They Shoot Pictures, Don't They? 2008 Edition - #767

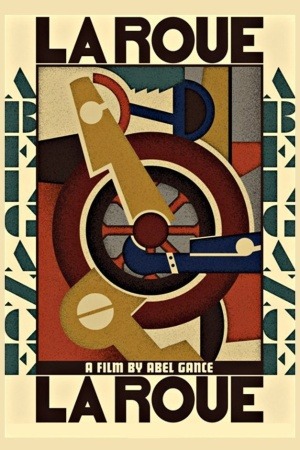

One of the chief pleasures of blogging is that you get to set your own rules. Which means, for example, that if I want to take my weekly classic movie review to shill for a new DVD release, then I can damn well do so. Specifically, I'd like to take a moment to talk about a hugely significant new release, perhaps the most important of the year and certainly the most important silent film: thanks to the folks at the very tiny boutique label Flicker Alley, the world now has the most complete version of Abel Gance's monumental 1922 epic La roue (The Wheel) that has been seen since that film was butchered for its initial British release. "Butchered?" you ask. "Butchered," I repeat: I can think of no other word to describe the reduction of a 32-reel, 7.5 hour epic to an eight-reel, two hour melodrama like everything else coming out at the same time. Admittedly, there was a step in between where the director himself cut it down to 12 reels for more convenient, single-day screenings, but that's small comfort for the the fact that La roue has not been seen in its original version since 1923, and almost certainly never will be again.

The new DVD runs at just a bit less than 4.5 hours, and according to the extensive booklet, it was edited together from five sources: a 35mm print of the 12-reel version, a 35mm Russian print of the eight-reel version, two incomplete 35mm prints from France and a small number of critical scenes from a 9.5mm French home edition. Those looking for a pristine image will be well-advised to look elsewhere; those numerous copies don't all have the same level of quality, and sometimes it's really hard to ignore that. The triumph of this DVD is that it exists at all; not every aspect of its presentation is flawless, chiefly relating to intertitles (the original French titles were often superimposed directly over the picture; a significant advance in 1922). I assume this is an unavoidable by-product of working with French and Russian prints, and at any rate a copy of La roue that is corrupt for a small percentage of its running time is much, much better than no copy of La roue at all.

To reduce the film to its barest elements of story, a melodrama like your grandma used to make, La roue is about Sisif (Séverin-Mars, who died before the picture's release), the finest train engineer in France, who we first meet as he helps to rescue the survivors of an apocalyptic train crash. One of those victims is a little English girl identified only as "Norma," whom Sisif adopts as the little sister to his motherless son Elie. 15 years later, Sisif is still the king of the engineers, Elie (Gabriel de Gravone) is a violin maker searching for an important historical varnish formula, and Norma (Ivy Close) is the beautiful "Rose of the Rails," a darling child who delights everyone that meets her. By this point, Sisif has fallen in love with her, Elie (not knowing that they are not related) is trying to ignore the fact that he is in love with her, and Norma, dimly aware that her presence is causing her father much torment, agrees to marry the wealthy stranger Jacques de Hersan (Pierre Magnier). Sisif is increasingly agitated by this, and when an accident robs him of much of his eyesight, his superiors jump on the excuse to banish him to a rickety train high in the Alps.

That's not a story that can support a 4.5 hour presentation, let alone 7.5 hours, but that's absolutely not the reason Gance made the film. High on the success of the WWI drama J'accuse!, he explicitly conceived of its mammoth follow-up to be an exploration of the art of cinema in all its totality, one of those things that you got to do back in the silent era when the art of cinema was younger than many of its practitioners. Like Griffith's Birth of a Nation seven years prior or Murnau's Sunrise five years later, La roue is nothing less than a snapshot of everything that could be achieved in the form at the time of its creation, and the progenitor of many of the techniques that are still used eight decades on. It's perfectly fair to call it one of the ten most influential and important films ever created, and this is why its new release is so welcome; as the DVD cover crows, no less a figure than Jean Cocteau once claimed "There is the cinema before and after La roue as there is painting before and after Picasso."

The challenge to the modern viewer is that, much as is the case with Birth of a Nation, the film was so successful in its attempts to create a new language that we don't really respect it the way we should, because that's the language we've grown up with. It's easy to say of the Griffith film that it's just a racist adventure movie, not thinking that in 1915, the idea of cutting between two concurrent plotlines was radicalism like most of us cannot imagine; so too in La roue do the editing and cinematography seem needlessly familiar. That's because there has been no reason to improve upon the perfection that La roue created more or less out of whole cloth.

