The 44th Chicago International Film Festival

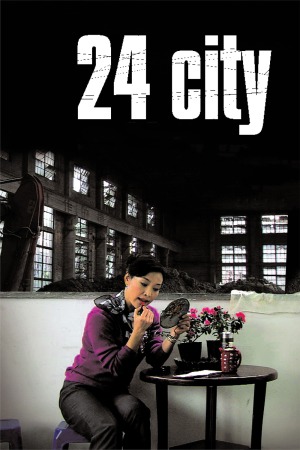

A slightly embarrassing confession: despite his reputation as one of the pre-eminent Chinese filmmakers of the current century, I've had some difficulty in the past "getting" the work of Jia Zhang-Ke, at least those films I've seen. To my eyes, his big breakthrough, 2000's Platform, is an exceptionally over-praised work of no particular merit, while Unknown Pleasures and The World justified much more of the breathless praise that greeted them in this country, though both felt a little "overdetermined" to me, assembled perfectly but with a chilly reserve that kept them from meaning a whole lot outside "I'm Jia Zhang-Ke, and I have a tremendously disciplined control over where to set my camera". Still Life was a huge stride towards making a film that wasn't just a formally flawless intellectual puzzle, but it's with his new 24 City that Jia has finally made a film that I'm perfectly happy to call one of the year's best. I'd better avoid making too many blanket statements without having seen all of the director's films - in particular, his well-regarded 2006 documentary Dong - but as far as I'm concerned, 24 City is his first masterpiece.

Like Still Life, a narrative film masquerading as a documentary, and more of an essay on the status of life in a modernising China than either, 24 City is structured as a series of interviews with the current and former employees of Factory 420 in Chengdu, a former aeronautics factory being shut down and relocated to make room for a glitzy new residential community called 24 City. These interviews are intercut with what we might call Chengdu b-roll: panoramas of the city, or footage of the interviewees going on about their life for a little bit.

It becomes clear sooner or later than Jia's not being entirely forthcoming with us, and while many of the interviews are the actual men and women of Factory 420, some of them are actors playing roles. The filmmaker tips his hand in an arch moment in which famed Chinese actress Joan Chen plays a retiring worker nicknamed "Little Flower", a name given to her because back in the early '80s, everybody thought she looked like Joan Chen in Little Flower. That's a bold move for the film to make, and for plenty of people the winking games Jia plays with reality are proof enough that 24 City isn't up to his best work.

I'd argue that on the contrary, Jia is well aware that by pulling the rug from underneath us, he's making it very hard to completely engage with his story about Factory 420, and I think that in a Brechtian way that's exactly what he wants. Thanks to its documentary structure, 24 City seems like it's supposed to be the story of a specific place from its secret birth to its death, but in bragging about how parts of it are real and parts are made up, and he's not telling us which, Jia invalidates that movie. In its place, 24 City the semi-fictional construct is a story about China since Mao, attempting in less than two hours to cover a remarkably wide swath of modern Chinese society, and coming up with a film that's often startlingly free in its criticism of the country's current government. I have no idea whatsoever if Jia in his personal life is a Marxist or Maoist or free-market libertarian, but 24 City is essentially an argument that the modernisation of China has been accompanied by the abandonment of everything Marxist or Leninist about the original revolution in favor of a destructive capitalist/Maoist hybrid that's not really like any coherent political or economic school that has ever been described on Earth.

The interviews, representing a suspiciously comprehensive cross-section of demographics, all tend to revolve around the idea that the way things were was generally an improvement over the way things are; sometimes it's an old-timer saying that outright or implying it, and sometimes it's just the vapid way that the younger generation seems oblivious to anything but their own needs (the air-headed young lady that ends the film - I'm fairly certain she must be an actress - seems a bit oblivious that there is this thing called "history" at all). But it's within what I've called the "b-roll" that 24 City really pokes at this idea, sometimes in tremendously subtle ways. The scene that sums up the whole movie for me comes when a group of older workers end their day with a group sing-along to "The International": but the tinkly synthesised version of that anthem that they're singing with is so thin as to be a parody of left-wing fervor. So it goes with all of the film: whatever China is, it's not remotely what the revolutionaries in the 1940s said it was going to be.

