An old woman's tale

A small elderly woman walks through a train yard on a scorching hot day, looking for her ride. Eventually she comes to an armored military train, loaded with sweaty, dusty soldiers, who are glad to help the woman up into their dingy hold. As the train pulls out, the men discuss how best to afford her some measure of privacy for the long night trip to their base.

Thus begins Aleksandra, the latest film by Russian filmmaker and former avant-gardist Aleksandr Sokurov, best known to this country's arthouse crowds for his bravura 2002 film Russian Ark, a feature-length exploration of Russia's history and love/hate relationship with Europe noted for being filmed in one uninterrupted take. There's little of that film's style in Aleksandra, but they share the same overriding theme: what does it mean to be Russian in a given place and time?

The place and time presented in the director's new film is modern Chechnya, the much-disputed Islamic republic straining for independence from Russia; the setting is a military base manned by the Russian army, and the small town lying outside its walls. The figure with whom we move through this setting is Aleksandra Nikolaevna, played by 81-year-old Galina Vishnevskaya, a beloved and internationally reknowned opera diva. That she is one of Russia's living operatic treasures - and that she was once a friend of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn - have very little to do with her presence in Aleksandra; far more important is her almost comic appearance, a tiny, rounded, wrinkly old lady in simple clothes and a babushka, looking kind of like every grandma who ever existed.

That's why she's traveling to Chechnya, you see; because she's a grandma. It's been seven years since she's seen her adult grandson Denis (Vasily Shevtsov), an officer (probably, but the film never really makes it clear, because it's not really important) stationed in that country. Without any apparent motivation besides the love that grandmas have for their descendants, she makes the long journey mostly to say "hi" and poke around and look at things.

And poking around, and looking, are just what she does. If I tried to synopsise the plot of Aleksandra, I'd probably go a little bit nuts, for there's not any plot that you could tell. Instead, there are scenes of Aleksandra meeting people and talking about this and that, and frequently finding herself out of breath and ready for a sit-down, which she frequently enjoys with the old Chechen woman Malika (Raisa Gichaeva), who runs a general store in the bombed-out remains of her house, just a bit outside the base.

From this reed-thin premise, Sokurov drafts one of the few truly poetic films of the current decade. His vision of Chechnya is mesmerising and unreal, as idiosyncratic as a vision by David Lynch, though in no way comparable (I really can't think of anything to compare it to, in fact; maybe Sokurov's other films, but the only three I've seen - including Mother and Son and Father and Son - are probably more dissimilar than similar). This starts with the film's incredible appearance: processed to look almost like yellow monochrome (the eagle-eyed will pick out the odd red or green every so often, very muted), the screen is positively arid with the mercyless heat and dust of the Chechen summer. It looks nothing like a film set in a modern army base ought to look; if anything, it reminded me of a post-apocalyptic thriller, where the whole planet had been turned to desert.

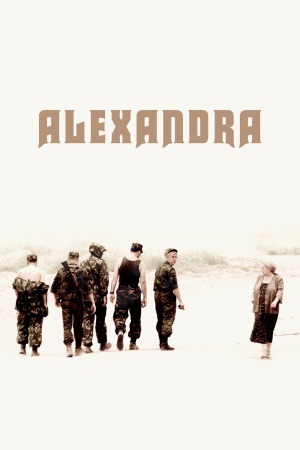

That's saying nothing about the bizarre images of tiny Aleksandra moving blithely around the soldiers and their world, a homey picture of Russian tradition thrust incongruously amongst tanks and bunkers and guns. So inconceivable does this seem that the film can't help but morph into a kind of magical realism: the charming old lady crash-landed in a yellow alien world.

Aleksandra is basically a fairy tale, in the end, so the magical realism suits it (and I should perhaps say "fable", not "fairy tale"). As the fairy, Aleksandra herself is both character and symbol, the former revealed mostly in her subtle and beautiful conversations with Malika, the latter in her interactions with the soldiers. It's clear that they are more than a little delighted by her presence, rather than tolerant or ironically amused, and one might say without stretching that they all fall somewhat in love with her; she represents an unstoppable life force in the midst of death, quintessential Russinaness in a place where Russians are not meant to be, neither wanting to stay nor wanted by the locals.

This last part is the key to Sokurov's political statement within the movie, although a gentler, less-polemic political film has rarely been made. Aleksandra is essentially a film about absurdity: it's obvious though never stated outright that Aleksandra's presence in Chechnya is absurd, and she metaphorically stands in for Russia's equally-absurd presence in that place. The filmmaker is never obliged to lecture us about how very bad this situation is; it's patently obvious to us, the more we realise that nobody in the film is very happy except when Aleksandra is there to remind them of what life can be without war.