In the DVD liner notes, the claim is made that La roue invented the cross-dissolve; I am not certain that it was the first film released with that technique, but its long production time might well mean that Gance and his cameramen (Dissolves had to be done in-camera back then! The mind reels) came up with the idea before anybody else. Think about that for a second: the dissolve from one scene to another is such a familiar trick that some of us find it to be cheap and tasteless - maybe that's just me - but in 1922, it was brand new. Admittedly, some of the film's most impressive technical leaps are even less interesting to the modern viewer: the use of shocking, bold colors for the tinted scenes is unlike anything I've ever seen, and I cannot think of another movie with such a mature and elaborate system of iris shots (the "pinhole camera" frame) in any other film, but these are both techniques that were essentially dead after the coming of sound. I might also point out that, filming in the studio but also in Nice and at the peak of Mount Blanc, this is one of the earliest and probably the most ambitious of all location shoots in film history, beating John Ford's mythic The Iron Horse to the punch by two years.

These mere historic notes are of course just a part of the film's aesthetic success: it is by any possible yardstick a brilliant-constructed film. "The wheel" it is called, with many great writers quoted where they referred to life's shifting fortunes and failures as a wheel, and rarely has a film's title been used to such effect in the film's visual scheme. Circles dominate La roue, from the wheels of trains in the Nice trainyard to the dance-in-the-round on the plateau of Mount Blanc that closes out the film. Even the iris shots that are used so bravely in the film are an extension of this idea: what is an iris but a circle closing in on the protagonist, cutting him off from the world around? Then there is the matter of the editing, a process which took Gance more than a year to complete, and such editing it is! Tied often to the rhythm of the train's movement, frequently breaking down into a series of shots that last only a frame or two, for several seconds at a time, La roue has the breathless pace of a music video 60 years ahead of time.

It's flaws, however, are not minor, though they are entirely limited to the film's success as a story. I don't mean the length; no good movie is ever too long, and at 4.5 hours, we're just barely getting to know Sisif well by the time we have to leave his company. Rather, the acting is a bit overripe even by the giant standards of the '20s - Séverin-Mars is at his best early and late in the film, when his chest-pounding angst over his lust towards Norma is the least pronounced, but de Gravone, besides being ten years too old for his part, is limp and unpleasant throughout. In the small role of the comic sidekick Machefer, Georges Térof turns the goggle-eyed shock so common in French silent comedy into something actually funny. But the absolute standout is Close, the only significant actor who never feels a bit too operatic for her own good.

Fair enough, the length is problematic, and a whole lot of the second hour is just plain repetition. And there is no doubt that asking a modern viewer to sit still for 4.5 hours of silent melodrama because it's incredibly historically important is asking a lot. Yet there is more than just historic interest to make the film great; Gance's command of cinematic vocabulary is simply breathtaking, and even though it might not be the easiest or most fun film to watch, it is unquestionably required viewing for anyone who cares about the development of movies as a form of communication.

The new DVD runs at just a bit less than 4.5 hours, and according to the extensive booklet, it was edited together from five sources: a 35mm print of the 12-reel version, a 35mm Russian print of the eight-reel version, two incomplete 35mm prints from France and a small number of critical scenes from a 9.5mm French home edition. Those looking for a pristine image will be well-advised to look elsewhere; those numerous copies don't all have the same level of quality, and sometimes it's really hard to ignore that. The triumph of this DVD is that it exists at all; not every aspect of its presentation is flawless, chiefly relating to intertitles (the original French titles were often superimposed directly over the picture; a significant advance in 1922). I assume this is an unavoidable by-product of working with French and Russian prints, and at any rate a copy of La roue that is corrupt for a small percentage of its running time is much, much better than no copy of La roue at all.

To reduce the film to its barest elements of story, a melodrama like your grandma used to make, La roue is about Sisif (Séverin-Mars, who died before the picture's release), the finest train engineer in France, who we first meet as he helps to rescue the survivors of an apocalyptic train crash. One of those victims is a little English girl identified only as "Norma," whom Sisif adopts as the little sister to his motherless son Elie. 15 years later, Sisif is still the king of the engineers, Elie (Gabriel de Gravone) is a violin maker searching for an important historical varnish formula, and Norma (Ivy Close) is the beautiful "Rose of the Rails," a darling child who delights everyone that meets her. By this point, Sisif has fallen in love with her, Elie (not knowing that they are not related) is trying to ignore the fact that he is in love with her, and Norma, dimly aware that her presence is causing her father much torment, agrees to marry the wealthy stranger Jacques de Hersan (Pierre Magnier). Sisif is increasingly agitated by this, and when an accident robs him of much of his eyesight, his superiors jump on the excuse to banish him to a rickety train high in the Alps.

