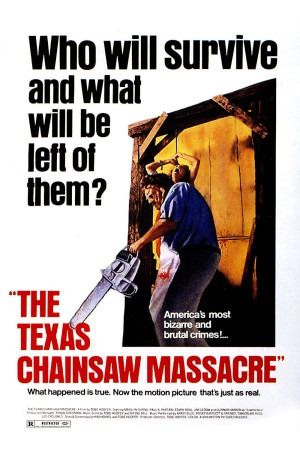

Summer of Blood: One of the most bizarre crimes in the annals of American history

Facts are facts, and it's a fact that everything obvious and a whole lot of things that aren't obvious about The Texas Chainsaw Massacre has been said, and anyone with the guts to try adding to that mountain of criticism better have something original, or at least shockingly bold, to say about the film.

I'm going to settle for shockingly bold: The Texas Chainsaw Massacre is the key American film of the 1970s.

Let's tiptoe through history, shall we? Cinematically, that decade was born in the blood that closed out Bonnie and Clyde, and it was baptised by the senseless violence that ended Easy Rider and peppered the entirety of The Wild Bunch. One of the key films early in the decade was Kubrick's nihilistic anti-comedy A Clockwork Orange; the huge box-office smash The Godfather and its sequel were love letters to the immoral depths of organised crime, and it was knocked from its high-grossing throne by The Exorcist, in which a possessed pubescent girl rapes herself with a crucifix. Later, the film that begot the very idea of the blockbuster was a violent, talky shark movie where a preteen boy dies midway through. In 1974, the popular Oscar nominee Chinatown ended with the most nihilistic sucker punch in any mainstream American film before or since, and in 1976, the dour trio of Best Picture nominees All the President's Men, Network and Taxi Driver lost to Rocky, an upbeat sports picture where the hero loses. The decade's most prominent comedy, Annie Hall, suggests that none of us will ever find lasting love. The decade was driven to a close by films like the mirthless Vietnam epic The Deer Hunter, the mirthless Vietnam epic Apocalypse Now and the just plain mirthless Alien. And then there was the decade's final howl from the depths of a tortured soul, the unspeakably draining Raging Bull. Scattered in there were John Cassavetes's explorations into the limits of human suffering, Robert Altman's increasingly bitter genre exercises, and more films about good people losing everything to the forces of progress, capitalism, war and sex than it seems worth listing. If not for Star Wars, you might suppose that the whole population of America was clinically depressed for 12 years.

There's a line of thought that says that successful horror, whether in movie or book or any other form, is supposed to represent the extreme of human endurance, forcing us to look at the worst acts we can imagine so that we are torn apart by the experience and cleansed by the recognition that life is rarely that evil. Horror is the way that we confront our collective id. And horror can only be these things, it can only scare and disturb us - and if it doesn't do those things, what is its value as horror? - if it is harder to withstand than what is "normal" at that moment in time.

(This, I think, explains the brief flare of torture movies that seems to have burned out; with the post-Tarantino crush of silly, funny violence, it takes some seriously depraved shit to move an audience into that place of exquisite anguish).

When the mainstream is marked by things like A Clockwork Orange and Chinatown, that doesn't leave a lot of space for horror to work in. Enter Tobe Hooper, an indie filmmaker with only one movie, the oh-so-minor and long-forgotten Eggshells, under his belt; this unassuming Texan dug into the darkest places that he could find in the darkest decade in American cinema history to produce the single most brutal movie ever made in this country at that time, the film that is the psychotic edge to an already psychotic time. The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, along with Wes Craven's flawed The Last House on the Left is the primal scream of the Nixon years, the film that proved that a generation led to believe over an increasingly dark thirty years that everything good and decent in life was dead or dying, could still come face to face with an abyss that promised, oh no, things can be much more vicious than you've ever thought.

