The dark prince returns

The 1960s saw Hammer Film Productions at the height of its popularity and, arguably, its creativity. Which perhaps goes to explain the strange six-year gap in the flagship Frankenstein and Dracula franchises, as the studio's filmmakers saw fit to explore other avenues in the horror genre, as well as occasional forays into things like pirate movies and literary adventure stories. But whatever the cause, a cash cow is still a cash cow, and when The Evil of Frankenstein finally brought Peter Cushing's mad doctor back to the screen in 1964, it was obviously only a matter of time before the studio finally continued the story of everyone's favorite bloodsucking aristocrat. Indeed, it was almost the case that the third Dracula film would have preceded The Evil of Frankenstein; 1963's The Kiss of the Vampire was first intended as a franchise entry, but somewhere along the line it became Hammer's first stand-alone vampire picture, instead.

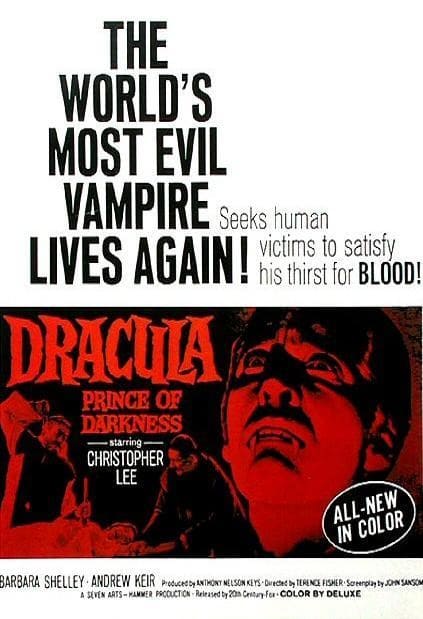

When Dracula: Prince of Darkness was ultimately released in 1966, it was received as much more of a sequel to Dracula than The Brides of Dracula ever was, for one fairly unanswerable reason: instead of centering on the further adventures of Cushing as Dr. Van Helsing, Prince of Darkness saw the return of Christopher Lee to the role that had made him a superstar. Now, who knows what goes on in the mind of Christopher Lee? I surely don't. But something happened to him in the eight years separating Dracula from its second sequel to make the actor reconsider his well-publicised fear that he was going to be typecast in the role, Lugosi-style: maybe it was the run of pirate captains and detectives and so on that he enjoyed in the first half of the decade; maybe his brief stint in the Italian film industry put the fear of God into him. At any rate, here he was, and with an uncharacteristically minimal amount of complaining about how much he hated playing vampires.

Which isn't the same as saying he didn't complain at all; apparently, he was so horrified at the dialogue he was expected to recite in this go-round that he chose instead to say nothing whatever; and as much as that story sounds like something Christopher Lee would do in the mid-'60s, I wonder. Elsewhere, director Terence Fisher and screenwriter Jimmy Sangster both suggested that they made the choice early on that Dracula was more threatening as a presence without speaking, and this seems at least as likely to me, especially given that nobody else in the picture is saddled with particularly impossible dialogue.

At any rate, just like it was in Dracula, the titular count is only in Prince of Darkness for maybe 12 minutes, tops, and it takes a good long while for him to return. The first half of the movie is given over primarily to the story of two British couples on holiday in the Carpathians: Alan Kent (Charles Tingwell) and his wife Helen (Barbara Shelley), his brother Charles (Francis Matthews), and Charles's wife Diana (Suzan Farmer). But even that doesn't start until after the film's tremendously effective opening, in which a traveling monk named Father Sandor (Andrew Kier) interrupts a funeral service deep in the woods in which the officiating priest is about to plunge a wooden stake into the body of a little girl. We know that this is a vampire movie, so we have some idea of what's going on, which is how this scene is able to tell us a great deal more than any of the characters say aloud: apparently, the fear of vampirism is still heavy in this region, despite the fact that it's been ten years since Dracula and his cult were put out of business.

When next we meet Sandor at a tiny inn where the aforementioned Kents are enjoying the local color, he needlessly confirms most of what we've already concluded. But he also makes it very clear that just because there is no present need to fear vampires, that is not to say that there is no such thing as a vampire, and his advice to the vacationing Brits is that the stay far, far away from Karlsbad - oops, that's the town they're heading to next? Well, for God's sake, don't go to the musty old castle in Karlsbad.

(Incidentally, the towns in the first Dracula were Karlstadt and Klausenberg, not Karlsbad).