Whether Jia staged this part or that of the film ultimately doesn't matter, given that either way he's using Factory 420 as a metaphor for a neo-capitalist China that's devouring its own history. What use does a metaphor have for accurate reportage, anyway? The film that results may tell less of a human-sized story than any of Jia's previous work, and this may be a disappointment to those who felt that the human element of his films was a bigger draw than I ever have, but I'll happily take the large-scale sociology of 24 City any day. Divide it from its culturally specific trappings, and what we've got left is a film arguing as persuasively as I've ever seen it argued that "progress" is what happens when people start to forget what history looked like. A cautionary, even reactionary theme, but it's good to be reminded from time to time what happens to people who forget about history.

10/10

Like Still Life, a narrative film masquerading as a documentary, and more of an essay on the status of life in a modernising China than either, 24 City is structured as a series of interviews with the current and former employees of Factory 420 in Chengdu, a former aeronautics factory being shut down and relocated to make room for a glitzy new residential community called 24 City. These interviews are intercut with what we might call Chengdu b-roll: panoramas of the city, or footage of the interviewees going on about their life for a little bit.

It becomes clear sooner or later than Jia's not being entirely forthcoming with us, and while many of the interviews are the actual men and women of Factory 420, some of them are actors playing roles. The filmmaker tips his hand in an arch moment in which famed Chinese actress Joan Chen plays a retiring worker nicknamed "Little Flower", a name given to her because back in the early '80s, everybody thought she looked like Joan Chen in Little Flower. That's a bold move for the film to make, and for plenty of people the winking games Jia plays with reality are proof enough that 24 City isn't up to his best work.

I'd argue that on the contrary, Jia is well aware that by pulling the rug from underneath us, he's making it very hard to completely engage with his story about Factory 420, and I think that in a Brechtian way that's exactly what he wants. Thanks to its documentary structure, 24 City seems like it's supposed to be the story of a specific place from its secret birth to its death, but in bragging about how parts of it are real and parts are made up, and he's not telling us which, Jia invalidates that movie. In its place, 24 City the semi-fictional construct is a story about China since Mao, attempting in less than two hours to cover a remarkably wide swath of modern Chinese society, and coming up with a film that's often startlingly free in its criticism of the country's current government. I have no idea whatsoever if Jia in his personal life is a Marxist or Maoist or free-market libertarian, but 24 City is essentially an argument that the modernisation of China has been accompanied by the abandonment of everything Marxist or Leninist about the original revolution in favor of a destructive capitalist/Maoist hybrid that's not really like any coherent political or economic school that has ever been described on Earth.

The interviews, representing a suspiciously comprehensive cross-section of demographics, all tend to revolve around the idea that the way things were was generally an improvement over the way things are; sometimes it's an old-timer saying that outright or implying it, and sometimes it's just the vapid way that the younger generation seems oblivious to anything but their own needs (the air-headed young lady that ends the film - I'm fairly certain she must be an actress - seems a bit oblivious that there is this thing called "history" at all). But it's within what I've called the "b-roll" that 24 City really pokes at this idea, sometimes in tremendously subtle ways. The scene that sums up the whole movie for me comes when a group of older workers end their day with a group sing-along to "The International": but the tinkly synthesised version of that anthem that they're singing with is so thin as to be a parody of left-wing fervor. So it goes with all of the film: whatever China is, it's not remotely what the revolutionaries in the 1940s said it was going to be.

Whether Jia staged this part or that of the film ultimately doesn't matter, given that either way he's using Factory 420 as a metaphor for a neo-capitalist China that's devouring its own history. What use does a metaphor have for accurate reportage, anyway? The film that results may tell less of a human-sized story than any of Jia's previous work, and this may be a disappointment to those who felt that the human element of his films was a bigger draw than I ever have, but I'll happily take the large-scale sociology of 24 City any day. Divide it from its culturally specific trappings, and what we've got left is a film arguing as persuasively as I've ever seen it argued that "progress" is what happens when people start to forget what history looked like. A cautionary, even reactionary theme, but it's good to be reminded from time to time what happens to people who forget about history.

10/10