They Shoot Pictures, Don't They? 2008 Edition - #472

Scholarship is a living, breathing animal. Go back a few years - not that many, maybe not even a full decade - and you'll find this conventional wisdom about the rise of European "Art Cinema" in the 1950s: Ingmar Bergman, master of the form, burst out fully formed with his 17th and 18th features, The Seventh Seal and Wild Strawberries. Skip ahead a year or two, though, and a different story begins to reveal itself: no, the first major Bergman film was Smiles of a Summer Night, which although a comedy was the first time that Bergman's dark psychological concerns were presented in their full form. Skip a couple of years later, and the new emerging consensus that seems to have been cemented by the director's death last summer: the first actual Bergman movie was our current subject, 1953's Sawdust and Tinsel, his 13th film as director and the moment where he made the great stylistic breakthrough that would forever after define "Bergmanesque."

Setting aside the fact that all of these post-date his actual breakthrough outside of Sweden, Summer with Monika, which was marketed internationally through the mid-'50s as being the raciest thing you ever did see, and drew in the crowds you'd expect that claim to draw, Sawdust and Tinsel seems to be as good a place as any to mark the point where the well-meaning but clumsy director of downer chamber dramas like Crisis and A Ship to India turned into the self-assured master behind miserable chamber dramas like The Silence and Cries and Whispers. The reason, I think, has little to do with the subject matter - it's certainly characteristic, but not hugely different from a lot of what he'd already done - and more to do with the great collaborator whom Bergman first worked with on this project: cinematographer Sven Nykvist.

It's a bit dangerous to talk about such things, particularly given the weird way that directors and DPs interact on a film set, but I'd be more than a little bit tempted to call the three-decade relationship between Bergman and Nykvist - Bergvist? - the richest such pairing in the history of cinema. It can hardly be an accident that all but a tiny handful of the films typically cited as Bergman's masterpieces were shot by Nykvist; they complemented each other like few artistic collaborations ever had. It was thanks to Nykvist, I think, that Bergman was able to perfect the single stylstic flourish most readily associated with his films: enveloping, awe-inspiring close-ups of men and women in torment. Obviously, many filmmakers have used close-ups, but it was in the Bergvist films that this well-traveled little compositional tool reached its finest expression in the sound cinema. That has a lot to do with the actors Bergman favored, I have no doubt, but it's not such an easy matter to point a camera at even a flawless performance and expect that magic happens. It takes superhuman control of lighting and focus to make a close-up truly devastating, and these two men made that happen again and again - culminating, I'd argue, in Scenes from a Marriage, a five-hour masterpiece that seems to consist of virtually nothing but close-ups, and is the second-greatest movie made in that idiom after only Dreyer's The Passion of Joan of Arc.

And it was in Sawdust and Tinsel, so far as I can make out, that Bergman perfected the art of the close-up. It is true that Nykvist was not alone in shooting the film - he shared credit with Hilding Bladh, in the second of three films he made with the director - but it's telling, I think, that his most famous trick should be used to such great effect here. Faces are how the story and conflicts are expressed - oh, sure, dialogue helps, and it's that wonderfully arch dialogue that Bergman always favored and really started to perfect in the early 1960s. But the most intense and harrowing moments - I am particularly thinking of a shot late in the film from inside a cage, looking out at the protagonist between bars - are carried on the wide eyes and sweaty flesh of the characters, enough so that Sawdust and Tinsel could work nearly as well as a silent film.

Outside of this obsession with faces, there are plenty of moments and shots which anticipate Bergman's later films: famously the opening shot, which is replicated almost at the very end, is essentially a mirror of the iconic "Dance with Death" shot from The Seventh Seal; an extended flashback is shot in a deliberately over-exposed fashion that makes it seem unreal and dreamlike, calling to mind the dream sequences in Wild Strawberries. But Sawdust and Tinsel isn't just a showcase for motifs that Bergman would use to create masterpieces later; it's a great film all by itself, using that imagery just as well as its successors would.

