The 44th Chicago International Film Festival

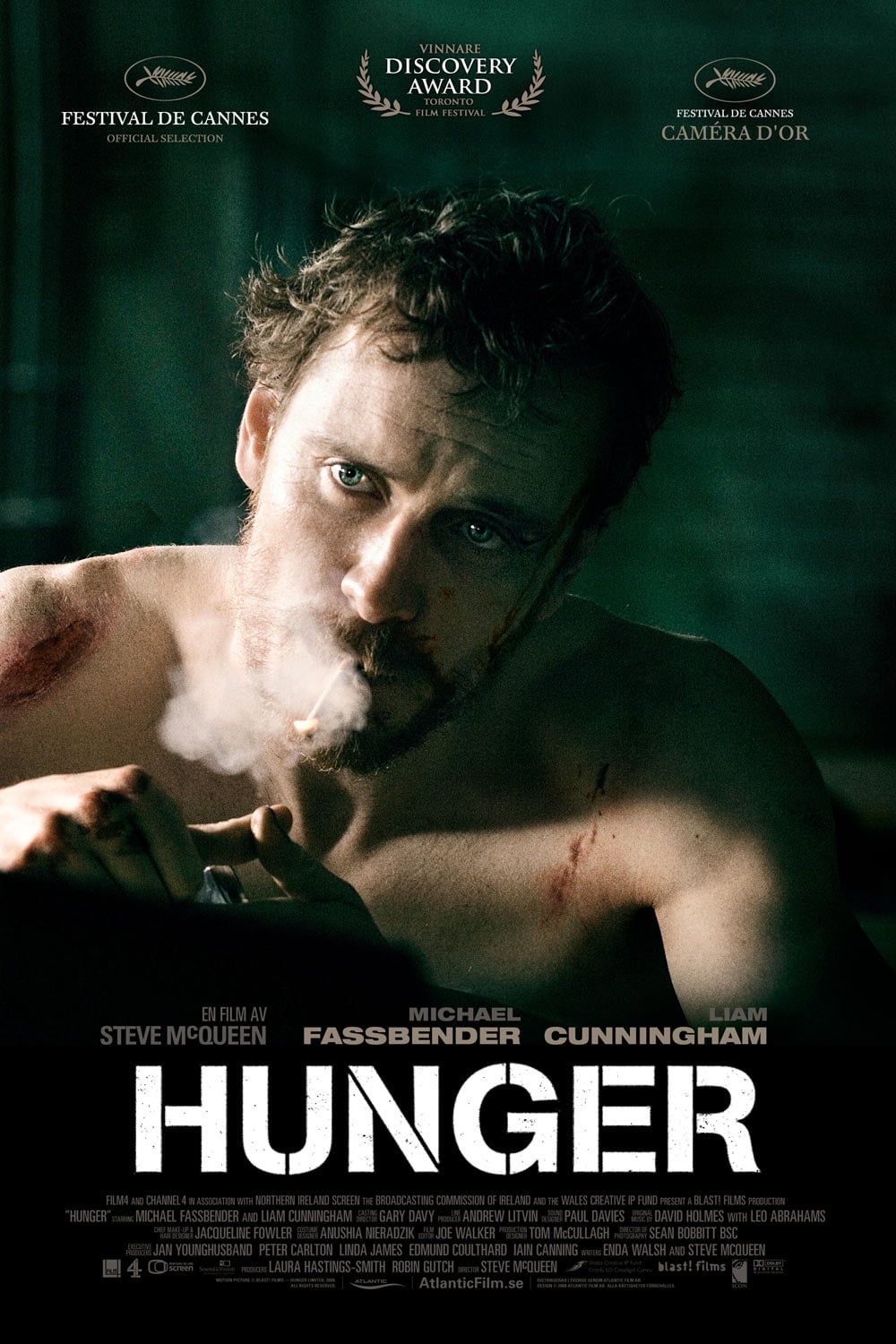

Winner of the 2008 Camera d'Or at Cannes, Hunger, the first proper narrative feature directed by British artist Steve McQueen, is without question one of the most self-assured first films to come out in ages - among the best debuts for an English-language filmmaker in this decade, along with David Gordon Green's George Washington and Sarah Polley's Away from Her. The film is one of the most brutal, devastating things I have seen in long time, and I cannot imagine that a more seasoned director would have been able to improve upon it; indeed, my suspicion is that a seasoned director would have shied away from making a movie so wholly joyless and punishing.

Hunger tells the true story of IRA fighter Bobby Sands, who organised the 1981 hunger strike against the Thatcher government's refusal to recognise Irish Republican terrorists with the status of political prisoners. Sands died after being elected Member of Parliament, one of ten men who died during the strike which ultimately resulted in the British government giving in to the IRA demands in the face of massive international support.