Moreover, Hooper essentially invented the North American slasher movie, along with Bob Clark's Canadian Black Christmas, released just one week later. Without a doubt, the modern viewer armed with the knowledge of Friday the 13th and its endless clones, wouldn't see very much in Hooper's film that looks very "slashery." Still, compared to everything else being made in the US at the time, it's hard not to see how TCM represents the first influx of the tropes that had been making the rounds in Italy for a good decade at that time: a cast of ill-defined victims (college students in TCM, making it a prime example of one of the quintessential slasher characteristics, a young cast), pursued by a rather bloody killer whose motives aren't nearly so important as his modus operandi, and who is better avoided than confronted. And really, compared to all the movies that were to come, TCM has the right ingredients - meet the Expendable Meat, watch everyone but the Final Girl get stalked and killed, and then witness as said Girl outsmarts, or at least outruns, the psycho killer - they're just not in the proportions we'd expect them to be. Plus, compared to virtually every 1980s slasher, it's remarkable how very little blood is on tap in TCM, and since a tale hangs thereon, I'm not going to go any further down that path right now.

Reduced to the basic gestures of its plot, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre is made up almost entirely of sucker punches:

-In August, 1973, the radio announces that someone is robbing graves in Muerto County, Texas, and leaving some of the bodies behind in macabre poses.

-Sally Hardesty (Marilyn Burns), traveling with four of her friends, stop on the way to check on her grandfather's grave.

-The five kids pick up a seriously crazy hitchhiker, who cuts his hand and leaves a strange mark on the side of their van.

-They go to a slightly shady gas station to fill up and get directions to the old Hardesty place.

-The Hardesty place is dark, and there are strange mounds of bone and feather all around.

-The Hardesty place's closest neighbor houses a man in a butcher's apron and a leather mask apparently made of stitched-together human faces, who kills Sally's friends.

-Then he chases Sally to the gas station, wielding a chainsaw.

-Where she learns that the owner (Jim Siedow) is the killer's dad.

-They take her inside their incredibly disturbing home, where they sit her down to family dinner before they kill her.

-She escapes, and a couple truckers show up just as the man in the leather mask is about to kill her with his chainsaw.

Ten story beats in an 84 minute movie, and eight of them are either meant to set us on edge or push us right over. There's an old cliché that gets phrased in different ways, but the nugget is, to hit the ground running and never let up, and Tobe Hopper takes that idea as close to his heart as any horror filmmaker ever has. After a wordy, but nevertheless creepy opening narration (spoken, in his first-ever acting gig, by a young John Larroquette) informing us that Sally Hardesty, her wheelchair-bound brother Franklin (Paul A. Partain), and their friends suffered an extremely shitty day once upon a time, the film cuts to black and the sound of someone breathing heavily; after a few seconds of increasingly unnerving dark, a camera flashbulb reveals ohmigod what was that?! This happens a few times, and finally it's morning and we see what that was: two decomposing corpses propped up obscenely in a Texas graveyard. For the budget the film must have had, the corpses are disturbingly well executed (as it were), and combined with the flashbulbs it's upsetting enough to make a very clear argument, some sixty seconds into the movie: We Are Here To Fuck You Up.

And surely, that is just what the film does, using just about every trick a movie can. Not immediately; for after that magnificently awful opening, the film is content to idle in "creepy and odd things are happening" mode for just over a half-hour. In that time, we will come to find that the five victims are just about the blandest set of people to ever populate a Dead Teenager movie; where a Friday the 13th picture is almost proud to parade its line of stereotypes and to give its Final Girl a single actual characteristic, the only thing that differentiates any of the characters in TCM from each other is that Franklin gets agitated easily, and we know from the narration that Sally is apparently the protagonist. This is perhaps the one indefensible element of an otherwise sterling movie, that it has characters not even paper-thin; they are invisible against the rugged density of paper.

But there are compensations. It doesn't take interesting characters for the surreal encounter with the psychotic hitchhiker (Edwin Neal), whose role in the film is foreshadowed in some unexpectedly subtle ways - indeed, the film is full of unexpectedly subtle moments, where a single line that you're certain to miss the first couple of times through the movie turns out to mean volumes - and whose flare-up of craziness is hammy but presented in the right matter-of-fact way that even though nothing about the scene is credible, it's unbearably tense.

Generally speaking, Hooper's work in this film (though not very often elsewhere in his benighted career) is well-tuned to turning surreal horror into very grounded, plausible terror, and this is a significant element of what makes TCM so damned effective. Much of it has to do with the non-intuitive editing throughout the film: during a conversation early on about the work down in a slaughterhouse (slaughterhouses aren't just thematically important in the film, they're an important plot point), a cow, apparently sick, maybe dead, is flashed up for just a second. Much later, as Sally passes out from terror, Hooper cuts to the outside of the crazy people's house, and crash-zooms back; when she comes to, we fade in, not on what she sees, but on the full moon. This perfectly sums up what happens to Sally (fainting, reviving), but I cannot explain why jumping suddenly to exterior establishing shots is so important. It just is, and that's true of many, many moments in the film, where something is done that makes no sense according to the "rules," but fits exactly right.