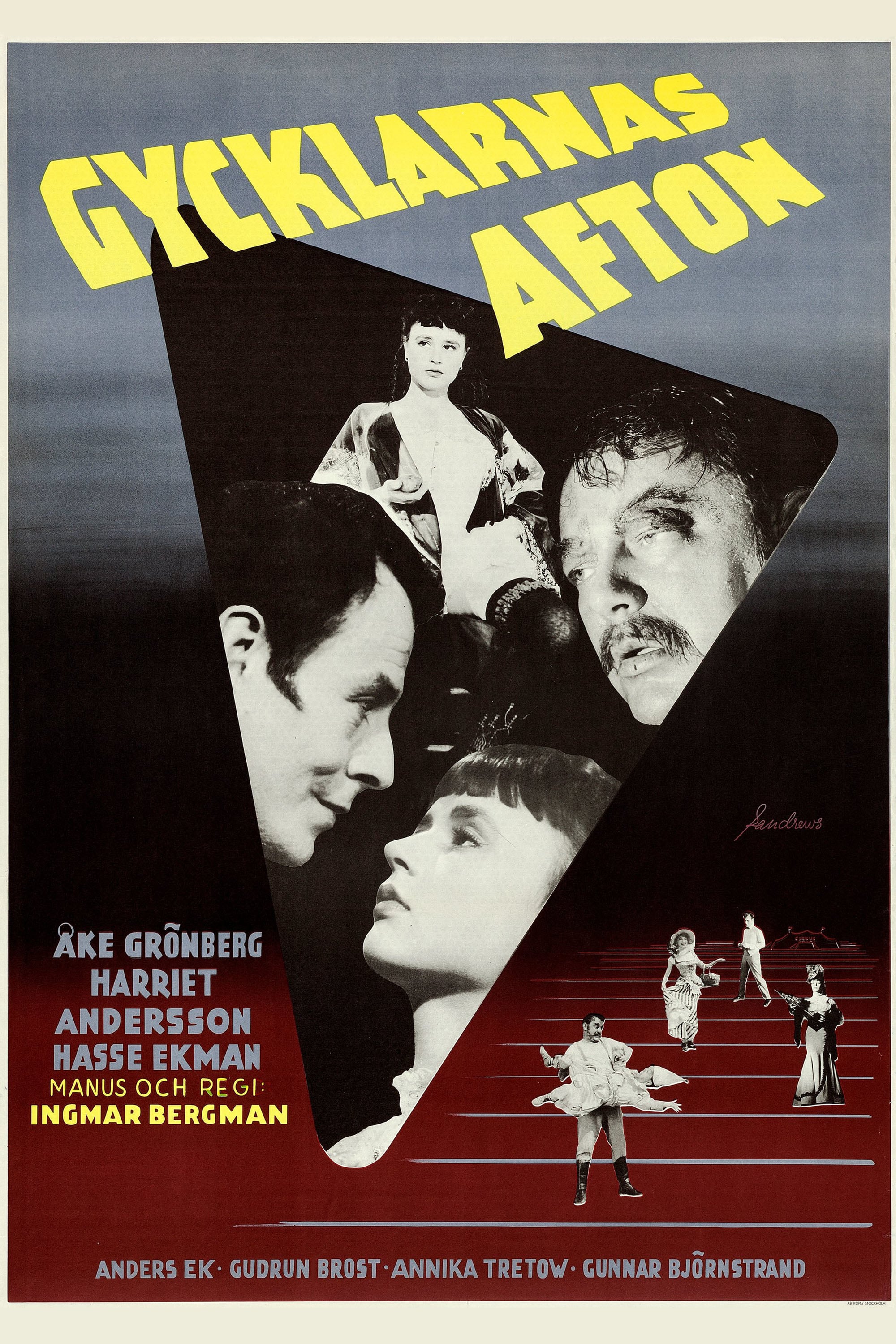

The film concerns a traveling circus troupe owned and managed by Albert Johansson (Åke Grönberg), who left his wife and children many years earlier to pursue the life of a showman and take as his lover an equestrian performer, Anne (Bergman regular Harriet Andersson). Over the course of two very long days, as Albert finally concludes that he will never make a penny from running a circus, jealousy starts to crack at his relationship with Anne, mirroring a half-remembered story told about the clown Frost (Anders Ek) and his wife Agda (Annika Tretow), and the old canard about how "the show must go on" starts to feel increasingly labored as men, horses, and dancing bears all start to suffer from the effects of a life without food or shelter.