Sands doesn't appear for almost one-third of the film, which begins by showing the horrible conditions of HM Prison Maze (locally known as Long Kesh) during the "dirty strike" preceding the hunger strike, in which IRA prisoners were encouraged to smear the walls of their cells with feces and refuse to bathe themselves. As Hunger opens, we're introduced to Ray Lohan (Stuart Graham), a guard stationed at Long Kesh, whose day begins with breakfast, kissing the wife goodbye, and checking underneath his car for bombs (the moment when he turns on the ignition, less than five minutes into the film, is the first of what will be many moments of horribly unbearable tension). Then we meet new prisoner Davey (Brian Milligan), who refuses to put on a prisoner's uniform and as a result is left with nothing but a raggedy towel to tie around his waste (this was part of the Irish protest strategy at the time). His cellmate is Gerry (Liam McMahon), who has already done the hard work of crapping up the cell, and it's through these two that we'll see most of the film's most brutal images, as the guards repeatedly harass, humiliate and beat the prisoners, including Lohan, who obviously has strong reservations about what the Brits are doing to their charges, but joins in without hesitation when the time comes.

The first half-hour of Hunger looks a whole lot like torture porn without the exploitation or leering tone: a parade of horrors laid upon the human frame that you'd never think it could survive (except of course, that many hundreds of prisoners survived exactly this during the Troubles). Even so, the final sequence is somehow, even worse: having been earlier introduced to Sands (Michael Fassbender), we are invited to watch as, over a period of 66 days, the prisoner starves himself to death. Fassbender went on a carefully-monitored crash diet to whittle himself to a cadaverous thinness, and just that would be thoroughly terrifying, but then there's the little matter of the make-up (dear God, I hope it's make-up) used to give him bedsores and lesions and other ugly, oozing side-effects of forcing your body to survive on water and the occasional force saline drip.

McQueen never sensationalises his material, letting the depravities depicted onscreen talk for themselves, using a very direct documentary-style language to shoot the film. Hunger is primarily a film of very long takes, very few of which (if any) are hand-held: so when for example we're watching a cluster of guards beating the life out of prisoners, the camera is right up close to them, but except for the odd pan across the carnage, or dolly over to the side, the perspective doesn't really move. The endlessly long shots that make up the film start to pick up an abstract beauty that contrasts the on-screen action well, making a film that is much a meditation on violence as an exposé.

This style reaches its apogee in the film's least-typical but most-discussed scene: a ten-minute single-take conversation between Sands and his priest, Father Moran (Liam Cunningham), discussing the morality of what Sands is about to undertake. Two men sitting at a table in a static two-shot, the only real action in the frame being the undulation of cigarette smoke: that is the kind of statement that a director can only make if he is wholly sure of his material, and McQueen's gamble pays of in a tremendously successful scene. It gives the audience a bit of a breather from the horrors past and the horrors to come, it presents the film's theme in a compact form to be decoded later, once the issues at play have been seen and not merely theorised, and it gives the film the only brief flashes of what possibly be defended as "humor".

Now, all of that is undeniably strong stuff, but - just to play devil's advocate - it's obvious that you can take the artist out of the installation piece, but you can't take the installation piece out of the artist. By which I mean, though he can craft a truly harrowing scene in the here and now, McQueen (who co-wrote the screenplay with Irish playwright Enda Walsh) isn't a tremendously great storyteller. The narrative of Hunger is a perplexing and often messy thing, leaving some threads dropped entirely (Gerry and Davey are dropped entirely) or underdeveloped (the ultimate fate of Roy Lohan is stuffed into the film without fanfare). Perhaps as a result - perhaps just accidentally - the characters aren't fully developed themselves, ending up as things that actions happen to, rather than persons in their own right (notwithstanding that 10-minute ethical debate). Compare Fassbender's emaciation to Christian Bale's similar work in The Machinist, and it's hard not to conclude that getting thin is the entirety of Fassbender's performance; in no other way does he really bring Bobby Sands to life, because Bobby Sands, in the film, is nothing but an icon.

I bring these issues up only to ignore them, for I can imagine no way to address these "problems" without making Hunger a very different and almost certainly lesser work. As it stands, it's perfect as a depiction of a living hell, and only nearly perfect in explaining the human dimensions of that hell. It's probably more of an intellectual exercise than a complete movie, but would that all intellectual exercises had this much emotional power behind them.

