Foot(ball) in mouth

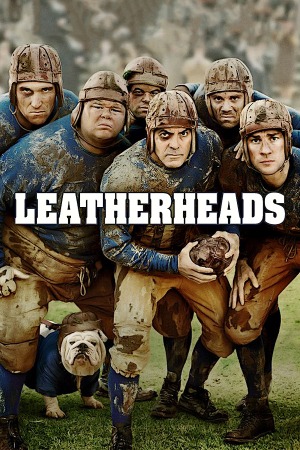

Writing a lukewarm review of Leatherheads has to count as my first truly heartbreaking disappointment of the movie year. George Clooney starring in and directing an homage to the screwball comedies of the 1930s was the sort of high concept that's had me drooling ever since the film was first pushed back five or six months ago. The end result is just too drowsy for its own good, less an homage and more a terribly slowed-down retread of some of the tropes from that genre buried underneath mannered performances and a storyline prone to needless detours into drama and historical analysis. I'd say that just under half of the film gets it right, a quarter almost reaches its goal, and a quarter is aimless and lazy and not at all funny.

In the interest of fairness, and the fact that I desperately want to like the movie more than I do, let's begin with the best stuff. The director's third film is also his third exercise in recreating a bygone time period, and as a recreation of the Midwest in 1925, it's a rousing success. Designed by James D. Bissell - an Oscar nominee for his exceptional work remaking the '50s in Clooney's Good Night, and Good Luck. - the film has something really special going with its look. Not having been alive 83 years ago, I can't really make claims about its veracity, but the film is packed to the gills with old-fashioned trains and cigarette advertisements, muddy football fields and the skyline of Chicago back in her youth, and it feels as much like a dream of the '20s as the real thing, but it's exceptionally appealing to look at. And while I'm right there, a round of applause to costume designer Louise Frogley (also a veteran of GN&GL), whose recreations of vintage sports uniforms add some flavor to the expected flapper-era fashions.

The film's look is aided, quite a lot, by Randy Newman's peppy ragtime-inflected score. Of course, Newman's music often sounds a bit ragtime-inflected (such as his soundtrack for the movie Ragtime), and it's not nearly his best work in the idiom. Not to mention that rag was a bit dead by the '20s, but it worked pretty damn well for The Sting, and it works pretty damn well here at creating a certain old-timey mood that contributes to that same dreamy sense of the era.

That's about as far as "recreating the '20s" will take us. The cinematography by the perpetually under-appreciated Newton Thomas Sigel (who did not shoot GN&GL, although he did shoot Clooney's debut, Confessions of a Dangerous Mind) can hardly be said to recreate the look of the decade, given that all of the movies and the vast number of still photographs from that time are in black and white, and Leatherheads is in a perpetually sepia-tinged color. There's no doubt that the film looks aged, but it's not the kind of aging that specifically dates the film. Rather, it's a shorthand for warm and romantic nostalgia, and the very notion of recreating a '30s screwball is nothing if it's not romantically nostalgic. Periodically, the film is interrupted by still photo montages of the characters in monochromatic sepia, and while the conceit is of debatable narrative value, the way it combines the cinematography and the production design is altogether, undeniably effective.

And then there's the man himself, George Clooney in his first self-directed leading role as Dodge Connelly, the middle-aged captain of the Duluth Bulldogs pro football team, a man who finds himself thrust into the center of a tug-of-war that would end in the creation of a national rulebook for the game and ultimately the creation of the national leagues and teams that we still know and love (it should be noted that the film has its history a bit confused: the NFL was named in 1922, having been original created as the American Professional Football Association two years prior). The role, a sports booster and diplomat, is essentially that of a flimflam man, the very sort of role that Clooney does better than anyone else in the modern cinema (in the mind at least of this reviewer, who considers the actor's best single performance to be the fast talking con in O Brother, Where Art Thou?). He does not disappoint here: as the only member of the cast to regularly draw comparisons to the movie stars of the '30s and '40s, it's fitting that he is perhaps the only actor who really seems to dig into the fast-talking, hyperneurotic mode of the screwball genre. It's really a fantastic, energetic, entertaining performance, that deserves a better project around it.

