A critique of pure cinema

The hype was right. No Country for Old Men is basically flawless.

Scrupulously adapted from Cormac McCarthy's 2005 novel, frequently called "minor" on the apparent grounds that it is one of the author's easiest books to read, the film represents a roaring return for filmmakers Joel and Ethan Coen to the mode of their heyday, particularly their debut Blood Simple and Fargo, perhaps their best-received work. Like those two projects, No Country is a meditation on violence and the search for moral order in modern America, although neither of those earlier films reached for the same apocalyptic scope - and please, let's not get into the messy business of ranking them; ask me after ten years and another half-dozen viewings if No Country is their "best."

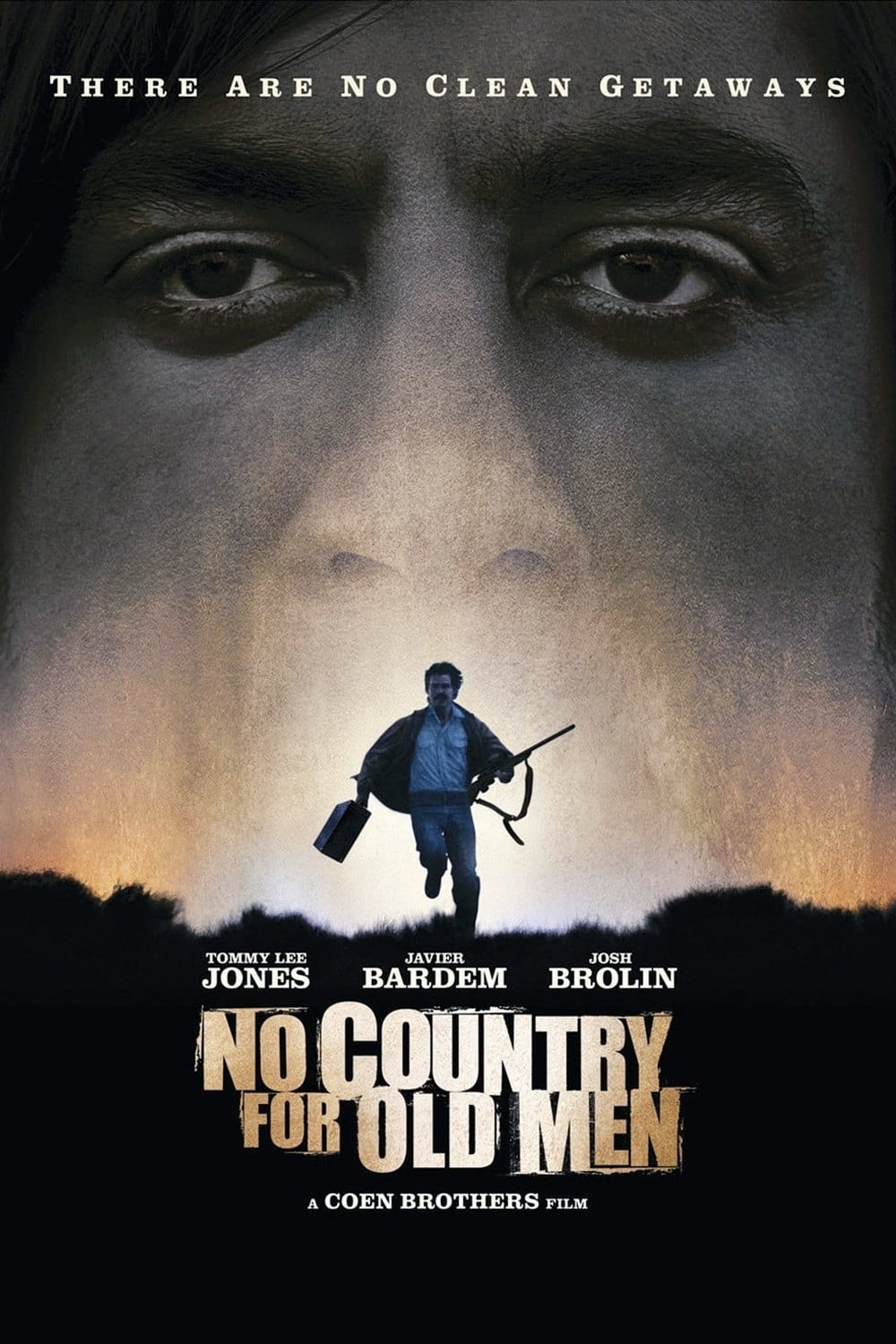

Of the brothers' canon, perhaps only Barton Fink achieves a comparable level of destructive power, and there only in the hallucinatory final act. In contrast, No Country is for nearly its entire two hours a voyage through hell on earth, pitting a weak man of Good against a force of incomprehensible evil, with a deeply ambiguous man in the center. The story follows Llewelyn Moss (Josh Brolin), who finds a satchel with $2 million in the bloody aftermath of a drug bust gone wrong, the psychopathic Anton Chigurh (Javier Bardem), tasked with retrieving the money, and aging Sheriff Ed Tom Bell (Tommy Lee Jones), trying to find both men before the trail of dead bodies in their wake grows any larger.

For a certainty, it's a well-told story, but I think I will not spend too much time digging into it; it is close enough to identical to the novel that it's not fair to credit the movie qua the movie with the moral and thematic development of the plot. Besides, plenty of other people have done that. Though, I would like to posit that the few changes to the story are all well-chosen, and make it more cinematic; that is, the book's narrative is great for a book, and the film's narrative, where it is different (primarily the streamlined ending), is great for a movie.

