European vacation

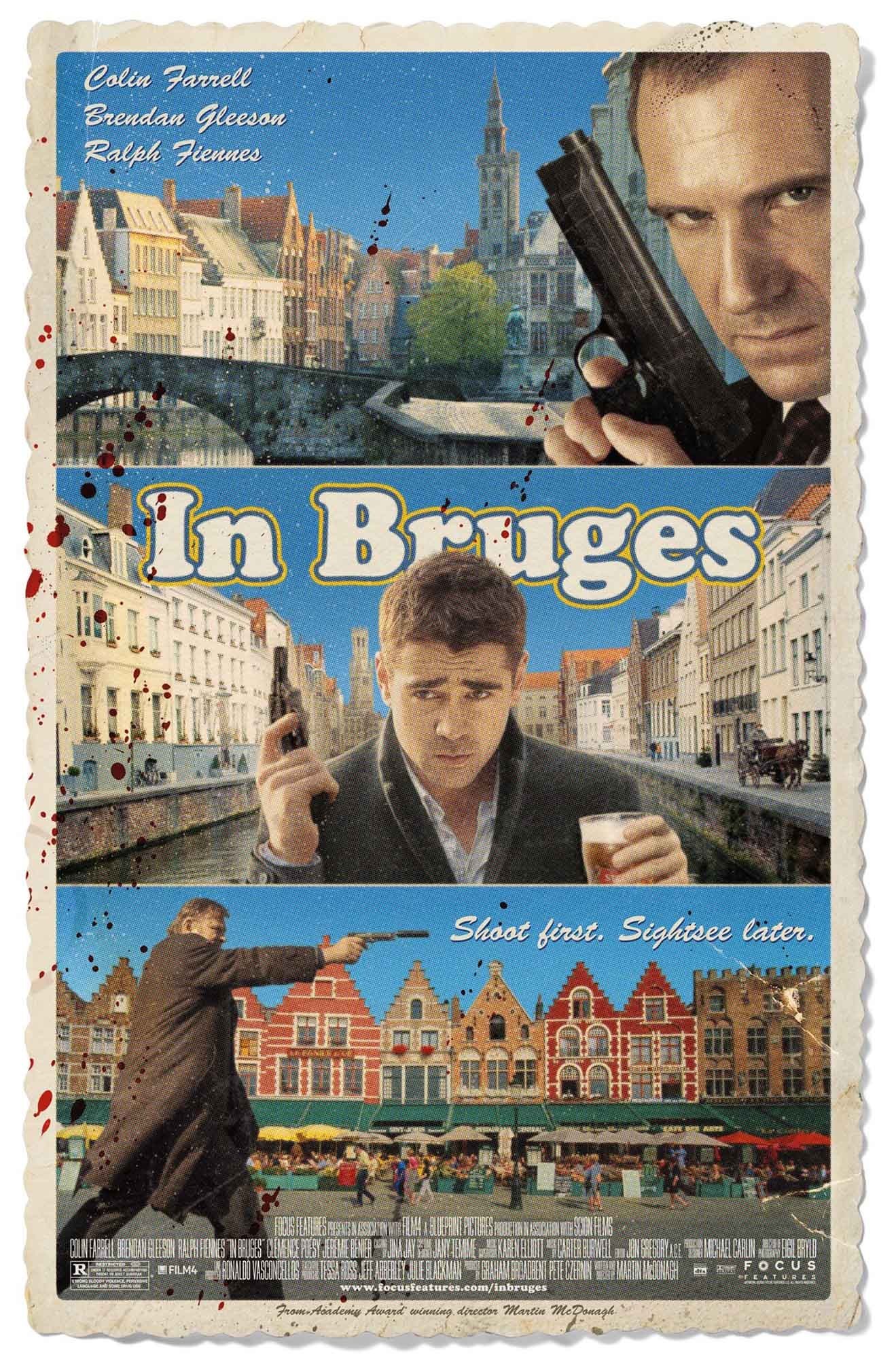

In Bruges is the first feature-length movie to be written and directed by Martin McDonagh, one of the key English language playwrights of the last 15 years. This leads me to two competing thoughts:

-Everything about In Bruges is explained by the fact its creator is based in theater.

-Nothing about In Bruges suggests that its creator hasn't been making movies for years.

Without getting too deep into all that so soon, though, let me open by saying instead: In Bruges is a near-masterpiece, impossible to pigeonhole or predict. It is the kind of great movie that could only be made by a neophyte: not only is the whole film blissed-out on just how much fun it is to make a movie, some of its best moments are the ones that could only have been carried off by a director who has never been told what not to do.