Hunger tells the true story of IRA fighter Bobby Sands, who organised the 1981 hunger strike against the Thatcher government's refusal to recognise Irish Republican terrorists with the status of political prisoners. Sands died after being elected Member of Parliament, one of ten men who died during the strike which ultimately resulted in the British government giving in to the IRA demands in the face of massive international support.

Sands doesn't appear for almost one-third of the film, which begins by showing the horrible conditions of HM Prison Maze (locally known as Long Kesh) during the "dirty strike" preceding the hunger strike, in which IRA prisoners were encouraged to smear the walls of their cells with feces and refuse to bathe themselves. As Hunger opens, we're introduced to Ray Lohan (Stuart Graham), a guard stationed at Long Kesh, whose day begins with breakfast, kissing the wife goodbye, and checking underneath his car for bombs (the moment when he turns on the ignition, less than five minutes into the film, is the first of what will be many moments of horribly unbearable tension). Then we meet new prisoner Davey (Brian Milligan), who refuses to put on a prisoner's uniform and as a result is left with nothing but a raggedy towel to tie around his waste (this was part of the Irish protest strategy at the time). His cellmate is Gerry (Liam McMahon), who has already done the hard work of crapping up the cell, and it's through these two that we'll see most of the film's most brutal images, as the guards repeatedly harass, humiliate and beat the prisoners, including Lohan, who obviously has strong reservations about what the Brits are doing to their charges, but joins in without hesitation when the time comes.

The first half-hour of Hunger looks a whole lot like torture porn without the exploitation or leering tone: a parade of horrors laid upon the human frame that you'd never think it could survive (except of course, that many hundreds of prisoners survived exactly this during the Troubles). Even so, the final sequence is somehow, even worse: having been earlier introduced to Sands (Michael Fassbender), we are invited to watch as, over a period of 66 days, the prisoner starves himself to death. Fassbender went on a carefully-monitored crash diet to whittle himself to a cadaverous thinness, and just that would be thoroughly terrifying, but then there's the little matter of the make-up (dear God, I hope it's make-up) used to give him bedsores and lesions and other ugly, oozing side-effects of forcing your body to survive on water and the occasional force saline drip.

McQueen never sensationalises his material, letting the depravities depicted onscreen talk for themselves, using a very direct documentary-style language to shoot the film. Hunger is primarily a film of very long takes, very few of which (if any) are hand-held: so when for example we're watching a cluster of guards beating the life out of prisoners, the camera is right up close to them, but except for the odd pan across the carnage, or dolly over to the side, the perspective doesn't really move. The endlessly long shots that make up the film start to pick up an abstract beauty that contrasts the on-screen action well, making a film that is much a meditation on violence as an exposé.

This style reaches its apogee in the film's least-typical but most-discussed scene: a ten-minute single-take conversation between Sands and his priest, Father Moran (Liam Cunningham), discussing the morality of what Sands is about to undertake. Two men sitting at a table in a static two-shot, the only real action in the frame being the undulation of cigarette smoke: that is the kind of statement that a director can only make if he is wholly sure of his material, and McQueen's gamble pays of in a tremendously successful scene. It gives the audience a bit of a breather from the horrors past and the horrors to come, it presents the film's theme in a compact form to be decoded later, once the issues at play have been seen and not merely theorised, and it gives the film the only brief flashes of what possibly be defended as "humor".

Now, all of that is undeniably strong stuff, but - just to play devil's advocate - it's obvious that you can take the artist out of the installation piece, but you can't take the installation piece out of the artist. By which I mean, though he can craft a truly harrowing scene in the here and now, McQueen (who co-wrote the screenplay with Irish playwright Enda Walsh) isn't a tremendously great storyteller. The narrative of Hunger is a perplexing and often messy thing, leaving some threads dropped entirely (Gerry and Davey are dropped entirely) or underdeveloped (the ultimate fate of Roy Lohan is stuffed into the film without fanfare). Perhaps as a result - perhaps just accidentally - the characters aren't fully developed themselves, ending up as things that actions happen to, rather than persons in their own right (notwithstanding that 10-minute ethical debate). Compare Fassbender's emaciation to Christian Bale's similar work in The Machinist, and it's hard not to conclude that getting thin is the entirety of Fassbender's performance; in no other way does he really bring Bobby Sands to life, because Bobby Sands, in the film, is nothing but an icon.

I bring these issues up only to ignore them, for I can imagine no way to address these "problems" without making Hunger a very different and almost certainly lesser work. As it stands, it's perfect as a depiction of a living hell, and only nearly perfect in explaining the human dimensions of that hell. It's probably more of an intellectual exercise than a complete movie, but would that all intellectual exercises had this much emotional power behind them.

Categories: british cinema, ciff, incredibly unpleasant films, irish cinema, violence and gore