They Shoot Pictures, Don't They? 2008 Edition - #281

Confronted with a film that seems to come out of nowhere, and do things that no other film in my experience has done in quite the same way, my brain struggles mightily to come up with some comfortably familiar framework to fit that film, and here's what I've come up with for Johnny Guitar: it's like a Howard Hawks Western as directed by melodramatist Douglas Sirk. Kind of.

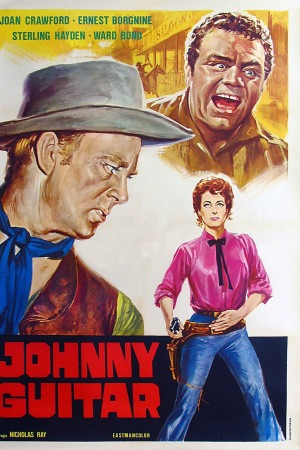

Johnny Guitar is the story of Vienna (Joan Crawford), a woman who builds a gambling hall in Arizona, miles from the nearest town but right by the proposed path of a new railroad; of Emma Small (Mercedes McCambridge), the local moralist whose brother was killed in a robbery blamed on a gang Vienna has some ties to; of the Dancin' Kid (Scott Brady), the gang leader who loves Vienna and just wants to be left alone with his silver mine and his lady; and of John Logan, AKA Johnny Guitar (Sterling Hayden), Vienna's old flame who comes at her invitation to play guitar, despite his hot temper and deadly pistol. And it is quite possibly the weirdest Western ever made by a mainstream studio in the 1950s

It's rare enough, after all, for a Western to feature two well-rounded female characters, and I'm damned if I can come up with another one that has the audacity to set those two characters up as the primary source of plot conflict. This is a story of Vienna and Emma all the way, with everybody else, even the title character, coming along merely to flesh out the edges. Admittedly, they don't resemble actual women any more than the men in the cast resemble actual human males, particularly given the film's eagerness to leap to Freudian explanations for everything that happens. But this isn't really a liability, given the outsized campiness involved, a campiness which might well alienate plenty of hard-core Western fans and modern viewers unaccustomed to the heavily stylised acting that entails, but for my money puts Johnny Guitar high in the running for the most interesting Western of the studio system not directed by John Ford.

This is the film, after all, of which Jean-Luc Godard - a man given to hyperbole - once claimed, to love cinema is to love Johnny Guitar (a restrained comment, in its own twisted way; Martin Scorsese has said something similar about the entire corpus of director Sam Fuller). This was right in the heart of Godard's first love for the films of Nicholas Ray, a director best known today mostly for Rebel Without a Cause, but whom the true cinephile recognises as one of the all-around brashest directors of the post-war era (Ray is also a director whose supporters are given to breathless praise and phrases like "true cinephile"). I don't mean to belittle They Live by Night or On Dangerous Ground or other masterworks if I suggest that Johnny Guitar is my new favorite Ray film; at any rate, it seems like it might be the most Rayvian, with its fixation on isolation vs. civilisation and Johnny's one-line encapsulation of the director's whole career: "I'm a stranger here myself."

It's a film that hops madly from one style to another, and from black comedy to thriller and back, and never once in nearly two hours does it strain in doing so. The opening 40 minutes are a real-time introduction to the characters and the situation all on one set; yet it might also be the most thrillingly cinematic part of the whole movie, with Ray quickly dividing the cast into groups based primarily on how he films them: Vienna and Johnny in still medium shots (they are calm and in control), the Dancin' Kid's gang in handheld (or at least, unfixed) medium and medium-wide shots that typically seem to spill off the edge of the frame (they're a bit loose and anarchic), and Emma and the gang of righteous citizenry in wider shots that always emphasise the collective backing up the individual (she's authoritarian). It's almost a disappointment, in fact, when the film moves out into the open country and starts to look a lot more like every other great Western of the era, as shot by the typically brilliant Harry Stradling.

Judging from a quick spin 'round the internet, it would appear that the modern viewer tends to have a problem with the film's hammiest aspects, primarily its gonzo psychoanalytic drama (Emma is a sexually repressed prude who hates Vienna for being a liberated woman, and Dancin' Kid for being the object of her own repressed lust), and the outrageous acting involved. And certainly, the acting is pretty big in this movie: Hayden appears to have stepped untouched from a film noir, and Crawford is at her very draggiest (one character approvingly claims that she's more of a man than a woman). Maybe it's just my affection for the decade talking, but I tend to see these as positives, not negatives. The 15 years after the end of World War II were a strange time in the history of American gender roles; after supporting industry for five years, women were suddenly required to step back into the shadows and let the boys take over, and this caused no end of anxiety all over the country. Johnny Guitar tries to have it both ways, unbashedly praising female sexuality while punishing Vienna by destroying her dreams of economic power. At any rate, the Freudian tone to the film is just its extremely unsubtle way of forcing those issues right to the top of our minds; and who says subtlety is always so damned important. And about the acting...well, you either like ham or you don't. There's nothing believable about the performances precisely because there isn't supposed to be: this is the story of immovable objects and irresistable forces, not actual people. That's what "melodrama" means.

