such a slight framework, with the arbitrary narrative confusion that follows, really stands out as a flaw. Both for its influence and its own inherent quality, Zero for Conduct truly is one of the key films of the early sound era.

I must confess myself stumped. I have no idea why the film is so amazingly short, and I haven't been able to find anything on the internet to explain it in anything more than a vague guess - this on the medium that permits me to find a dozen sites of women with golf balls stuffed into their rectums in less than five seconds. Sometimes I do wonder about this whole "Western Culture" thing. Anyway, it doesn't really matter: whatever the reason for Zero for Conduct to end up at 41 minutes, that is all the longer that it is, and that is the movie that we must grapple with. Those 41 minutes are all pretty great, but they're also overwhelming: Vigo clearly had a good 80 or 90 minutes worth of movie that he had to fit into half the running time, and the result is one of the densest, highest-potency narrative films of all time.

The sketchy, sometimes confusing and borderline Surrealist narrative concerns a crummy little boarding school in France, where the principal (Delphin) is an egomaniacal midget with a giant beard, the chemistry teacher has an unacceptably keen admiration for the young male form, and the menu of every meal, day in and out, is a plate of wet beans. Should the boys dare to speak loudly against the totalitarian regime in charge of their daily lives, they're slapped with the dreaded mark of "zero for conduct", meaning detention on the weekend and if it were possible, even worse treatment. The only halfway decent teacher, one Huguet (Jean Dasté), is powerless to stop any of these outrages, and is generally viewed as a bit of a clown by both faculty and student body. Not that the kids are angels: the first time we see our young heroes, Caussat (Louis Lefebvre) and Bruel (Coco Golstein), they're on a train back from holidays being general hellions and sneaking cigars. So it's not surprising when these "young devils" (according to the film's French subtitle) plan a revolution, although that revolution will prove to be much more charming and much less violent than in the film's crypto-remake from 1968, if....

Still, it was enough for the French government to panic a little at the film's allegorical attack on The Way Things Are, and Zero for Conduct was consigned to a 12-year ban, yet another of the seemingly infinite satires of the bourgeoisie given such treatment. Nowadays, that treatment seems more than a little quaint (much like the savage reception accorded the delightful and achingly beautiful The Rules of the Game, six years later), largely because of the outsized influence this poetic little 41 minute snip of a film has had on subsequent film history (among others, François Truffaut lifted shots intact for his The 400 Blows), rendering its then-shocking treatment of rebellious little kids into appealing cliché, and all but guaranteeing that a modern viewer is going to be taken by its marvelous visual poetry than by its outdated revolutionary content. But let us not be too hasty to forget the historical context of Zero for Conduct, a deeply personal work for the director, who as an orphaned child spend his formative years in places much like the one depicted onscreen. Perhaps we are not moved by the same things a radical Frenchman would have seen in a clandestine screening in 1933, but those things are nonetheless part of the film's rich history.

But yeah, how about that visual poetry? With the director's first two films, both of them short documentaries, generally forgotten even by scholars, Jean Vigo's entire reputation rests on this featurette and the following year's L'Atalante, barely released before his unacceptably premature death at 29. Quite the heady reputation it is, too, considering how little we have to base it on; yet Zero for Conduct and L'Atalante are both among the finest early sound films in existence. Zero for Conduct enjoys neither the relative fame or reputation of its successor, and I'm not inclined to argue that it shouldn't be the case: L'Atalante is tremendously brilliant in almost every regard, while the shorter film feels more like the basis for a flat-out masterpiece than a masterpiece in itself. I'd compare the two films to Orson Welles's first features: Citizen Kane is better known and admittedly better than The Magnificent Ambersons, but only because the latter film is clearly chopped apart and corrupted; frame-for-frame, though, Ambersons is quite possibly the superior work. Similarly, Zero for Conduct might better L'Atalante if only it were a bit less rushed, a bit clearer in its plot, and had a bit more money been thrown at the production (among other signs of cheapness, the sound is tinny even by 1933 French standards).

Yet what we have of Zero for Conduct is nothing shy of amazing, doubly so when we recall that Vigo had never directed a fictional narrative before. This man was, simply out, a natural born filmmaker, and if this is what he was capable of the first time at bat, it's hard not to be angry that he lived for such a short moment in time. The imagery in this film, shot (like all of Vigo's films) by Boris Kaufman, younger brother of the revolutionary Soviet filmmaker Dziga Vertov (born Denis Kaufman), is poetically beautiful and timeless, infinitely copied but never improved upon. The slow-motion pillow fight that the boys stage as a practice run for the next day's sabotage of an important alumni event turns into a ballet of drifting feathers and bodies in motion; the frequent use of unexpected camera angles - such as canted-angle, bird's-eye perspectives of the schoolyard - give the school the menacing air of a magically realist fairy tale; and then there's the frequent, playful tricks that Vigo has up his sleeve, from a scornful drawing of Huguet's clowning that turns into an animated cartoon (shades of the Fleischers, for this viewer), to the portrait over a fireplace that's actually a mirror, mimicking the position of the angry little man standing underneath, to the cardboard cut-outs that stand in for the directors of the school in what might have been a cost-cutting measure, but certainly stands as the film's most wicked bit of satire.

In short, it is a marvelous film, and if it's not quite up to L'Atalante, I can't imagine that anyone would regard it as a failure for that reason - most films are not as visually marvelous as L'Atalante. Only its desire to cram the whole of childhood into such a slight framework, with the arbitrary narrative confusion that follows, really stands out as a flaw. Both for its influence and its own inherent quality, Zero for Conduct truly is one of the key films of the early sound era.