No, instead of talking about why this is a tremendously effective story about the fear of death and the fear of obsolescence, and the ways that those fears shade into one another, I'd like to talk, and by "talk" I mean, "rave fanboyishly," about the construction of the thing. I am after all an unrepentant forpipmalist, and the Coens are among the finest formal directors now working, and damn me if No Country for Old Men isn't just about the most exemplary work in their career.

There is, of course, the obvious stuff: and nothing about the film's aesthetic is more obvious than Roger Deakins's cinematography. The man is having a banner year: first In the Valley of Elah, then The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford. About that latter film, I proposed that it might be the "most beautiful" work of his career. I am willing to put away the qualifiers now: No Country represents the pinnacle of a career that has included such tours du camera as Fargo and Jarhead. If I may be so reductive, cinematography is at heart the art of telling a story using light and dark. There are such things as focus and composition, obviously, but in No Country, it is primarily Deakins's use of shadow, silhouette and harsh key lighting that create mood and atmosphere. Much of the film takes place at night, and so there are frequent pools of light and flashlights and the like used as spots of illumination in the darkness. Even during the daylight scenes, there are deep dark shadows cutting into the world (a phenomenal early example: the shadow of a cloud rolling over the landscape), and more than once in the film, the harsh desert sunlight gives way to a slab of interior blackness, most particularly in a scene near the end when one character is preparing to enter a room that he knows to house only death and danger. Basically, I mean to say that this is a dark film, even when it's nominally bright.

Then there is the editing, done by the Coens under the collective pseudonym "Roderick Jaynes." It's rather conspicuous, for those who like to look for such things, and it is powerful: one need look no further than the first ten minutes, for a scene in which Moss crawls through a dark killing field, and the cuts are precisely what is necessary to dial the tension up at a constant rate, culminating in the truly shocking moment when Moss glances over his shoulder to see the sudden appearance of the men who will in short order be making his life an endless chase.