Meanwhile, there is also the exemplary, iconic cinematography by Daniel Pearl, in his professional debut. Before moving on to a career packed full of an almost uncountable number of music videos (several rather significant, at that) and far more lousy horror pictures than his talent would seem to demand (and Zapped!) Pearl created what might be the most famously ugly motion picture ever shot. Produced on 16mm film, TCM is as grainy as any major film ever has been, the color saturation is all over the map, and the black levels are charitably charcoal greys. It is surely one of the five best-shot horror films ever produced. That incredibly ugliness, looking not even a full step better than a snuff film, might be the key reason, outside of the production design, why the film is so uncommonly powerful now. In a lifetime full of moviewatching, I have never seen another work that looks so atrociously filthy as TCM, a filth that seeps into your body as you watch. I've seen films that are more disturbing and much scummier, but nothing has ever made me want to shower as much as this does. Those wretched, gritty visuals are entirely unsafe, and while the film's mise en scène would never trick you into thinking it's a documentary, the lowest-fi aesthetic drives it deep into your soul in ways that a polished film could never imagine.

At any rate, for quite a while the film purrs on, ugly and creepy and upsetting, and then two young folks, Kirk (William Vail) and Pam (Teri McMinn), are exploring the spooky old house next door when that man with the leather face (Gunnar Hansen) comes out of a hallway and smashes Kirk on the head with a sledgehammer. Pam looks for Kirk, and stumbles into what I expect was probably the most unpleasant film set in film history: human bones strewn all over, used as decoration and furniture (e.g. a couch made entirely of leg bones), and a chicken in a tiny cage hanging from the ceiling. Even knowing that it's coming, words don't express how monstrously powerful this sight is the first time it appears. Anyway, Pam gets caught by Leatherface pretty quickly, and she's hung on a meat hook to bleed to death offscreen.

In a nutshell, the four kids who die, die fast. The first death in the whole movie is separated from the last death by 17 minutes. That's it. In almost the films structured as this one - a group of people whittled down one at a time until the last hero wins (they're not all slashers, or even all horror) - that I have ever seen, those deaths are stretched out. TCM blows through four murders so quickly that you'd almost think they're an afterthought, on the way to what I think might be the longest, proportionally, Final Girl sequence that I can name. And a tremendously off-kilter one: for almost thirty straight minutes, Sally does nothing but scream: she screams as she runs, she screams as she is strapped to a chair, she screams as the cannibal family's ancient patriarch (John Dugan) sucks blood from her finger. I don't have the words to do justice to the cumulative effect of all the things that happen in those thirty minutes: I can only state plainly that it is draining, as much as any fictional film has ever drained me.

A lot of that is just because of how much the film seems like a nightmare in this sequence, thanks to Hooper's ever more garish camera work and to the depraved set design. The filmmakers are very forthright in the debt their movie owes to the real-life Ed Gein, a Wisconsin man who believed he was transgendered, who murdered and ate women as he tried to figure out how they worked; he salvaged parts of their bodies to decorate his home and make tools from, and this is chiefly what Hooper and company latched on to (Gein is a well-represented figure in the cinema: Robert Bloch took him as the inspiration for Psycho, and it's pretty easy to see his relationship to The Silence of the Lambs). The real-life basis for these terrible images, plus the still-wicked cinematography, plus the fact that Marilyn Burns really did suffer injuries during the film of this sequence, add up to an uncanny, almost unbearable depiction of unmotivated, inexplicable, incomprehensible human suffering.

