I knew Norma Shearer. Norma Shearer was a friend of mine. Ms. Ryan, you're no Norma Shearer.

I find it gratifying, that the remake of The Women opened the same weekend as Righteous Kill, for this provides us with a marvelous snapshot of the contempt with which the great Hollywood marketing beast divides its audience into gender roles; at least I assume that nobody will have much issue with my argument that the films are being sold primarily based on the user's genitalia. The lesson that this weekend teaches us, is that film executives think that men like to watch other men swagger and say "fuck" a lot in putatively sarcastic ways, as women stand on the sidelines and look sexy; while women like to look at other women wearing expensive clothes. But no matter how different men and women might be on the surface, we're all expected to be tremendous idiots who'll gobble up whatever pablum the studios crap out, and be grateful for the pandering. We've also learned this weekend that, as ever, great films and great roles know no gender, and the best films are the ones that trust their audience with the most sophistication; and the fact that Burn After Reading won the weekend box office is extraordinarily comforting to me.

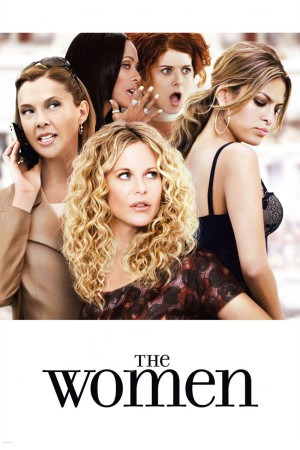

The Women was first filmed in 1939, based upon a hit play by Clare Boothe Luce (a woman) with a screenplay by Anita Loos and Jane Murfin (two women), and directed by George Cukor (a gay man and the greatest director of "women's pictures" in the 1930s), and while its gender politics could never be viewed as anything but the product of a less-enlightened time, it has enough brains and wit that it's still a terrific delight 79 years later. The new film, written and directed by Diane English (a soulless automaton), making her first feature after creating Murphy Brown, is not delightful at all, and while there are many ways in which it falls short of its predecessor the fact that it possesses, arguably, a more retrograde view of gender roles, while neither the greatest nor most obvious sin, is probably the most depressing.

Luce's flash of genius way back when, after all, was that she didn't stop at writing about bitchy women in New York's high society; the big secret of The Women in its original form is that it's more of a commentary on class differences than a story about women and their womanly problems. You could do that, back in the '30s; sexism or not, a quick scan of the "woman's picture" genre reveals that the filmmakers in question assumed that their audience would be smart enough to understand the more thoughtful parts of the story while also enjoying the superficial charms of the film's comedy. No such assumption girds English's film, which insofar as it possesses any class consciousness at all, it's to shrink in horror from the very concept that a mere shopgirl would view herself as the equal to the intelligentsia. If Cukor's film was a satire of the nattering classes whose lives revolved around gossip, cocktail parties and the new fashions, the remake is a full-throated endorsement of the lifestyle which begins and ends with the question: "What is she wearing?" The key difference between the two is revealed during their respective credits: while the 1939 film opens by dissolving each of the star's faces into the wild animal they most represent, the 2008 film introduces us to the characters with a close-up on...their shoes.

The plots aren't identical, but they're close for at least the first half: Mary Haines (Meg Ryan) is the last one to find out that her husband Stephen is screwing around with a perfume girl at Saks, Crystal Allen (Eva Mendes). The first to find out is Mary's best friend, the compulsive gossip Sylvia Fowler (Annette Bening), who pretends that she doesn't really want to tell the other members of their clique, Edie Cohen (Debra Messing) and Alex Fisher (Jada Pinkett Smith). When Mary does find out, it leads to a great deal of soul-searching and identity-finding, aided by her caustic mother Catherine Frazier (Candice Bergen), her housekeeper Maggie (Cloris Leachman), and ever her daughter Molly (India Ennenga). In the end, she learns the Very Special Lesson that you can't be a good friend or wife until you know who you are, and stop hiding your identity to make other people happy. Knowing who you are requires the acquisition of really nice clothing and accessories, incidentally.

