Under the Tuscan sun

Every new Spike Lee joint brings with it the question, was this directed by the good Spike Lee or the bad Spike Lee? And while Miracle at St. Anna was fairly clearly directed by the bad Spike Lee, it's the best bad film he's ever directed. Is that circular enough? Anyway, I know you've probably heard this before, but Lee is the kind of filmmaker whose personality is vibrant enough that he's incapable of making a movie so absolutely terrible that it isn't at least very interesting - even She Hate Me and Girl 6 aren't complete wastes of celluloid. It's a cliché to say that about this director, but only because it's so very, very true.

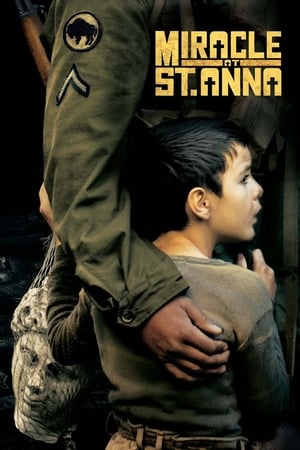

So, Miracle at St. Anna: a film where you could probably recap the plot, but only at the expense of a great many words. The shortest version is that it's a story about four African-American soldiers in Italy in 1944, and what they found there. My guess, based in no small part on the embarrassing (to both parties) tiff that Lee had with Clint Eastwood a little while back, is that he was first drawn to the project on the appeal of making a film that would celebrate the black experience of World War II, a conflict that has cinematically been given a very white treatment in films like Saving Private Ryan and Eastwood's Flags of Our Fathers, to say nothing of the older school of Hollywood war pictures, back when racism wasn't even hidden. That Lee's film, adapted by James McBride from his own novel, should fancy itself a deliberate corrective to the received cinematic tradition is quite obvious from the first scene, set in 1983, as an aged black man named Hector Negron (Laz Alonso) watches the 1962 John Wayne vehicle The Longest Day in his lonely apartment, and murmurs, "We fought for the country, too". You don't get much more forthright about your goals than that.

Then, and here's the perplexing thing, the film starts chasing rabbits every which way and a very sizable chunk of the whole ends up having not a damn thing to do with the black soldier in WWII at all. The main thrust of the plot follows four young African-Americans from George Company of the Buffalo Soldiers: Corporal Negron, Sergeant Aubrey Stamps (Derek Luke), Sergeant Bishop Cummings (Michael Ealy), and Private Sam Train (Omar Benson Miller), as they accidentally slip through German lines in the mountains of Tuscany, finding a lost boy (Matteo Sciabordi), and hiding out in a nameless village, home to a dead-ender Fascist sympathiser (Omero Antonutti), his lovely English-speaking daughter Renata (Valentina Cervi), and Peppi Grotta (Pierfrancesco Favino), a Partisan leader so successful in his tactics that the Nazis have levied a sizable price on his head, though they know only his pseudonym, "The Butterfly". All this is meant to answer a mystery posed in the film's framework narrative: why did Hector, an elderly postal employee, shoot a man in cold blood who happened to walk into his post office, and how was the murder connected to the extraordinarily valuable statue head that the police found buried in a closet in Hector's apartment?

Let's see... we've got "film about the African-American view of the war", we've got "film about how the battle between Fascists and Partisans tore apart the communal fabric in Italy", and we've got "mystery about what happened back in the war, and how it still reverberates today". That enough for you? No? Then add a recurring motif of religious mysticism and the miraculous ways that God works in times of battle, plenty of sequences that step out from the main plot and explore the institutionalised racism of the American military and the American South in the 1940s, and a handful of scenes that take place amongst the Nazis, just, well, just because. Frankly, this is what we love about Spike Lee: when he lands on an idea that interests him, he'll find a way to work it into his movie, and that's why Miracle at St. Anna ends up with a 160 minute running time despite an A-plot which requires, at best, two-thirds of that length. It leaves the film a messy patchwork of ideas spinning off every which way, and increasingly absurd mysteries and coincidences that get piled one on top of the other, but which all end up tied together tightly, though not very neatly.