When the film ends, it ends fast - Wes Craven's Hooper-flavored The Hills Have Eyes ends at the literal instant that the main conflict is over, but TCM ends even sooner, with Leatherface howling in his guttural pig squeal as Sally rides away, not even hundreds of yards down the road. The opening narration indicates that her testimony put an end to the family's depravities, but that's hardly part of the movie. It is as jarring as any ending ever has been, and if you'll forgive me a cliché, it's like the jolt when a really fast, rickety roller coaster pulls in and stops. Although fun movies usually hog the roller coaster comparisons, TCM actually earns it: there's nothing but forward momentum, it's terrifying as hell, and you can't always see what's going on. Because of its brevity and its suddenness, at all points in its plot, it has always struck me that the film is not trying to tell us a story or even scare us in any traditional way; it is assaulting us. It exists only because of the brutal parts of the movie, the parts that most horror pictures bookend with actual, y'know, movie. When those parts has run out of ways to affect us, the movie ends.

This focus on brutality has led many a person to suppose that TCM is excessively violent, including one person who complained about the blood to me personally; yet it is hardly violent at all. Many things are implied, and the meat hook scene doesn't leave a lot the imagination, but the blood and gore are mostly amazing for their absence: the hitchhiker cuts his hand with a pocketknife, some blood is on the wall of Leatherface's abattoir when we first see it, Sally gets cuts running through scrub, and Leatherface gouges his leg with the chainsaw. That is, as far as I can think, all the blood in the whole movie. What it has instead of violence is an extraordinary nastiness of tone, a mindset that mentally tortures the heroine for thirty minutes, that gives the wheelchair kid the most vicious, longest death in the film - the only one done with a chainsaw, so much for your "massacre."

So, "the key American film of the 1970s," I called it, but that was mostly to get your attention. Let's just stick with "a key American film of the 1970s." Which is undeniably true, for only the '70s could have produced a film with this urgent sense of the dark side of the world. It might be the harshest film I can name from that period. Even the unspeakably nasty I Spit on Your Grave ends with the villains getting theirs; TCM is a moral black hole, where unaccountable evil simply exists, above our ability to fight or comprehend it. Call that a response to Watergate or to Vietnam, an angry slam against the failures of the '60s counterculture, or just a smart young director summing up the basest instincts of his species. It's a masterpiece, pure and simple, a vision of nihilism that makes even the grimmest of the more mainstream '70s classics as sweet as an April tulip in comparison.

Body Count: 4, but it's the part that aren't dead bodies that matter.

Reviews in this series

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (Hooper, 1974)

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 (Hooper, 1986)

Leatherface: The Texas Chainsaw Massacre III (Burr, 1990)

Texas Chainsaw Massacre: The Next Generation (Henkel, 1994)

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (Nispel, 2003)

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre: The Beginning (Liebesman, 2006)

Texas Chainsaw 3D (Luessenhop, 2013)

Leatherface (Maury & Bustillo, 2017)

Texas Chainsaw Massacre (Garcia, 2022)

I'm going to settle for shockingly bold: The Texas Chainsaw Massacre is the key American film of the 1970s.

Let's tiptoe through history, shall we? Cinematically, that decade was born in the blood that closed out Bonnie and Clyde, and it was baptised by the senseless violence that ended Easy Rider and peppered the entirety of The Wild Bunch. One of the key films early in the decade was Kubrick's nihilistic anti-comedy A Clockwork Orange; the huge box-office smash The Godfather and its sequel were love letters to the immoral depths of organised crime, and it was knocked from its high-grossing throne by The Exorcist, in which a possessed pubescent girl rapes herself with a crucifix. Later, the film that begot the very idea of the blockbuster was a violent, talky shark movie where a preteen boy dies midway through. In 1974, the popular Oscar nominee Chinatown ended with the most nihilistic sucker punch in any mainstream American film before or since, and in 1976, the dour trio of Best Picture nominees All the President's Men, Network and Taxi Driver lost to Rocky, an upbeat sports picture where the hero loses. The decade's most prominent comedy, Annie Hall, suggests that none of us will ever find lasting love. The decade was driven to a close by films like the mirthless Vietnam epic The Deer Hunter, the mirthless Vietnam epic Apocalypse Now and the just plain mirthless Alien. And then there was the decade's final howl from the depths of a tortured soul, the unspeakably draining Raging Bull. Scattered in there were John Cassavetes's explorations into the limits of human suffering, Robert Altman's increasingly bitter genre exercises, and more films about good people losing everything to the forces of progress, capitalism, war and sex than it seems worth listing. If not for Star Wars, you might suppose that the whole population of America was clinically depressed for 12 years.