That's a bit sweeter and a lot less interesting than the original film, which concluded, essentially, that people will behave like jackals for a little bit of money and prestige, and the difference is largely in how Crystal is approached in the two projects. Luce viewed the perfume girl as the most sympathetic character in the piece, and while the '39 film doesn't quite reach that point, she still emerges as a much more complex antagonist than the shrill harridan of the remake, given only a fraction of the screentime and none of the motivation. She's a harpy, pure and simple, a buffoon who needs to learn her place. It doesn't help matters whatsoever that Mendes is playing a role given in the original to Joan Crawford, one of the most lopsided competitions between two performers in history. Yes, it's a bit easier to believe Mendes as a sexpot who could have any many she wanted - for a time. But Crawford is a force of nature, and if she hooks you, you stay hooked; not only does she make for a more credible threat, she's infinitely more human.

Acting, unfortunately, is one of the new film's weakest suits, gathering as big a group of famous ladies as it can, most of whom aren't actually very good to start with. Ryan, despite a brief burst of greatness at the turn of the '90s (consisting, by my reckoning, of two films: When Harry Met Sally... and Joe Versus the Volcano) has never had much to recommend her other than a tremendous native ability to be bubbly on cue, and the forced facial expressions that make up the bulk of her performance aren't just a pale reflection of Norma Shearer's great take on the same role, it's shallow and uninteresting by any yardstick. Bening, taking on the role that made Rosalind Russell a comic star (and thus led directly to His Girl Friday and the finest comic performance in cinema history), is a great deal better - she's Annette Fucking Bening, after all, and would be a greater actress sleepwalking. Which is apparently what she's doing in this film, playing the "driven professional woman with a heart" card as typically as it could be played. In the smaller roles, filling out the Sex and the City-influenced foursome Messing and Pinkett Smith are nothing but warm bodies, though at least Pinkett Smith has the excuse of playing an essentially unplayable role, as the token lesbian/ non-white, artistically blocked intellectual essayist. The only performers who escape mostly intact are Bette Midler in the role of the cynical divorce veteran changed a great deal from the original, and Leachman, who between the two of them provide the only brassiness in the whole airless project.

The less said about English's directorial style, the better. This looks precisely like the first feature of a television graduate ought to look, with eternal shot-reverse shot conversations and lighting aimed at making sure everything is visible, rather than adding any hint of atmosphere or texture. That's another thing that we don't have anymore that we used to have by the bucketful in the 1930s: comic directors who knew how to make good films.

At the very least, it's a tiny bit better than Righteous Kill; at least, it's too glossy and forgettable to be quite as obnoxious. But if this is what pop culture actually regards as appropriate fare for them, y'know, those "women" who occasionally pop in conversations about niche audiences, it's no wonder that the gender dialogue in this country is so terminally fucked.

4/10

The Women was first filmed in 1939, based upon a hit play by Clare Boothe Luce (a woman) with a screenplay by Anita Loos and Jane Murfin (two women), and directed by George Cukor (a gay man and the greatest director of "women's pictures" in the 1930s), and while its gender politics could never be viewed as anything but the product of a less-enlightened time, it has enough brains and wit that it's still a terrific delight 79 years later. The new film, written and directed by Diane English (a soulless automaton), making her first feature after creating Murphy Brown, is not delightful at all, and while there are many ways in which it falls short of its predecessor the fact that it possesses, arguably, a more retrograde view of gender roles, while neither the greatest nor most obvious sin, is probably the most depressing.

Luce's flash of genius way back when, after all, was that she didn't stop at writing about bitchy women in New York's high society; the big secret of The Women in its original form is that it's more of a commentary on class differences than a story about women and their womanly problems. You could do that, back in the '30s; sexism or not, a quick scan of the "woman's picture" genre reveals that the filmmakers in question assumed that their audience would be smart enough to understand the more thoughtful parts of the story while also enjoying the superficial charms of the film's comedy. No such assumption girds English's film, which insofar as it possesses any class consciousness at all, it's to shrink in horror from the very concept that a mere shopgirl would view herself as the equal to the intelligentsia. If Cukor's film was a satire of the nattering classes whose lives revolved around gossip, cocktail parties and the new fashions, the remake is a full-throated endorsement of the lifestyle which begins and ends with the question: "What is she wearing?" The key difference between the two is revealed during their respective credits: while the 1939 film opens by dissolving each of the star's faces into the wild animal they most represent, the 2008 film introduces us to the characters with a close-up on...their shoes.