The coach the travelers are taking to Karlsbad eventually drops them off near an old abandoned chateau, as the driver is hellbent on getting back to a safe town before nightfall, but almost before they can start to panic, another coach - though one without a driver, oddly enough - drives up, and over Helen's enthusiastic objections, the four tourists hop on board. Despite Charles's best attempts to steer the thing, they end up going deep into the woods, to a certain must old castle, where they find a welcoming dinner laid out by a vaguely threatening manservant, Klove (Philip Latham), who informs them that his long-dead master, Count Dracula, always wished that guests should be met with the best hospitality. Of course, we know who Dracula is, so perhaps we can excuse the rather shocking lack of concern that the Brits show for the general creepiness of everything (except, again, for Helen), as they poke into dark corners exploring. Eventually, of course, we learn that Klove isn't so concerned about providing for guests as he is anxious to get a warm-blooded body into the chamber where he's set out his master's ashes in a grim parody of a religious ceremony, and after some gore scenes that, 42 years later, have lost little of their impact (first, a very wet throat-cutting; then, a marvelous series of dissolves as the ashes reconstitute into a skeleton, then the skeleton starts to get some meat on it), we at long last get to see Lee step into the cape once more - 45 minutes into a 90 minute film.

I'd say that at this point, a second movie kicks in, but that actually takes a bit longer. First, Dracula has to menace the buxom Helen a bit, as Charles and Diana get more and more confused as to what the hell is going on. Eventually, a vampiric Helen puts the moves on Diana in a scene that must have represented, by 1966 standards, a mind-blowing level of explicit lesbianism, just before the two living Brits manage to escape to Sandor's monastery, in a masterly little bit of sleight-of-hand (how, exactly, do they know where it is?) that shows off that the difference between a good horror film and a bad horror film is mostly whether the film slows down enough to let you care about the logical inconsistencies.

And it's at the monastery that the second film begins, because all of a sudden there are a whole chunk of new characters (the most important of whom is Thorley Walters as bug-eating Ludwig, clearly based on Renfield in the novel - which, yes, means that he betrays them all to Dracula), and Sandor turns into a Van Helsing-esque vampire slayer. Naturally, it's just when everybody's guard is down that Dracula and Vampire Helen swoop in to kidnap Diana, giving Sandor and Charles the expected one single day to get back to Castle Dracula before sundown - which they fail to do, although thanks to their slowness, Prince of Darkness happens to enjoy the best climax in the whole series, as the monk figures out that there is, kind of, a way that you can kill a vampire with a rifle.

If the best part of Brides of Dracula was how it found entirely novel things to do with the well-worn tropes of a vampire movie, the chief appeal of Prince of Darkness is that it follows the standard model so very closely, but with great conviction from everyone involved. Everything you've ever seen in a vampire movie is somewhere in the film's first half: the driverless coach, the grim peasantry in the local inn, the mysterious dinner, the cryptic and terrifying manservant. In the hands of hacks, this could be a complete wreck, but Terence Fisher and Jimmy Sangster aren't just any genre filmmakers: Sangster as always brings his very literate dialogue and sly British humor, while Fisher brings a control over atmosphere that very probably leaves Prince of Darkness as the best-directed of all his vampire films (for starters, it's the first time that the film isn't mostly over-lit).

Add in Christopher Lee's return to the title role, in a performance that seems much more beastly than it did before (with much redder eye-makeup), and Prince of Darkness takes its place as perhaps Hammer's most effectively horrific Dracula movie. The first film has no end of Gothic moodiness, of course, but Peter Cushing's level presence always keeps things somewhat bright. Now, that's part of what we love about Cushing, and I'd never claim that Prince of Darkness is "better" than Dracula, or even as interesting as Brides But between the gloom, the snarling vampire, the gore, and the heroes who are clearly far out of their league, Prince of Darkness is infinitely more threatening than either of its predecessors.

That said, there are two significant problems with the movie. The first is the bit of plot leading up to the climax: it takes Charles and Diana two essentially identical attempts to make it out of Castle Dracula, which already smacks of padding out the running time; but the only word for what happens when they arrive at the monastery is "meandering". I enjoy that the film uses this opportunity to dribble out its vampiric lore instead of giving it in one heap at the start, like usually happens, but taking the time to introduce us to a whole new scenario and add a couple of characters that late into a 90 minute genre film has the tendency to drag the pace to a halt.

The other problem is the acting. Not Lee; he might have hated the character, but he's absolutely great, just as good if not a touch better than he was in Dracula (he never skips down a flight of stairs in this film for a start). And not even Andrew Kier, a Hammer stalwart who might not have been the same vampire-hunter that Peter Cushing was, but at least he's not totally out-matched by Lee's Dracula (compare in Brides, where it seemed that Van Helsing ought to be able to use that film's milquetoast vampire baddie, played by the wan David Peel, for dental floss). But the four actors playing the Kents are all pretty underwhelming - certainly proficient in the craft of acting, but hardly interesting enough to hold their own against the oppressively Gothic visuals. And we spend a lot of time in just their presence. It's the exact opposite of the problem I had in Brides, which was that only Cushing gave a particularly decent performance, but at least he dominated the whole movie.