Yeah, the nice part is over now. The rest of the cast isn't nearly up to Clooney's level, with the possible exception of Stephen Root as Suds, the drunken newspaperman in Dodge's back pocket (I've just had a moment of clarity: Root was also in O Brother. My new rule: the Coen Brothers have a stranglehold on what makes good neo-screwball). The co-leads certainly can't hold their own: John Krasinski is given perilously little interesting to say or do as the college phenom and war hero who becomes Dodge's savior, then his romantic rival, then his enemy, and while I'm pleased to see he can do something that isn't Jim from The Office (his last feature, License to Wed, suggest no such versatility), his role is what we might call "The Ralph Bellamy," and anyone who is familiar with Bellamy's work as the perpetual other man knows that it's not exactly the sort of thing that lets an actor shine. Meanwhile, the romantic lead is Renée Zellweger, once a promising comedienne whose persona has grown increasingly stale and whose monolithic lack of expression besides her trademark squint is the very death of a role clearly written in the vein of Rosalind Russell's newswoman on speed from His Girl Friday. Zellweger already proved in Chicago that she didn't really know how to handle the peppery rat-a-tat dialogue of a sarcastic comedy, and in Leatherheads she does it again: her delivery is rounded and ambling, and she eases her lines out rather than firing them off, and the film slows down perceptibly every time she's onscreen.

Not that the script Zellweger can't get around is really all that deserving of a great actress. I don't quite know what to make of it: the sole feature written by Duncan Bradley and Rick Reilly, well over a decade ago, allegedly re-written almost entirely by Clooney, it feels like somebody who has read a hell of a lot about screwball comedies but never actually saw them. Sometimes, it's damn near perfect, especially in the first act when the exposition is covered up in a lot of blissfully funny scenes of life on the road in pre-Depression America. Sometimes, it falls to the ground with a clamor, as in almost all of the scenes revolving around Jonathan Pryce's as the startlingly uncomic scheming agent C.C. Frazier, when the mechanics of the plot kick in and laughs sit patiently and wait for the next goofy bit to happen. Most of it falls in between, with lines that are so close to witty that you can almost see the shape of it, but settle instead for cute at best, bland at worst.

It would be easy to like the film if it could just be appreciated as a comedy set in the 1920s, and not a remake of the screwball style (God knows we're not deluged with movie comedies that even brush against wit), but everything about the film is much too stylised to possibly ignore the film's many precursors and all the ways it falls shy of them. There is no "non-screwball" version of Leatherheads, because it wants so very badly to be that kind of comedy, it locks out any more prosaic reading. I have to confess, I admire Clooney for making the attempt, and still ending up with something a lot more fun to watch than the factory-produced romcoms that are what we have in place of actual comedies for the most part. But I would have admired him even more if he'd succeeded.

6/10

In the interest of fairness, and the fact that I desperately want to like the movie more than I do, let's begin with the best stuff. The director's third film is also his third exercise in recreating a bygone time period, and as a recreation of the Midwest in 1925, it's a rousing success. Designed by James D. Bissell - an Oscar nominee for his exceptional work remaking the '50s in Clooney's Good Night, and Good Luck. - the film has something really special going with its look. Not having been alive 83 years ago, I can't really make claims about its veracity, but the film is packed to the gills with old-fashioned trains and cigarette advertisements, muddy football fields and the skyline of Chicago back in her youth, and it feels as much like a dream of the '20s as the real thing, but it's exceptionally appealing to look at. And while I'm right there, a round of applause to costume designer Louise Frogley (also a veteran of GN&GL), whose recreations of vintage sports uniforms add some flavor to the expected flapper-era fashions.

The film's look is aided, quite a lot, by Randy Newman's peppy ragtime-inflected score. Of course, Newman's music often sounds a bit ragtime-inflected (such as his soundtrack for the movie Ragtime), and it's not nearly his best work in the idiom. Not to mention that rag was a bit dead by the '20s, but it worked pretty damn well for The Sting, and it works pretty damn well here at creating a certain old-timey mood that contributes to that same dreamy sense of the era.