The plots aren't identical, but they're close for at least the first half: Mary Haines (Meg Ryan) is the last one to find out that her husband Stephen is screwing around with a perfume girl at Saks, Crystal Allen (Eva Mendes). The first to find out is Mary's best friend, the compulsive gossip Sylvia Fowler (Annette Bening), who pretends that she doesn't really want to tell the other members of their clique, Edie Cohen (Debra Messing) and Alex Fisher (Jada Pinkett Smith). When Mary does find out, it leads to a great deal of soul-searching and identity-finding, aided by her caustic mother Catherine Frazier (Candice Bergen), her housekeeper Maggie (Cloris Leachman), and ever her daughter Molly (India Ennenga). In the end, she learns the Very Special Lesson that you can't be a good friend or wife until you know who you are, and stop hiding your identity to make other people happy. Knowing who you are requires the acquisition of really nice clothing and accessories, incidentally.

That's a bit sweeter and a lot less interesting than the original film, which concluded, essentially, that people will behave like jackals for a little bit of money and prestige, and the difference is largely in how Crystal is approached in the two projects. Luce viewed the perfume girl as the most sympathetic character in the piece, and while the '39 film doesn't quite reach that point, she still emerges as a much more complex antagonist than the shrill harridan of the remake, given only a fraction of the screentime and none of the motivation. She's a harpy, pure and simple, a buffoon who needs to learn her place. It doesn't help matters whatsoever that Mendes is playing a role given in the original to Joan Crawford, one of the most lopsided competitions between two performers in history. Yes, it's a bit easier to believe Mendes as a sexpot who could have any many she wanted - for a time. But Crawford is a force of nature, and if she hooks you, you stay hooked; not only does she make for a more credible threat, she's infinitely more human.

Acting, unfortunately, is one of the new film's weakest suits, gathering as big a group of famous ladies as it can, most of whom aren't actually very good to start with. Ryan, despite a brief burst of greatness at the turn of the '90s (consisting, by my reckoning, of two films: When Harry Met Sally... and Joe Versus the Volcano) has never had much to recommend her other than a tremendous native ability to be bubbly on cue, and the forced facial expressions that make up the bulk of her performance aren't just a pale reflection of Norma Shearer's great take on the same role, it's shallow and uninteresting by any yardstick. Bening, taking on the role that made Rosalind Russell a comic star (and thus led directly to His Girl Friday and the finest comic performance in cinema history), is a great deal better - she's Annette Fucking Bening, after all, and would be a greater actress sleepwalking. Which is apparently what she's doing in this film, playing the "driven professional woman with a heart" card as typically as it could be played. In the smaller roles, filling out the Sex and the City-influenced foursome Messing and Pinkett Smith are nothing but warm bodies, though at least Pinkett Smith has the excuse of playing an essentially unplayable role, as the token lesbian/ non-white, artistically blocked intellectual essayist. The only performers who escape mostly intact are Bette Midler in the role of the cynical divorce veteran changed a great deal from the original, and Leachman, who between the two of them provide the only brassiness in the whole airless project.

The less said about English's directorial style, the better. This looks precisely like the first feature of a television graduate ought to look, with eternal shot-reverse shot conversations and lighting aimed at making sure everything is visible, rather than adding any hint of atmosphere or texture. That's another thing that we don't have anymore that we used to have by the bucketful in the 1930s: comic directors who knew how to make good films.

At the very least, it's a tiny bit better than Righteous Kill; at least, it's too glossy and forgettable to be quite as obnoxious. But if this is what pop culture actually regards as appropriate fare for them, y'know, those "women" who occasionally pop in conversations about niche audiences, it's no wonder that the gender dialogue in this country is so terminally fucked.

4/10

Categories: chick flicks, needless remakes, unfunny comedies