Even with those two significant failings Prince of Darkness is an awfully good vampire movie. '66 was pretty much at the end of Hammer's Golden Age, but it's pleasing to see that even at the very cusp of its descent into self-parody and irrelevance, the studio could still produce something this satisfying from something as scattershot as the vampire subgenre.

Reviews in this series

Dracula (Fisher, 1958)

The Brides of Dracula (Fisher, 1960)

Dracula: Prince of Darkness (Fisher, 1966)

Dracula Has Risen from the Grave (Francis, 1968)

Taste the Blood of Dracula (Sasdy, 1970)

Scars of Dracula (Baker, 1970)

Dracula A.D. 1972 (Gibson, 1972)

The Satanic Rites of Dracula (Gibson, 1974)

The Legend of the 7 Golden Vampires (Baker, 1974)

When Dracula: Prince of Darkness was ultimately released in 1966, it was received as much more of a sequel to Dracula than The Brides of Dracula ever was, for one fairly unanswerable reason: instead of centering on the further adventures of Cushing as Dr. Van Helsing, Prince of Darkness saw the return of Christopher Lee to the role that had made him a superstar. Now, who knows what goes on in the mind of Christopher Lee? I surely don't. But something happened to him in the eight years separating Dracula from its second sequel to make the actor reconsider his well-publicised fear that he was going to be typecast in the role, Lugosi-style: maybe it was the run of pirate captains and detectives and so on that he enjoyed in the first half of the decade; maybe his brief stint in the Italian film industry put the fear of God into him. At any rate, here he was, and with an uncharacteristically minimal amount of complaining about how much he hated playing vampires.

Which isn't the same as saying he didn't complain at all; apparently, he was so horrified at the dialogue he was expected to recite in this go-round that he chose instead to say nothing whatever; and as much as that story sounds like something Christopher Lee would do in the mid-'60s, I wonder. Elsewhere, director Terence Fisher and screenwriter Jimmy Sangster both suggested that they made the choice early on that Dracula was more threatening as a presence without speaking, and this seems at least as likely to me, especially given that nobody else in the picture is saddled with particularly impossible dialogue.

At any rate, just like it was in Dracula, the titular count is only in Prince of Darkness for maybe 12 minutes, tops, and it takes a good long while for him to return. The first half of the movie is given over primarily to the story of two British couples on holiday in the Carpathians: Alan Kent (Charles Tingwell) and his wife Helen (Barbara Shelley), his brother Charles (Francis Matthews), and Charles's wife Diana (Suzan Farmer). But even that doesn't start until after the film's tremendously effective opening, in which a traveling monk named Father Sandor (Andrew Kier) interrupts a funeral service deep in the woods in which the officiating priest is about to plunge a wooden stake into the body of a little girl. We know that this is a vampire movie, so we have some idea of what's going on, which is how this scene is able to tell us a great deal more than any of the characters say aloud: apparently, the fear of vampirism is still heavy in this region, despite the fact that it's been ten years since Dracula and his cult were put out of business.

When next we meet Sandor at a tiny inn where the aforementioned Kents are enjoying the local color, he needlessly confirms most of what we've already concluded. But he also makes it very clear that just because there is no present need to fear vampires, that is not to say that there is no such thing as a vampire, and his advice to the vacationing Brits is that the stay far, far away from Karlsbad - oops, that's the town they're heading to next? Well, for God's sake, don't go to the musty old castle in Karlsbad.

(Incidentally, the towns in the first Dracula were Karlstadt and Klausenberg, not Karlsbad).

The coach the travelers are taking to Karlsbad eventually drops them off near an old abandoned chateau, as the driver is hellbent on getting back to a safe town before nightfall, but almost before they can start to panic, another coach - though one without a driver, oddly enough - drives up, and over Helen's enthusiastic objections, the four tourists hop on board. Despite Charles's best attempts to steer the thing, they end up going deep into the woods, to a certain must old castle, where they find a welcoming dinner laid out by a vaguely threatening manservant, Klove (Philip Latham), who informs them that his long-dead master, Count Dracula, always wished that guests should be met with the best hospitality. Of course, we know who Dracula is, so perhaps we can excuse the rather shocking lack of concern that the Brits show for the general creepiness of everything (except, again, for Helen), as they poke into dark corners exploring. Eventually, of course, we learn that Klove isn't so concerned about providing for guests as he is anxious to get a warm-blooded body into the chamber where he's set out his master's ashes in a grim parody of a religious ceremony, and after some gore scenes that, 42 years later, have lost little of their impact (first, a very wet throat-cutting; then, a marvelous series of dissolves as the ashes reconstitute into a skeleton, then the skeleton starts to get some meat on it), we at long last get to see Lee step into the cape once more - 45 minutes into a 90 minute film.