That's about as far as "recreating the '20s" will take us. The cinematography by the perpetually under-appreciated Newton Thomas Sigel (who did not shoot GN&GL, although he did shoot Clooney's debut, Confessions of a Dangerous Mind) can hardly be said to recreate the look of the decade, given that all of the movies and the vast number of still photographs from that time are in black and white, and Leatherheads is in a perpetually sepia-tinged color. There's no doubt that the film looks aged, but it's not the kind of aging that specifically dates the film. Rather, it's a shorthand for warm and romantic nostalgia, and the very notion of recreating a '30s screwball is nothing if it's not romantically nostalgic. Periodically, the film is interrupted by still photo montages of the characters in monochromatic sepia, and while the conceit is of debatable narrative value, the way it combines the cinematography and the production design is altogether, undeniably effective.

And then there's the man himself, George Clooney in his first self-directed leading role as Dodge Connelly, the middle-aged captain of the Duluth Bulldogs pro football team, a man who finds himself thrust into the center of a tug-of-war that would end in the creation of a national rulebook for the game and ultimately the creation of the national leagues and teams that we still know and love (it should be noted that the film has its history a bit confused: the NFL was named in 1922, having been original created as the American Professional Football Association two years prior). The role, a sports booster and diplomat, is essentially that of a flimflam man, the very sort of role that Clooney does better than anyone else in the modern cinema (in the mind at least of this reviewer, who considers the actor's best single performance to be the fast talking con in O Brother, Where Art Thou?). He does not disappoint here: as the only member of the cast to regularly draw comparisons to the movie stars of the '30s and '40s, it's fitting that he is perhaps the only actor who really seems to dig into the fast-talking, hyperneurotic mode of the screwball genre. It's really a fantastic, energetic, entertaining performance, that deserves a better project around it.

Yeah, the nice part is over now. The rest of the cast isn't nearly up to Clooney's level, with the possible exception of Stephen Root as Suds, the drunken newspaperman in Dodge's back pocket (I've just had a moment of clarity: Root was also in O Brother. My new rule: the Coen Brothers have a stranglehold on what makes good neo-screwball). The co-leads certainly can't hold their own: John Krasinski is given perilously little interesting to say or do as the college phenom and war hero who becomes Dodge's savior, then his romantic rival, then his enemy, and while I'm pleased to see he can do something that isn't Jim from The Office (his last feature, License to Wed, suggest no such versatility), his role is what we might call "The Ralph Bellamy," and anyone who is familiar with Bellamy's work as the perpetual other man knows that it's not exactly the sort of thing that lets an actor shine. Meanwhile, the romantic lead is Renée Zellweger, once a promising comedienne whose persona has grown increasingly stale and whose monolithic lack of expression besides her trademark squint is the very death of a role clearly written in the vein of Rosalind Russell's newswoman on speed from His Girl Friday. Zellweger already proved in Chicago that she didn't really know how to handle the peppery rat-a-tat dialogue of a sarcastic comedy, and in Leatherheads she does it again: her delivery is rounded and ambling, and she eases her lines out rather than firing them off, and the film slows down perceptibly every time she's onscreen.

Not that the script Zellweger can't get around is really all that deserving of a great actress. I don't quite know what to make of it: the sole feature written by Duncan Bradley and Rick Reilly, well over a decade ago, allegedly re-written almost entirely by Clooney, it feels like somebody who has read a hell of a lot about screwball comedies but never actually saw them. Sometimes, it's damn near perfect, especially in the first act when the exposition is covered up in a lot of blissfully funny scenes of life on the road in pre-Depression America. Sometimes, it falls to the ground with a clamor, as in almost all of the scenes revolving around Jonathan Pryce's as the startlingly uncomic scheming agent C.C. Frazier, when the mechanics of the plot kick in and laughs sit patiently and wait for the next goofy bit to happen. Most of it falls in between, with lines that are so close to witty that you can almost see the shape of it, but settle instead for cute at best, bland at worst.

It would be easy to like the film if it could just be appreciated as a comedy set in the 1920s, and not a remake of the screwball style (God knows we're not deluged with movie comedies that even brush against wit), but everything about the film is much too stylised to possibly ignore the film's many precursors and all the ways it falls shy of them. There is no "non-screwball" version of Leatherheads, because it wants so very badly to be that kind of comedy, it locks out any more prosaic reading. I have to confess, I admire Clooney for making the attempt, and still ending up with something a lot more fun to watch than the factory-produced romcoms that are what we have in place of actual comedies for the most part. But I would have admired him even more if he'd succeeded.

6/10