The final product isn't a patch on Eastwood's Flags or Letters from Iwo Jima, which makes the feud that much more disingenuous. But again, failing to be good doesn't mean that it's not interesting, and it's one of the most curious elements of Miracle at St. Anna that of the bits and pieces that are the most extraneous are generally the best parts, taken individually. I expect that these are the parts which interested Lee the most; there's a sharp divide between the places where he fully unfurls his estimable talents as a filmmaker, and those where he mostly just sets up the camera and has the actors walk in front of it, and for the most part the mechanical plot-advancing parts of the movies are the ones that have been indifferently tossed-off. But the random add-ins, now those have a lot of love in them. Case in point: early on, as George and Fox company are trying to cross a heavily guarded river, the Nazis wheel up a truck broadcasting the morale-depleting words of Axis Sally (Alexandra Maria Lara). The American soldiers wade across, trying not to let her obvious lies about Hitler's love of the negro and uncomfortable truths about the contempt in which most white Americans held their compatriots discomfit them; the Nazis bitch and moan about how the loud broadcast makes it impossible for them to think. Occasionally, Lee cuts to shots of Sally in her opulent Third Reich broadcast booth, draped in red velvet and swastikas, as she coos into the mike. This goes on for what feels like five minutes at least, and makes no point that couldn't have been made in a tenth of the time, but Lee is obviously fascinated by the whole set-up, and pulls out any number of tricks with cross-cutting and camera movement. The result is one of the film's most exhilarating scenes, even though it doesn't ultimately mean a damn thing.

Again, these are the flourishes that give the film wings. When Lee actually gets down to business, Miracle at St. Anna crashes into a dreary slog, not just because the filmmaker's fleet touch has been replaced by mirthless lecturing, but because the film's attempt to right the historical record on race just doesn't work. All that really happens is that the traditional white stereotypes of war pictures are replaced with black stereotypes, particularly in the figures of Bishop and Train, the latter of whom shucks and jives with abandon and says things like "Ooh Lawdy!" and "Sweet Jeezus!" It's unpleasant to see racial stereotypes in movies; it's depressing when those stereotypes are perpetrated by minority filmmakers; but when those stereotypes come in movies that minority filmmakers promoted by loudly complaining about the racism in war movies, it's mostly just dumbfounding.

Aside from that, there are just the normal little quibbles: with the story circling 'round the drain for so long, it's hard to keep your attention focused, and the framework mystery is an absolute narrative shambles, almost as bad as the film-wrecking opening and closing scenes in Saving Private Ryan (as an added bonus, the framework enables a clutch of ridiculously distracting cameos from John Leguizamo, John Turturro and Joseph Gordon-Levitt). It's not altogether new for Lee's impulses as a stylist and provocateur to overwhelm his abilities as a storyteller, though after the fleet thriller Inside Man and the tremendous, impassioned documentary When the Levees Broke, one could have maybe hoped that he'd worked some of that out of his system. Whatever. A Spike Lee joint is still a Spike Lee joint, and if nothing else, that means you're not going to walk out bored.

So, Miracle at St. Anna: a film where you could probably recap the plot, but only at the expense of a great many words. The shortest version is that it's a story about four African-American soldiers in Italy in 1944, and what they found there. My guess, based in no small part on the embarrassing (to both parties) tiff that Lee had with Clint Eastwood a little while back, is that he was first drawn to the project on the appeal of making a film that would celebrate the black experience of World War II, a conflict that has cinematically been given a very white treatment in films like Saving Private Ryan and Eastwood's Flags of Our Fathers, to say nothing of the older school of Hollywood war pictures, back when racism wasn't even hidden. That Lee's film, adapted by James McBride from his own novel, should fancy itself a deliberate corrective to the received cinematic tradition is quite obvious from the first scene, set in 1983, as an aged black man named Hector Negron (Laz Alonso) watches the 1962 John Wayne vehicle The Longest Day in his lonely apartment, and murmurs, "We fought for the country, too". You don't get much more forthright about your goals than that.

Then, and here's the perplexing thing, the film starts chasing rabbits every which way and a very sizable chunk of the whole ends up having not a damn thing to do with the black soldier in WWII at all. The main thrust of the plot follows four young African-Americans from George Company of the Buffalo Soldiers: Corporal Negron, Sergeant Aubrey Stamps (Derek Luke), Sergeant Bishop Cummings (Michael Ealy), and Private Sam Train (Omar Benson Miller), as they accidentally slip through German lines in the mountains of Tuscany, finding a lost boy (Matteo Sciabordi), and hiding out in a nameless village, home to a dead-ender Fascist sympathiser (Omero Antonutti), his lovely English-speaking daughter Renata (Valentina Cervi), and Peppi Grotta (Pierfrancesco Favino), a Partisan leader so successful in his tactics that the Nazis have levied a sizable price on his head, though they know only his pseudonym, "The Butterfly". All this is meant to answer a mystery posed in the film's framework narrative: why did Hector, an elderly postal employee, shoot a man in cold blood who happened to walk into his post office, and how was the murder connected to the extraordinarily valuable statue head that the police found buried in a closet in Hector's apartment?