I'd say that at this point, a second movie kicks in, but that actually takes a bit longer. First, Dracula has to menace the buxom Helen a bit, as Charles and Diana get more and more confused as to what the hell is going on. Eventually, a vampiric Helen puts the moves on Diana in a scene that must have represented, by 1966 standards, a mind-blowing level of explicit lesbianism, just before the two living Brits manage to escape to Sandor's monastery, in a masterly little bit of sleight-of-hand (how, exactly, do they know where it is?) that shows off that the difference between a good horror film and a bad horror film is mostly whether the film slows down enough to let you care about the logical inconsistencies.

And it's at the monastery that the second film begins, because all of a sudden there are a whole chunk of new characters (the most important of whom is Thorley Walters as bug-eating Ludwig, clearly based on Renfield in the novel - which, yes, means that he betrays them all to Dracula), and Sandor turns into a Van Helsing-esque vampire slayer. Naturally, it's just when everybody's guard is down that Dracula and Vampire Helen swoop in to kidnap Diana, giving Sandor and Charles the expected one single day to get back to Castle Dracula before sundown - which they fail to do, although thanks to their slowness, Prince of Darkness happens to enjoy the best climax in the whole series, as the monk figures out that there is, kind of, a way that you can kill a vampire with a rifle.

If the best part of Brides of Dracula was how it found entirely novel things to do with the well-worn tropes of a vampire movie, the chief appeal of Prince of Darkness is that it follows the standard model so very closely, but with great conviction from everyone involved. Everything you've ever seen in a vampire movie is somewhere in the film's first half: the driverless coach, the grim peasantry in the local inn, the mysterious dinner, the cryptic and terrifying manservant. In the hands of hacks, this could be a complete wreck, but Terence Fisher and Jimmy Sangster aren't just any genre filmmakers: Sangster as always brings his very literate dialogue and sly British humor, while Fisher brings a control over atmosphere that very probably leaves Prince of Darkness as the best-directed of all his vampire films (for starters, it's the first time that the film isn't mostly over-lit).

Add in Christopher Lee's return to the title role, in a performance that seems much more beastly than it did before (with much redder eye-makeup), and Prince of Darkness takes its place as perhaps Hammer's most effectively horrific Dracula movie. The first film has no end of Gothic moodiness, of course, but Peter Cushing's level presence always keeps things somewhat bright. Now, that's part of what we love about Cushing, and I'd never claim that Prince of Darkness is "better" than Dracula, or even as interesting as Brides But between the gloom, the snarling vampire, the gore, and the heroes who are clearly far out of their league, Prince of Darkness is infinitely more threatening than either of its predecessors.

That said, there are two significant problems with the movie. The first is the bit of plot leading up to the climax: it takes Charles and Diana two essentially identical attempts to make it out of Castle Dracula, which already smacks of padding out the running time; but the only word for what happens when they arrive at the monastery is "meandering". I enjoy that the film uses this opportunity to dribble out its vampiric lore instead of giving it in one heap at the start, like usually happens, but taking the time to introduce us to a whole new scenario and add a couple of characters that late into a 90 minute genre film has the tendency to drag the pace to a halt.

The other problem is the acting. Not Lee; he might have hated the character, but he's absolutely great, just as good if not a touch better than he was in Dracula (he never skips down a flight of stairs in this film for a start). And not even Andrew Kier, a Hammer stalwart who might not have been the same vampire-hunter that Peter Cushing was, but at least he's not totally out-matched by Lee's Dracula (compare in Brides, where it seemed that Van Helsing ought to be able to use that film's milquetoast vampire baddie, played by the wan David Peel, for dental floss). But the four actors playing the Kents are all pretty underwhelming - certainly proficient in the craft of acting, but hardly interesting enough to hold their own against the oppressively Gothic visuals. And we spend a lot of time in just their presence. It's the exact opposite of the problem I had in Brides, which was that only Cushing gave a particularly decent performance, but at least he dominated the whole movie.

Even with those two significant failings Prince of Darkness is an awfully good vampire movie. '66 was pretty much at the end of Hammer's Golden Age, but it's pleasing to see that even at the very cusp of its descent into self-parody and irrelevance, the studio could still produce something this satisfying from something as scattershot as the vampire subgenre.

Reviews in this series

Dracula (Fisher, 1958)

The Brides of Dracula (Fisher, 1960)

Dracula: Prince of Darkness (Fisher, 1966)

Dracula Has Risen from the Grave (Francis, 1968)

Taste the Blood of Dracula (Sasdy, 1970)

Scars of Dracula (Baker, 1970)

Dracula A.D. 1972 (Gibson, 1972)

The Satanic Rites of Dracula (Gibson, 1974)

The Legend of the 7 Golden Vampires (Baker, 1974)

Categories: british cinema, hammer films, horror, vampires