The film opens on two Irish hitmen hiding out in Bruges, Belgium: Ray (Colin Farrell) and Ken (Brendan Gleeson). It is not such an easy thing to explain much of the plot beyond that without giving things away that are better left to the viewer's discovery, for the story does not advance according to the usual rules of cinematic drama: a situation is established, the stakes are presented, conflict is introduced and then brought to a boil, all things are resolved either to the protagonist's satisfaction or disappointment. In Bruges follows the structure, instead, of a play (or at least, of McDonagh's plays): three acts, just like the standard Hollywood model likes, but the three acts do not refer to the development of a single conflict. Rather, each act is its own series of stakes and conflicts. The matter of the first half hour leads into the matter of the final half hour, but they are not the same; the conflicts we watch battling out in the first act are replaced by new conflicts, involving different aspects of the same characters.

That's the key to the whole script, that word "characters." For all that it is stuffed about as full of plot twists and diversions as you could manage in a fairly short running time, plot ends up mattering a whole lot less than how the plot reveals the characters in the film. A lot of movies are called "character studies," but not many of them actually fit that bill; the history of narrative cinema demands characters that propel themes or characters that propel plot, not the other way around. That's the chief benefit of letting a playwright make a movie, assuming you do consider that a benefit. It's a film where the chief thing that matters is that at the end we know who the characters are; not what they've learned about life (that would be a thematic issue), just who they are.

Since that is the whole point of the screenplay, it would be unbecoming of me to say any more than that. Let me just note that the film opens with a simple, buddy comedy type of conflict: Ray and Ken have been sent to Bruges for two weeks to hide out on the authority of gang boss Harry (Ralph Fiennes), for reasons that become clear much later on, with great elegance. Ken is the dutiful tourist, absorbing all of the facts from the guidebooks about the old buildings and canals. Ray, meanwhile, is incredibly miserable, finding Bruges to be totally devoid of anything bearing even a spark of life, except for his childlike glee at watching a movie shoot, where a dwarf (Jordan Prentice) is starring in a dream sequence in an homage to Nicolas Roeg's Don't Look Now, while a gorgeous drug dealer named Chloë (Clémence Poésy) sells to the cast and crew. Ken is generally happy to be alive and in Bruges; Ray is well on the way to full-fledged depression. For most of the film's first third, they wander through the city and exchange barbs and thoughts on life.

The film shoot seems at first like an unnecessary side-trip, a sub-Felliniesque collection of absurdities and grotesques. But it's a little deeper than that: the only time that Ray is ever completely excited by Bruges is when he realises that there's a movie being filmed with a midget. There are a couple things going on here; the most obvious is that throughout the film, Ray is a bit of a bigot, making fun of fat people, mentally retarded people, non-white people, women, and in one particular stroke, fat-retarded-black-women. He's casually biased against everyone not exactly like he is, and his delight at the little person is a reflection of that.

But I'd like to argue, whether intentionally or not, the scene also suggest McDonagh's state of mind, and his own enthusiasm for shooting a movie in Bruges. The director has stated flat out that the character's boredom in the city is a reflection of his own experience, and I'll concede that. Which still leaves the simple fact of shooting a movie: something McDonagh has only done once, in the 2004 short film Six Shooter". I'd like to imagine that in Ray's enthusiasm, McDonagh is admitting that movie sets, on the whole, are rather exciting places to be, for a newbie.

That enthusiasm for the filmmaking process is just about the only way I can explain the feeling of In Bruges, which is plainly the work of a director who is really happy to be where he is. It's not unlike the early work of Tarantino: as much of the film is clever visual and stylistic references to other films as not, and it's clear that the man who put this all together was making a film he wanted to see. This could leave the film feeling overstuffed; there's a fine line between having a lot of ideas and having no discipline - McDonagh occasionally drifts towards a lack of discipline, but it's hard to argue that he ever does anything arbitrarily or randomly. Every shot, more or less, contributes to the flow of the film, and it's clear that the director has one of the most important filmmaking skills: a good sense of pace and timing. At any rate, he's clearly much more aware of how this camera angle or that cut functions as part of cinema's visual language than the author he has frequently been compared to, David Mamet, whose work as a movie director tends to suggest a small but certain degree of contempt for filmmaking.

To a degree, In Bruges is just as exciting because it speaks to an exciting future career for McDonagh as because of anything that the film actually achieves. It is not his best work as a writer, certainly, though it is evocative of what makes his writing work - aggressive and uncomfortable language, comedy that shifts into drama without the audience ever noticing - and it's scale is unmistakably that of a movie, not of a play. Unsurprisingly for a theater writer, he proves to have a great rapport with actors - Farrell has absolutely never been better, and Gleeson and Fiennes are certainly both extremely good. It's not a film that redefines the art, but it's immensely entertaining and well-crafted, and it has a deep and unmistakable humanity that leaves it much more unexpectedly meaningful than a story about two gangsters vacationing in Europe has any real reason to be.

-Everything about In Bruges is explained by the fact its creator is based in theater.

-Nothing about In Bruges suggests that its creator hasn't been making movies for years.

Without getting too deep into all that so soon, though, let me open by saying instead: In Bruges is a near-masterpiece, impossible to pigeonhole or predict. It is the kind of great movie that could only be made by a neophyte: not only is the whole film blissed-out on just how much fun it is to make a movie, some of its best moments are the ones that could only have been carried off by a director who has never been told what not to do.