And then (the problem with reviewing this film, for the enthusiast: the temptation to make the review a laundry list of what is awesome is nearly impossible to avoid. At any rate, I have elected not to avoid it), there is the soundscape. Sound is fundamentally one of those things that you just cannot explain - I went to film school for four years and I still have a hard time being any more specific than "that sounded cool." Let me content myself then by naming the designer, Craig Berkey, and the editor, Skip Lievsay (who has been with the brothers since Blood Simple); and let me argue vaguely that the sound in this film is brilliant and beyond brilliant, full of tiny noises amplified to great intensity, the seemingly constant undertone of the wind, and the subtle but persistent hiss of Chigurh's cattlegun.

But for all that, this is a Coen film, and what that means more than anything else is the precision of the world that it takes place in; not like Tim Burton or Terry Gilliam, a grotesque; nor like Tarantino, a day-glo pastiche of reality. The Coen mise en scène is and always has been a collection of tiny and perfectly realistic details building upon each other until a complete world has been established, almost identical to ours except for some details of quirk and character. A Coen film takes place in a very lived-in world, and in the case of No Country, that is a hazy mash-up of 1980 and today, with a rich superfluity of detail starting at the scuff marks which Chigurh's first victim leaves on a tile floor to the crowded old shack where Sheriff Bell fails to achieve the moral epiphany he so craves. In between, there is not a single shot that doesn't feel of a piece with the whole, a reality just a shade to the side of ours.

What else is there to say? Others have alternately praised and damned the film's ending as well as I could (for the record: I am in favor of the film's current ending, which manages to remain totally elliptical as it still ties off each and every loose end). There are the actors, who are as good as you've heard: Bardem in particular feels more like a force of nature than a character, the Glaswegian actress Kelly Macdonald disappears completely into the role of a nervous Texas housewife, and I am invariably charmed to see a Deadwood alum on the big screen, in this case Garret Dillahunt as Bell's second-in-command.

But I don't want to write the definitive No Country essay, if such a thing can exist. Plenty of words have already been spent on the film and plenty more will be spent. It's that kind of film. For my part, I am content at this moment to praise what I think is a flat-out masterpiece of the nuts-and-bolts craftsmanship that makes cinema unique. This is a movie in full.

Scrupulously adapted from Cormac McCarthy's 2005 novel, frequently called "minor" on the apparent grounds that it is one of the author's easiest books to read, the film represents a roaring return for filmmakers Joel and Ethan Coen to the mode of their heyday, particularly their debut Blood Simple and Fargo, perhaps their best-received work. Like those two projects, No Country is a meditation on violence and the search for moral order in modern America, although neither of those earlier films reached for the same apocalyptic scope - and please, let's not get into the messy business of ranking them; ask me after ten years and another half-dozen viewings if No Country is their "best."

Of the brothers' canon, perhaps only Barton Fink achieves a comparable level of destructive power, and there only in the hallucinatory final act. In contrast, No Country is for nearly its entire two hours a voyage through hell on earth, pitting a weak man of Good against a force of incomprehensible evil, with a deeply ambiguous man in the center. The story follows Llewelyn Moss (Josh Brolin), who finds a satchel with $2 million in the bloody aftermath of a drug bust gone wrong, the psychopathic Anton Chigurh (Javier Bardem), tasked with retrieving the money, and aging Sheriff Ed Tom Bell (Tommy Lee Jones), trying to find both men before the trail of dead bodies in their wake grows any larger.

For a certainty, it's a well-told story, but I think I will not spend too much time digging into it; it is close enough to identical to the novel that it's not fair to credit the movie qua the movie with the moral and thematic development of the plot. Besides, plenty of other people have done that. Though, I would like to posit that the few changes to the story are all well-chosen, and make it more cinematic; that is, the book's narrative is great for a book, and the film's narrative, where it is different (primarily the streamlined ending), is great for a movie.

No, instead of talking about why this is a tremendously effective story about the fear of death and the fear of obsolescence, and the ways that those fears shade into one another, I'd like to talk, and by "talk" I mean, "rave fanboyishly," about the construction of the thing. I am after all an unrepentant forpipmalist, and the Coens are among the finest formal directors now working, and damn me if No Country for Old Men isn't just about the most exemplary work in their career.