My critical faculties might not be so sharp here; it's just that I flat-out loved this movie. I loved that every character is a shitheel, and the only reason we like some of the shitheels is that they want to do their own thing in peace; the villains are the ones who want to force their own brand of shit on everybody. I loved that it has that garish soft look of 1950s color films. I love that Nicholas Ray's camera can't make up its mind if it would rather be stately or insane. I love that when Sterling Hayden says that a real man only needs a cup of coffee and a good smoke, it looks like he wants to have sex with both of those things. Sure this is all over-the-top, but it's tremendously entertaining, and brilliantly executed, and dammit, there's even a bit of raw human passion in there if you look a little bit.

Johnny Guitar is the story of Vienna (Joan Crawford), a woman who builds a gambling hall in Arizona, miles from the nearest town but right by the proposed path of a new railroad; of Emma Small (Mercedes McCambridge), the local moralist whose brother was killed in a robbery blamed on a gang Vienna has some ties to; of the Dancin' Kid (Scott Brady), the gang leader who loves Vienna and just wants to be left alone with his silver mine and his lady; and of John Logan, AKA Johnny Guitar (Sterling Hayden), Vienna's old flame who comes at her invitation to play guitar, despite his hot temper and deadly pistol. And it is quite possibly the weirdest Western ever made by a mainstream studio in the 1950s

It's rare enough, after all, for a Western to feature two well-rounded female characters, and I'm damned if I can come up with another one that has the audacity to set those two characters up as the primary source of plot conflict. This is a story of Vienna and Emma all the way, with everybody else, even the title character, coming along merely to flesh out the edges. Admittedly, they don't resemble actual women any more than the men in the cast resemble actual human males, particularly given the film's eagerness to leap to Freudian explanations for everything that happens. But this isn't really a liability, given the outsized campiness involved, a campiness which might well alienate plenty of hard-core Western fans and modern viewers unaccustomed to the heavily stylised acting that entails, but for my money puts Johnny Guitar high in the running for the most interesting Western of the studio system not directed by John Ford.

This is the film, after all, of which Jean-Luc Godard - a man given to hyperbole - once claimed, to love cinema is to love Johnny Guitar (a restrained comment, in its own twisted way; Martin Scorsese has said something similar about the entire corpus of director Sam Fuller). This was right in the heart of Godard's first love for the films of Nicholas Ray, a director best known today mostly for Rebel Without a Cause, but whom the true cinephile recognises as one of the all-around brashest directors of the post-war era (Ray is also a director whose supporters are given to breathless praise and phrases like "true cinephile"). I don't mean to belittle They Live by Night or On Dangerous Ground or other masterworks if I suggest that Johnny Guitar is my new favorite Ray film; at any rate, it seems like it might be the most Rayvian, with its fixation on isolation vs. civilisation and Johnny's one-line encapsulation of the director's whole career: "I'm a stranger here myself."

It's a film that hops madly from one style to another, and from black comedy to thriller and back, and never once in nearly two hours does it strain in doing so. The opening 40 minutes are a real-time introduction to the characters and the situation all on one set; yet it might also be the most thrillingly cinematic part of the whole movie, with Ray quickly dividing the cast into groups based primarily on how he films them: Vienna and Johnny in still medium shots (they are calm and in control), the Dancin' Kid's gang in handheld (or at least, unfixed) medium and medium-wide shots that typically seem to spill off the edge of the frame (they're a bit loose and anarchic), and Emma and the gang of righteous citizenry in wider shots that always emphasise the collective backing up the individual (she's authoritarian). It's almost a disappointment, in fact, when the film moves out into the open country and starts to look a lot more like every other great Western of the era, as shot by the typically brilliant Harry Stradling.

Judging from a quick spin 'round the internet, it would appear that the modern viewer tends to have a problem with the film's hammiest aspects, primarily its gonzo psychoanalytic drama (Emma is a sexually repressed prude who hates Vienna for being a liberated woman, and Dancin' Kid for being the object of her own repressed lust), and the outrageous acting involved. And certainly, the acting is pretty big in this movie: Hayden appears to have stepped untouched from a film noir, and Crawford is at her very draggiest (one character approvingly claims that she's more of a man than a woman). Maybe it's just my affection for the decade talking, but I tend to see these as positives, not negatives. The 15 years after the end of World War II were a strange time in the history of American gender roles; after supporting industry for five years, women were suddenly required to step back into the shadows and let the boys take over, and this caused no end of anxiety all over the country. Johnny Guitar tries to have it both ways, unbashedly praising female sexuality while punishing Vienna by destroying her dreams of economic power. At any rate, the Freudian tone to the film is just its extremely unsubtle way of forcing those issues right to the top of our minds; and who says subtlety is always so damned important. And about the acting...well, you either like ham or you don't. There's nothing believable about the performances precisely because there isn't supposed to be: this is the story of immovable objects and irresistable forces, not actual people. That's what "melodrama" means.

My critical faculties might not be so sharp here; it's just that I flat-out loved this movie. I loved that every character is a shitheel, and the only reason we like some of the shitheels is that they want to do their own thing in peace; the villains are the ones who want to force their own brand of shit on everybody. I loved that it has that garish soft look of 1950s color films. I love that Nicholas Ray's camera can't make up its mind if it would rather be stately or insane. I love that when Sterling Hayden says that a real man only needs a cup of coffee and a good smoke, it looks like he wants to have sex with both of those things. Sure this is all over-the-top, but it's tremendously entertaining, and brilliantly executed, and dammit, there's even a bit of raw human passion in there if you look a little bit.