Delicately layered, but far easier than most of Bergman's later films (compared even to Smiles of a Summer Night or The Seventh Seal, it's terrifically straightforward), Sawdust and Tinsel is basically a fable about how dreams die and how the grinding needs of life outweigh such niceties as ideals and love (the original Swedish title translates loosely as "The Clown's Evening", but I'd reckon that the English title is far more expressive, reducing the magic of the circus to cheap trappings - sawdust and tinsel are both the stuff of the performance, and the trash lying in the gutter when the performance ends). A perfectly Bergmanesque sentiment, then, and one that lies far removed from how e.g. Fellini might have treated the same matter. Not an idle comparison; Sadust and Tinsel is more than a bit reminiscent of La strada or Variety Lights, Fellini's collaboration with Alberto Lattuada, and of course the Italian filmmaker's career is positively riddled with clowns; but where Fellini would have privileged the humane quality of the story, even the idea that performers are a family who need love just like anybody, Bergman is strictly focused on his characters' degradations - and in this, too, Sawdust and Tinsel looks ahead to his future work.

One of the key moments in the film comes when Albert goes to beg help from Sjuberg (Gunnar Björnstrand), the director of a rag-tag theater troupe. Sjuberg rebuffs him, and in a strangely angry moment declares that actors put themselves to greater danger than circus performers; since the carnies only risk their lives, while actors risk their pride. As a statement of artistic principals, that's a straightforward idea which we could debate for days, but within the film, it has another clear meaning: Albert and his crew must risk their lives because they have no pride left - by the time we meet them, a lifetime of humiliations has all but destroyed the human dignity they ever possessed.

Strange for a filmmaker who professed until the end of his life that theater was his first and truest love to make a film - his first set in the world of performing arts - that would go to such lengths to make it seem that theatrical performers (on stage, under the tent) suffer horrid degradations and lead miserable lives; but then again, he was Ingmar Bergman, a man who never stopped fixating on the amount of suffering humans could withstand, nor on those humans ability or inability to survive that suffering and emerge with their souls intact. Sawdust and Tinsel is neither his most miserable nor his most humane film, but in this as well as everything else, it is a tremendous first step.

Setting aside the fact that all of these post-date his actual breakthrough outside of Sweden, Summer with Monika, which was marketed internationally through the mid-'50s as being the raciest thing you ever did see, and drew in the crowds you'd expect that claim to draw, Sawdust and Tinsel seems to be as good a place as any to mark the point where the well-meaning but clumsy director of downer chamber dramas like Crisis and A Ship to India turned into the self-assured master behind miserable chamber dramas like The Silence and Cries and Whispers. The reason, I think, has little to do with the subject matter - it's certainly characteristic, but not hugely different from a lot of what he'd already done - and more to do with the great collaborator whom Bergman first worked with on this project: cinematographer Sven Nykvist.

It's a bit dangerous to talk about such things, particularly given the weird way that directors and DPs interact on a film set, but I'd be more than a little bit tempted to call the three-decade relationship between Bergman and Nykvist - Bergvist? - the richest such pairing in the history of cinema. It can hardly be an accident that all but a tiny handful of the films typically cited as Bergman's masterpieces were shot by Nykvist; they complemented each other like few artistic collaborations ever had. It was thanks to Nykvist, I think, that Bergman was able to perfect the single stylstic flourish most readily associated with his films: enveloping, awe-inspiring close-ups of men and women in torment. Obviously, many filmmakers have used close-ups, but it was in the Bergvist films that this well-traveled little compositional tool reached its finest expression in the sound cinema. That has a lot to do with the actors Bergman favored, I have no doubt, but it's not such an easy matter to point a camera at even a flawless performance and expect that magic happens. It takes superhuman control of lighting and focus to make a close-up truly devastating, and these two men made that happen again and again - culminating, I'd argue, in Scenes from a Marriage, a five-hour masterpiece that seems to consist of virtually nothing but close-ups, and is the second-greatest movie made in that idiom after only Dreyer's The Passion of Joan of Arc.