There's a line of thought that says that successful horror, whether in movie or book or any other form, is supposed to represent the extreme of human endurance, forcing us to look at the worst acts we can imagine so that we are torn apart by the experience and cleansed by the recognition that life is rarely that evil. Horror is the way that we confront our collective id. And horror can only be these things, it can only scare and disturb us - and if it doesn't do those things, what is its value as horror? - if it is harder to withstand than what is "normal" at that moment in time.

(This, I think, explains the brief flare of torture movies that seems to have burned out; with the post-Tarantino crush of silly, funny violence, it takes some seriously depraved shit to move an audience into that place of exquisite anguish).

When the mainstream is marked by things like A Clockwork Orange and Chinatown, that doesn't leave a lot of space for horror to work in. Enter Tobe Hooper, an indie filmmaker with only one movie, the oh-so-minor and long-forgotten Eggshells, under his belt; this unassuming Texan dug into the darkest places that he could find in the darkest decade in American cinema history to produce the single most brutal movie ever made in this country at that time, the film that is the psychotic edge to an already psychotic time. The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, along with Wes Craven's flawed The Last House on the Left is the primal scream of the Nixon years, the film that proved that a generation led to believe over an increasingly dark thirty years that everything good and decent in life was dead or dying, could still come face to face with an abyss that promised, oh no, things can be much more vicious than you've ever thought.

Moreover, Hooper essentially invented the North American slasher movie, along with Bob Clark's Canadian Black Christmas, released just one week later. Without a doubt, the modern viewer armed with the knowledge of Friday the 13th and its endless clones, wouldn't see very much in Hooper's film that looks very "slashery." Still, compared to everything else being made in the US at the time, it's hard not to see how TCM represents the first influx of the tropes that had been making the rounds in Italy for a good decade at that time: a cast of ill-defined victims (college students in TCM, making it a prime example of one of the quintessential slasher characteristics, a young cast), pursued by a rather bloody killer whose motives aren't nearly so important as his modus operandi, and who is better avoided than confronted. And really, compared to all the movies that were to come, TCM has the right ingredients - meet the Expendable Meat, watch everyone but the Final Girl get stalked and killed, and then witness as said Girl outsmarts, or at least outruns, the psycho killer - they're just not in the proportions we'd expect them to be. Plus, compared to virtually every 1980s slasher, it's remarkable how very little blood is on tap in TCM, and since a tale hangs thereon, I'm not going to go any further down that path right now.

Reduced to the basic gestures of its plot, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre is made up almost entirely of sucker punches:

-In August, 1973, the radio announces that someone is robbing graves in Muerto County, Texas, and leaving some of the bodies behind in macabre poses.

-Sally Hardesty (Marilyn Burns), traveling with four of her friends, stop on the way to check on her grandfather's grave.

-The five kids pick up a seriously crazy hitchhiker, who cuts his hand and leaves a strange mark on the side of their van.

-They go to a slightly shady gas station to fill up and get directions to the old Hardesty place.

-The Hardesty place is dark, and there are strange mounds of bone and feather all around.

-The Hardesty place's closest neighbor houses a man in a butcher's apron and a leather mask apparently made of stitched-together human faces, who kills Sally's friends.

-Then he chases Sally to the gas station, wielding a chainsaw.

-Where she learns that the owner (Jim Siedow) is the killer's dad.

-They take her inside their incredibly disturbing home, where they sit her down to family dinner before they kill her.

-She escapes, and a couple truckers show up just as the man in the leather mask is about to kill her with his chainsaw.

Ten story beats in an 84 minute movie, and eight of them are either meant to set us on edge or push us right over. There's an old cliché that gets phrased in different ways, but the nugget is, to hit the ground running and never let up, and Tobe Hopper takes that idea as close to his heart as any horror filmmaker ever has. After a wordy, but nevertheless creepy opening narration (spoken, in his first-ever acting gig, by a young John Larroquette) informing us that Sally Hardesty, her wheelchair-bound brother Franklin (Paul A. Partain), and their friends suffered an extremely shitty day once upon a time, the film cuts to black and the sound of someone breathing heavily; after a few seconds of increasingly unnerving dark, a camera flashbulb reveals ohmigod what was that?! This happens a few times, and finally it's morning and we see what that was: two decomposing corpses propped up obscenely in a Texas graveyard. For the budget the film must have had, the corpses are disturbingly well executed (as it were), and combined with the flashbulbs it's upsetting enough to make a very clear argument, some sixty seconds into the movie: We Are Here To Fuck You Up.