The film opens on two Irish hitmen hiding out in Bruges, Belgium: Ray (Colin Farrell) and Ken (Brendan Gleeson). It is not such an easy thing to explain much of the plot beyond that without giving things away that are better left to the viewer's discovery, for the story does not advance according to the usual rules of cinematic drama: a situation is established, the stakes are presented, conflict is introduced and then brought to a boil, all things are resolved either to the protagonist's satisfaction or disappointment. In Bruges follows the structure, instead, of a play (or at least, of McDonagh's plays): three acts, just like the standard Hollywood model likes, but the three acts do not refer to the development of a single conflict. Rather, each act is its own series of stakes and conflicts. The matter of the first half hour leads into the matter of the final half hour, but they are not the same; the conflicts we watch battling out in the first act are replaced by new conflicts, involving different aspects of the same characters.

That's the key to the whole script, that word "characters." For all that it is stuffed about as full of plot twists and diversions as you could manage in a fairly short running time, plot ends up mattering a whole lot less than how the plot reveals the characters in the film. A lot of movies are called "character studies," but not many of them actually fit that bill; the history of narrative cinema demands characters that propel themes or characters that propel plot, not the other way around. That's the chief benefit of letting a playwright make a movie, assuming you do consider that a benefit. It's a film where the chief thing that matters is that at the end we know who the characters are; not what they've learned about life (that would be a thematic issue), just who they are.

Since that is the whole point of the screenplay, it would be unbecoming of me to say any more than that. Let me just note that the film opens with a simple, buddy comedy type of conflict: Ray and Ken have been sent to Bruges for two weeks to hide out on the authority of gang boss Harry (Ralph Fiennes), for reasons that become clear much later on, with great elegance. Ken is the dutiful tourist, absorbing all of the facts from the guidebooks about the old buildings and canals. Ray, meanwhile, is incredibly miserable, finding Bruges to be totally devoid of anything bearing even a spark of life, except for his childlike glee at watching a movie shoot, where a dwarf (Jordan Prentice) is starring in a dream sequence in an homage to Nicolas Roeg's Don't Look Now, while a gorgeous drug dealer named Chloë (Clémence Poésy) sells to the cast and crew. Ken is generally happy to be alive and in Bruges; Ray is well on the way to full-fledged depression. For most of the film's first third, they wander through the city and exchange barbs and thoughts on life.

The film shoot seems at first like an unnecessary side-trip, a sub-Felliniesque collection of absurdities and grotesques. But it's a little deeper than that: the only time that Ray is ever completely excited by Bruges is when he realises that there's a movie being filmed with a midget. There are a couple things going on here; the most obvious is that throughout the film, Ray is a bit of a bigot, making fun of fat people, mentally retarded people, non-white people, women, and in one particular stroke, fat-retarded-black-women. He's casually biased against everyone not exactly like he is, and his delight at the little person is a reflection of that.

But I'd like to argue, whether intentionally or not, the scene also suggest McDonagh's state of mind, and his own enthusiasm for shooting a movie in Bruges. The director has stated flat out that the character's boredom in the city is a reflection of his own experience, and I'll concede that. Which still leaves the simple fact of shooting a movie: something McDonagh has only done once, in the 2004 short film Six Shooter". I'd like to imagine that in Ray's enthusiasm, McDonagh is admitting that movie sets, on the whole, are rather exciting places to be, for a newbie.

That enthusiasm for the filmmaking process is just about the only way I can explain the feeling of In Bruges, which is plainly the work of a director who is really happy to be where he is. It's not unlike the early work of Tarantino: as much of the film is clever visual and stylistic references to other films as not, and it's clear that the man who put this all together was making a film he wanted to see. This could leave the film feeling overstuffed; there's a fine line between having a lot of ideas and having no discipline - McDonagh occasionally drifts towards a lack of discipline, but it's hard to argue that he ever does anything arbitrarily or randomly. Every shot, more or less, contributes to the flow of the film, and it's clear that the director has one of the most important filmmaking skills: a good sense of pace and timing. At any rate, he's clearly much more aware of how this camera angle or that cut functions as part of cinema's visual language than the author he has frequently been compared to, David Mamet, whose work as a movie director tends to suggest a small but certain degree of contempt for filmmaking.

To a degree, In Bruges is just as exciting because it speaks to an exciting future career for McDonagh as because of anything that the film actually achieves. It is not his best work as a writer, certainly, though it is evocative of what makes his writing work - aggressive and uncomfortable language, comedy that shifts into drama without the audience ever noticing - and it's scale is unmistakably that of a movie, not of a play. Unsurprisingly for a theater writer, he proves to have a great rapport with actors - Farrell has absolutely never been better, and Gleeson and Fiennes are certainly both extremely good. It's not a film that redefines the art, but it's immensely entertaining and well-crafted, and it has a deep and unmistakable humanity that leaves it much more unexpectedly meaningful than a story about two gangsters vacationing in Europe has any real reason to be.

Categories: british cinema, gangster pictures, top 10