Here is what filmmaking looks like at its absolute best: a movie of bold and aggressive originality that expresses itself with the utmost delicacy. Seeing Aleksandra is like permitting Sokurov to arrange your dreams for you: it is highly intellectual and simultaneously, absolutely intuitive, like the best work of Kieslowski or Dreyer. Watching that stumpy little woman dragging her suitcase around is seeing humanity expressed onscreen in its absolute form, undoubtedly artificial but so truthful as to be overwhelming.

10/10

Thus begins Aleksandra, the latest film by Russian filmmaker and former avant-gardist Aleksandr Sokurov, best known to this country's arthouse crowds for his bravura 2002 film Russian Ark, a feature-length exploration of Russia's history and love/hate relationship with Europe noted for being filmed in one uninterrupted take. There's little of that film's style in Aleksandra, but they share the same overriding theme: what does it mean to be Russian in a given place and time?

The place and time presented in the director's new film is modern Chechnya, the much-disputed Islamic republic straining for independence from Russia; the setting is a military base manned by the Russian army, and the small town lying outside its walls. The figure with whom we move through this setting is Aleksandra Nikolaevna, played by 81-year-old Galina Vishnevskaya, a beloved and internationally reknowned opera diva. That she is one of Russia's living operatic treasures - and that she was once a friend of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn - have very little to do with her presence in Aleksandra; far more important is her almost comic appearance, a tiny, rounded, wrinkly old lady in simple clothes and a babushka, looking kind of like every grandma who ever existed.

That's why she's traveling to Chechnya, you see; because she's a grandma. It's been seven years since she's seen her adult grandson Denis (Vasily Shevtsov), an officer (probably, but the film never really makes it clear, because it's not really important) stationed in that country. Without any apparent motivation besides the love that grandmas have for their descendants, she makes the long journey mostly to say "hi" and poke around and look at things.

And poking around, and looking, are just what she does. If I tried to synopsise the plot of Aleksandra, I'd probably go a little bit nuts, for there's not any plot that you could tell. Instead, there are scenes of Aleksandra meeting people and talking about this and that, and frequently finding herself out of breath and ready for a sit-down, which she frequently enjoys with the old Chechen woman Malika (Raisa Gichaeva), who runs a general store in the bombed-out remains of her house, just a bit outside the base.

From this reed-thin premise, Sokurov drafts one of the few truly poetic films of the current decade. His vision of Chechnya is mesmerising and unreal, as idiosyncratic as a vision by David Lynch, though in no way comparable (I really can't think of anything to compare it to, in fact; maybe Sokurov's other films, but the only three I've seen - including Mother and Son and Father and Son - are probably more dissimilar than similar). This starts with the film's incredible appearance: processed to look almost like yellow monochrome (the eagle-eyed will pick out the odd red or green every so often, very muted), the screen is positively arid with the mercyless heat and dust of the Chechen summer. It looks nothing like a film set in a modern army base ought to look; if anything, it reminded me of a post-apocalyptic thriller, where the whole planet had been turned to desert.

That's saying nothing about the bizarre images of tiny Aleksandra moving blithely around the soldiers and their world, a homey picture of Russian tradition thrust incongruously amongst tanks and bunkers and guns. So inconceivable does this seem that the film can't help but morph into a kind of magical realism: the charming old lady crash-landed in a yellow alien world.

Aleksandra is basically a fairy tale, in the end, so the magical realism suits it (and I should perhaps say "fable", not "fairy tale"). As the fairy, Aleksandra herself is both character and symbol, the former revealed mostly in her subtle and beautiful conversations with Malika, the latter in her interactions with the soldiers. It's clear that they are more than a little delighted by her presence, rather than tolerant or ironically amused, and one might say without stretching that they all fall somewhat in love with her; she represents an unstoppable life force in the midst of death, quintessential Russinaness in a place where Russians are not meant to be, neither wanting to stay nor wanted by the locals.

This last part is the key to Sokurov's political statement within the movie, although a gentler, less-polemic political film has rarely been made. Aleksandra is essentially a film about absurdity: it's obvious though never stated outright that Aleksandra's presence in Chechnya is absurd, and she metaphorically stands in for Russia's equally-absurd presence in that place. The filmmaker is never obliged to lecture us about how very bad this situation is; it's patently obvious to us, the more we realise that nobody in the film is very happy except when Aleksandra is there to remind them of what life can be without war.

Here is what filmmaking looks like at its absolute best: a movie of bold and aggressive originality that expresses itself with the utmost delicacy. Seeing Aleksandra is like permitting Sokurov to arrange your dreams for you: it is highly intellectual and simultaneously, absolutely intuitive, like the best work of Kieslowski or Dreyer. Watching that stumpy little woman dragging her suitcase around is seeing humanity expressed onscreen in its absolute form, undoubtedly artificial but so truthful as to be overwhelming.

10/10