There is, of course, the obvious stuff: and nothing about the film's aesthetic is more obvious than Roger Deakins's cinematography. The man is having a banner year: first In the Valley of Elah, then The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford. About that latter film, I proposed that it might be the "most beautiful" work of his career. I am willing to put away the qualifiers now: No Country represents the pinnacle of a career that has included such tours du camera as Fargo and Jarhead. If I may be so reductive, cinematography is at heart the art of telling a story using light and dark. There are such things as focus and composition, obviously, but in No Country, it is primarily Deakins's use of shadow, silhouette and harsh key lighting that create mood and atmosphere. Much of the film takes place at night, and so there are frequent pools of light and flashlights and the like used as spots of illumination in the darkness. Even during the daylight scenes, there are deep dark shadows cutting into the world (a phenomenal early example: the shadow of a cloud rolling over the landscape), and more than once in the film, the harsh desert sunlight gives way to a slab of interior blackness, most particularly in a scene near the end when one character is preparing to enter a room that he knows to house only death and danger. Basically, I mean to say that this is a dark film, even when it's nominally bright.

Then there is the editing, done by the Coens under the collective pseudonym "Roderick Jaynes." It's rather conspicuous, for those who like to look for such things, and it is powerful: one need look no further than the first ten minutes, for a scene in which Moss crawls through a dark killing field, and the cuts are precisely what is necessary to dial the tension up at a constant rate, culminating in the truly shocking moment when Moss glances over his shoulder to see the sudden appearance of the men who will in short order be making his life an endless chase.

And then (the problem with reviewing this film, for the enthusiast: the temptation to make the review a laundry list of what is awesome is nearly impossible to avoid. At any rate, I have elected not to avoid it), there is the soundscape. Sound is fundamentally one of those things that you just cannot explain - I went to film school for four years and I still have a hard time being any more specific than "that sounded cool." Let me content myself then by naming the designer, Craig Berkey, and the editor, Skip Lievsay (who has been with the brothers since Blood Simple); and let me argue vaguely that the sound in this film is brilliant and beyond brilliant, full of tiny noises amplified to great intensity, the seemingly constant undertone of the wind, and the subtle but persistent hiss of Chigurh's cattlegun.

But for all that, this is a Coen film, and what that means more than anything else is the precision of the world that it takes place in; not like Tim Burton or Terry Gilliam, a grotesque; nor like Tarantino, a day-glo pastiche of reality. The Coen mise en scène is and always has been a collection of tiny and perfectly realistic details building upon each other until a complete world has been established, almost identical to ours except for some details of quirk and character. A Coen film takes place in a very lived-in world, and in the case of No Country, that is a hazy mash-up of 1980 and today, with a rich superfluity of detail starting at the scuff marks which Chigurh's first victim leaves on a tile floor to the crowded old shack where Sheriff Bell fails to achieve the moral epiphany he so craves. In between, there is not a single shot that doesn't feel of a piece with the whole, a reality just a shade to the side of ours.

What else is there to say? Others have alternately praised and damned the film's ending as well as I could (for the record: I am in favor of the film's current ending, which manages to remain totally elliptical as it still ties off each and every loose end). There are the actors, who are as good as you've heard: Bardem in particular feels more like a force of nature than a character, the Glaswegian actress Kelly Macdonald disappears completely into the role of a nervous Texas housewife, and I am invariably charmed to see a Deadwood alum on the big screen, in this case Garret Dillahunt as Bell's second-in-command.

But I don't want to write the definitive No Country essay, if such a thing can exist. Plenty of words have already been spent on the film and plenty more will be spent. It's that kind of film. For my part, I am content at this moment to praise what I think is a flat-out masterpiece of the nuts-and-bolts craftsmanship that makes cinema unique. This is a movie in full.