And surely, that is just what the film does, using just about every trick a movie can. Not immediately; for after that magnificently awful opening, the film is content to idle in "creepy and odd things are happening" mode for just over a half-hour. In that time, we will come to find that the five victims are just about the blandest set of people to ever populate a Dead Teenager movie; where a Friday the 13th picture is almost proud to parade its line of stereotypes and to give its Final Girl a single actual characteristic, the only thing that differentiates any of the characters in TCM from each other is that Franklin gets agitated easily, and we know from the narration that Sally is apparently the protagonist. This is perhaps the one indefensible element of an otherwise sterling movie, that it has characters not even paper-thin; they are invisible against the rugged density of paper.

But there are compensations. It doesn't take interesting characters for the surreal encounter with the psychotic hitchhiker (Edwin Neal), whose role in the film is foreshadowed in some unexpectedly subtle ways - indeed, the film is full of unexpectedly subtle moments, where a single line that you're certain to miss the first couple of times through the movie turns out to mean volumes - and whose flare-up of craziness is hammy but presented in the right matter-of-fact way that even though nothing about the scene is credible, it's unbearably tense.

Generally speaking, Hooper's work in this film (though not very often elsewhere in his benighted career) is well-tuned to turning surreal horror into very grounded, plausible terror, and this is a significant element of what makes TCM so damned effective. Much of it has to do with the non-intuitive editing throughout the film: during a conversation early on about the work down in a slaughterhouse (slaughterhouses aren't just thematically important in the film, they're an important plot point), a cow, apparently sick, maybe dead, is flashed up for just a second. Much later, as Sally passes out from terror, Hooper cuts to the outside of the crazy people's house, and crash-zooms back; when she comes to, we fade in, not on what she sees, but on the full moon. This perfectly sums up what happens to Sally (fainting, reviving), but I cannot explain why jumping suddenly to exterior establishing shots is so important. It just is, and that's true of many, many moments in the film, where something is done that makes no sense according to the "rules," but fits exactly right.

Meanwhile, there is also the exemplary, iconic cinematography by Daniel Pearl, in his professional debut. Before moving on to a career packed full of an almost uncountable number of music videos (several rather significant, at that) and far more lousy horror pictures than his talent would seem to demand (and Zapped!) Pearl created what might be the most famously ugly motion picture ever shot. Produced on 16mm film, TCM is as grainy as any major film ever has been, the color saturation is all over the map, and the black levels are charitably charcoal greys. It is surely one of the five best-shot horror films ever produced. That incredibly ugliness, looking not even a full step better than a snuff film, might be the key reason, outside of the production design, why the film is so uncommonly powerful now. In a lifetime full of moviewatching, I have never seen another work that looks so atrociously filthy as TCM, a filth that seeps into your body as you watch. I've seen films that are more disturbing and much scummier, but nothing has ever made me want to shower as much as this does. Those wretched, gritty visuals are entirely unsafe, and while the film's mise en scène would never trick you into thinking it's a documentary, the lowest-fi aesthetic drives it deep into your soul in ways that a polished film could never imagine.

At any rate, for quite a while the film purrs on, ugly and creepy and upsetting, and then two young folks, Kirk (William Vail) and Pam (Teri McMinn), are exploring the spooky old house next door when that man with the leather face (Gunnar Hansen) comes out of a hallway and smashes Kirk on the head with a sledgehammer. Pam looks for Kirk, and stumbles into what I expect was probably the most unpleasant film set in film history: human bones strewn all over, used as decoration and furniture (e.g. a couch made entirely of leg bones), and a chicken in a tiny cage hanging from the ceiling. Even knowing that it's coming, words don't express how monstrously powerful this sight is the first time it appears. Anyway, Pam gets caught by Leatherface pretty quickly, and she's hung on a meat hook to bleed to death offscreen.