Let's see... we've got "film about the African-American view of the war", we've got "film about how the battle between Fascists and Partisans tore apart the communal fabric in Italy", and we've got "mystery about what happened back in the war, and how it still reverberates today". That enough for you? No? Then add a recurring motif of religious mysticism and the miraculous ways that God works in times of battle, plenty of sequences that step out from the main plot and explore the institutionalised racism of the American military and the American South in the 1940s, and a handful of scenes that take place amongst the Nazis, just, well, just because. Frankly, this is what we love about Spike Lee: when he lands on an idea that interests him, he'll find a way to work it into his movie, and that's why Miracle at St. Anna ends up with a 160 minute running time despite an A-plot which requires, at best, two-thirds of that length. It leaves the film a messy patchwork of ideas spinning off every which way, and increasingly absurd mysteries and coincidences that get piled one on top of the other, but which all end up tied together tightly, though not very neatly.

The final product isn't a patch on Eastwood's Flags or Letters from Iwo Jima, which makes the feud that much more disingenuous. But again, failing to be good doesn't mean that it's not interesting, and it's one of the most curious elements of Miracle at St. Anna that of the bits and pieces that are the most extraneous are generally the best parts, taken individually. I expect that these are the parts which interested Lee the most; there's a sharp divide between the places where he fully unfurls his estimable talents as a filmmaker, and those where he mostly just sets up the camera and has the actors walk in front of it, and for the most part the mechanical plot-advancing parts of the movies are the ones that have been indifferently tossed-off. But the random add-ins, now those have a lot of love in them. Case in point: early on, as George and Fox company are trying to cross a heavily guarded river, the Nazis wheel up a truck broadcasting the morale-depleting words of Axis Sally (Alexandra Maria Lara). The American soldiers wade across, trying not to let her obvious lies about Hitler's love of the negro and uncomfortable truths about the contempt in which most white Americans held their compatriots discomfit them; the Nazis bitch and moan about how the loud broadcast makes it impossible for them to think. Occasionally, Lee cuts to shots of Sally in her opulent Third Reich broadcast booth, draped in red velvet and swastikas, as she coos into the mike. This goes on for what feels like five minutes at least, and makes no point that couldn't have been made in a tenth of the time, but Lee is obviously fascinated by the whole set-up, and pulls out any number of tricks with cross-cutting and camera movement. The result is one of the film's most exhilarating scenes, even though it doesn't ultimately mean a damn thing.

Again, these are the flourishes that give the film wings. When Lee actually gets down to business, Miracle at St. Anna crashes into a dreary slog, not just because the filmmaker's fleet touch has been replaced by mirthless lecturing, but because the film's attempt to right the historical record on race just doesn't work. All that really happens is that the traditional white stereotypes of war pictures are replaced with black stereotypes, particularly in the figures of Bishop and Train, the latter of whom shucks and jives with abandon and says things like "Ooh Lawdy!" and "Sweet Jeezus!" It's unpleasant to see racial stereotypes in movies; it's depressing when those stereotypes are perpetrated by minority filmmakers; but when those stereotypes come in movies that minority filmmakers promoted by loudly complaining about the racism in war movies, it's mostly just dumbfounding.

Aside from that, there are just the normal little quibbles: with the story circling 'round the drain for so long, it's hard to keep your attention focused, and the framework mystery is an absolute narrative shambles, almost as bad as the film-wrecking opening and closing scenes in Saving Private Ryan (as an added bonus, the framework enables a clutch of ridiculously distracting cameos from John Leguizamo, John Turturro and Joseph Gordon-Levitt). It's not altogether new for Lee's impulses as a stylist and provocateur to overwhelm his abilities as a storyteller, though after the fleet thriller Inside Man and the tremendous, impassioned documentary When the Levees Broke, one could have maybe hoped that he'd worked some of that out of his system. Whatever. A Spike Lee joint is still a Spike Lee joint, and if nothing else, that means you're not going to walk out bored.

Categories: movies about wwii, oscarbait, spike lee, war pictures