That's not a story that can support a 4.5 hour presentation, let alone 7.5 hours, but that's absolutely not the reason Gance made the film. High on the success of the WWI drama J'accuse!, he explicitly conceived of its mammoth follow-up to be an exploration of the art of cinema in all its totality, one of those things that you got to do back in the silent era when the art of cinema was younger than many of its practitioners. Like Griffith's Birth of a Nation seven years prior or Murnau's Sunrise five years later, La roue is nothing less than a snapshot of everything that could be achieved in the form at the time of its creation, and the progenitor of many of the techniques that are still used eight decades on. It's perfectly fair to call it one of the ten most influential and important films ever created, and this is why its new release is so welcome; as the DVD cover crows, no less a figure than Jean Cocteau once claimed "There is the cinema before and after La roue as there is painting before and after Picasso."

The challenge to the modern viewer is that, much as is the case with Birth of a Nation, the film was so successful in its attempts to create a new language that we don't really respect it the way we should, because that's the language we've grown up with. It's easy to say of the Griffith film that it's just a racist adventure movie, not thinking that in 1915, the idea of cutting between two concurrent plotlines was radicalism like most of us cannot imagine; so too in La roue do the editing and cinematography seem needlessly familiar. That's because there has been no reason to improve upon the perfection that La roue created more or less out of whole cloth.

In the DVD liner notes, the claim is made that La roue invented the cross-dissolve; I am not certain that it was the first film released with that technique, but its long production time might well mean that Gance and his cameramen (Dissolves had to be done in-camera back then! The mind reels) came up with the idea before anybody else. Think about that for a second: the dissolve from one scene to another is such a familiar trick that some of us find it to be cheap and tasteless - maybe that's just me - but in 1922, it was brand new. Admittedly, some of the film's most impressive technical leaps are even less interesting to the modern viewer: the use of shocking, bold colors for the tinted scenes is unlike anything I've ever seen, and I cannot think of another movie with such a mature and elaborate system of iris shots (the "pinhole camera" frame) in any other film, but these are both techniques that were essentially dead after the coming of sound. I might also point out that, filming in the studio but also in Nice and at the peak of Mount Blanc, this is one of the earliest and probably the most ambitious of all location shoots in film history, beating John Ford's mythic The Iron Horse to the punch by two years.

These mere historic notes are of course just a part of the film's aesthetic success: it is by any possible yardstick a brilliant-constructed film. "The wheel" it is called, with many great writers quoted where they referred to life's shifting fortunes and failures as a wheel, and rarely has a film's title been used to such effect in the film's visual scheme. Circles dominate La roue, from the wheels of trains in the Nice trainyard to the dance-in-the-round on the plateau of Mount Blanc that closes out the film. Even the iris shots that are used so bravely in the film are an extension of this idea: what is an iris but a circle closing in on the protagonist, cutting him off from the world around? Then there is the matter of the editing, a process which took Gance more than a year to complete, and such editing it is! Tied often to the rhythm of the train's movement, frequently breaking down into a series of shots that last only a frame or two, for several seconds at a time, La roue has the breathless pace of a music video 60 years ahead of time.

It's flaws, however, are not minor, though they are entirely limited to the film's success as a story. I don't mean the length; no good movie is ever too long, and at 4.5 hours, we're just barely getting to know Sisif well by the time we have to leave his company. Rather, the acting is a bit overripe even by the giant standards of the '20s - Séverin-Mars is at his best early and late in the film, when his chest-pounding angst over his lust towards Norma is the least pronounced, but de Gravone, besides being ten years too old for his part, is limp and unpleasant throughout. In the small role of the comic sidekick Machefer, Georges Térof turns the goggle-eyed shock so common in French silent comedy into something actually funny. But the absolute standout is Close, the only significant actor who never feels a bit too operatic for her own good.

Fair enough, the length is problematic, and a whole lot of the second hour is just plain repetition. And there is no doubt that asking a modern viewer to sit still for 4.5 hours of silent melodrama because it's incredibly historically important is asking a lot. Yet there is more than just historic interest to make the film great; Gance's command of cinematic vocabulary is simply breathtaking, and even though it might not be the easiest or most fun film to watch, it is unquestionably required viewing for anyone who cares about the development of movies as a form of communication.