In a nutshell, the four kids who die, die fast. The first death in the whole movie is separated from the last death by 17 minutes. That's it. In almost the films structured as this one - a group of people whittled down one at a time until the last hero wins (they're not all slashers, or even all horror) - that I have ever seen, those deaths are stretched out. TCM blows through four murders so quickly that you'd almost think they're an afterthought, on the way to what I think might be the longest, proportionally, Final Girl sequence that I can name. And a tremendously off-kilter one: for almost thirty straight minutes, Sally does nothing but scream: she screams as she runs, she screams as she is strapped to a chair, she screams as the cannibal family's ancient patriarch (John Dugan) sucks blood from her finger. I don't have the words to do justice to the cumulative effect of all the things that happen in those thirty minutes: I can only state plainly that it is draining, as much as any fictional film has ever drained me.

A lot of that is just because of how much the film seems like a nightmare in this sequence, thanks to Hooper's ever more garish camera work and to the depraved set design. The filmmakers are very forthright in the debt their movie owes to the real-life Ed Gein, a Wisconsin man who believed he was transgendered, who murdered and ate women as he tried to figure out how they worked; he salvaged parts of their bodies to decorate his home and make tools from, and this is chiefly what Hooper and company latched on to (Gein is a well-represented figure in the cinema: Robert Bloch took him as the inspiration for Psycho, and it's pretty easy to see his relationship to The Silence of the Lambs). The real-life basis for these terrible images, plus the still-wicked cinematography, plus the fact that Marilyn Burns really did suffer injuries during the film of this sequence, add up to an uncanny, almost unbearable depiction of unmotivated, inexplicable, incomprehensible human suffering.

When the film ends, it ends fast - Wes Craven's Hooper-flavored The Hills Have Eyes ends at the literal instant that the main conflict is over, but TCM ends even sooner, with Leatherface howling in his guttural pig squeal as Sally rides away, not even hundreds of yards down the road. The opening narration indicates that her testimony put an end to the family's depravities, but that's hardly part of the movie. It is as jarring as any ending ever has been, and if you'll forgive me a cliché, it's like the jolt when a really fast, rickety roller coaster pulls in and stops. Although fun movies usually hog the roller coaster comparisons, TCM actually earns it: there's nothing but forward momentum, it's terrifying as hell, and you can't always see what's going on. Because of its brevity and its suddenness, at all points in its plot, it has always struck me that the film is not trying to tell us a story or even scare us in any traditional way; it is assaulting us. It exists only because of the brutal parts of the movie, the parts that most horror pictures bookend with actual, y'know, movie. When those parts has run out of ways to affect us, the movie ends.

This focus on brutality has led many a person to suppose that TCM is excessively violent, including one person who complained about the blood to me personally; yet it is hardly violent at all. Many things are implied, and the meat hook scene doesn't leave a lot the imagination, but the blood and gore are mostly amazing for their absence: the hitchhiker cuts his hand with a pocketknife, some blood is on the wall of Leatherface's abattoir when we first see it, Sally gets cuts running through scrub, and Leatherface gouges his leg with the chainsaw. That is, as far as I can think, all the blood in the whole movie. What it has instead of violence is an extraordinary nastiness of tone, a mindset that mentally tortures the heroine for thirty minutes, that gives the wheelchair kid the most vicious, longest death in the film - the only one done with a chainsaw, so much for your "massacre."

So, "the key American film of the 1970s," I called it, but that was mostly to get your attention. Let's just stick with "a key American film of the 1970s." Which is undeniably true, for only the '70s could have produced a film with this urgent sense of the dark side of the world. It might be the harshest film I can name from that period. Even the unspeakably nasty I Spit on Your Grave ends with the villains getting theirs; TCM is a moral black hole, where unaccountable evil simply exists, above our ability to fight or comprehend it. Call that a response to Watergate or to Vietnam, an angry slam against the failures of the '60s counterculture, or just a smart young director summing up the basest instincts of his species. It's a masterpiece, pure and simple, a vision of nihilism that makes even the grimmest of the more mainstream '70s classics as sweet as an April tulip in comparison.

Body Count: 4, but it's the part that aren't dead bodies that matter.

Reviews in this series

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (Hooper, 1974)

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 (Hooper, 1986)

Leatherface: The Texas Chainsaw Massacre III (Burr, 1990)

Texas Chainsaw Massacre: The Next Generation (Henkel, 1994)

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (Nispel, 2003)

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre: The Beginning (Liebesman, 2006)

Texas Chainsaw 3D (Luessenhop, 2013)

Leatherface (Maury & Bustillo, 2017)

Texas Chainsaw Massacre (Garcia, 2022)