And it was in Sawdust and Tinsel, so far as I can make out, that Bergman perfected the art of the close-up. It is true that Nykvist was not alone in shooting the film - he shared credit with Hilding Bladh, in the second of three films he made with the director - but it's telling, I think, that his most famous trick should be used to such great effect here. Faces are how the story and conflicts are expressed - oh, sure, dialogue helps, and it's that wonderfully arch dialogue that Bergman always favored and really started to perfect in the early 1960s. But the most intense and harrowing moments - I am particularly thinking of a shot late in the film from inside a cage, looking out at the protagonist between bars - are carried on the wide eyes and sweaty flesh of the characters, enough so that Sawdust and Tinsel could work nearly as well as a silent film.

Outside of this obsession with faces, there are plenty of moments and shots which anticipate Bergman's later films: famously the opening shot, which is replicated almost at the very end, is essentially a mirror of the iconic "Dance with Death" shot from The Seventh Seal; an extended flashback is shot in a deliberately over-exposed fashion that makes it seem unreal and dreamlike, calling to mind the dream sequences in Wild Strawberries. But Sawdust and Tinsel isn't just a showcase for motifs that Bergman would use to create masterpieces later; it's a great film all by itself, using that imagery just as well as its successors would.

The film concerns a traveling circus troupe owned and managed by Albert Johansson (Åke Grönberg), who left his wife and children many years earlier to pursue the life of a showman and take as his lover an equestrian performer, Anne (Bergman regular Harriet Andersson). Over the course of two very long days, as Albert finally concludes that he will never make a penny from running a circus, jealousy starts to crack at his relationship with Anne, mirroring a half-remembered story told about the clown Frost (Anders Ek) and his wife Agda (Annika Tretow), and the old canard about how "the show must go on" starts to feel increasingly labored as men, horses, and dancing bears all start to suffer from the effects of a life without food or shelter.

Delicately layered, but far easier than most of Bergman's later films (compared even to Smiles of a Summer Night or The Seventh Seal, it's terrifically straightforward), Sawdust and Tinsel is basically a fable about how dreams die and how the grinding needs of life outweigh such niceties as ideals and love (the original Swedish title translates loosely as "The Clown's Evening", but I'd reckon that the English title is far more expressive, reducing the magic of the circus to cheap trappings - sawdust and tinsel are both the stuff of the performance, and the trash lying in the gutter when the performance ends). A perfectly Bergmanesque sentiment, then, and one that lies far removed from how e.g. Fellini might have treated the same matter. Not an idle comparison; Sadust and Tinsel is more than a bit reminiscent of La strada or Variety Lights, Fellini's collaboration with Alberto Lattuada, and of course the Italian filmmaker's career is positively riddled with clowns; but where Fellini would have privileged the humane quality of the story, even the idea that performers are a family who need love just like anybody, Bergman is strictly focused on his characters' degradations - and in this, too, Sawdust and Tinsel looks ahead to his future work.

One of the key moments in the film comes when Albert goes to beg help from Sjuberg (Gunnar Björnstrand), the director of a rag-tag theater troupe. Sjuberg rebuffs him, and in a strangely angry moment declares that actors put themselves to greater danger than circus performers; since the carnies only risk their lives, while actors risk their pride. As a statement of artistic principals, that's a straightforward idea which we could debate for days, but within the film, it has another clear meaning: Albert and his crew must risk their lives because they have no pride left - by the time we meet them, a lifetime of humiliations has all but destroyed the human dignity they ever possessed.

Strange for a filmmaker who professed until the end of his life that theater was his first and truest love to make a film - his first set in the world of performing arts - that would go to such lengths to make it seem that theatrical performers (on stage, under the tent) suffer horrid degradations and lead miserable lives; but then again, he was Ingmar Bergman, a man who never stopped fixating on the amount of suffering humans could withstand, nor on those humans ability or inability to survive that suffering and emerge with their souls intact. Sawdust and Tinsel is neither his most miserable nor his most humane film, but in this as well as everything else, it is a tremendous first step.