In the flesh

My first intention had been to start out with a little riff about being confused by how The Diving Bell and the Butterfly seems like it must be a biopic, but there are no musicians taking drugs, so it just can't be. But I decided that missed the point a little bit, and I would just be passive-aggressive about it. Anyway, it's not a biopic, not precisely. Like Capote, it tells a real story about a real person, but it's not really his life story so much as it is about one overriding incident in his life.

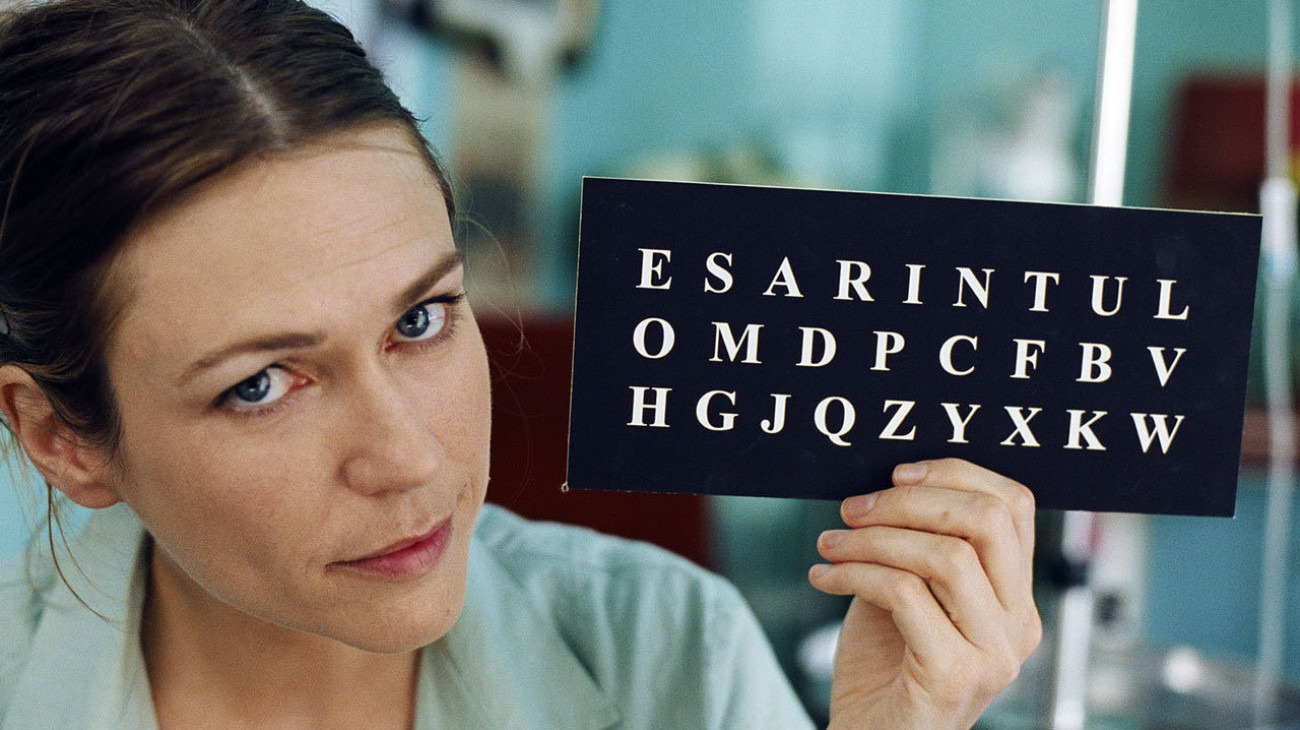

Quite the story it is, too: the French editor of Elle, Jean-Dominique Bauby, was 43 years old in 1995, when he suffered a massive stroke that for unclear reasons left his brainstem so damaged as to trap him with locked-in syndrome: a disease where the upper brain is perfectly intact and the voluntary muscle system is irretrievably dysfunctional. Bauby was able only to move his head a tiny bit, grunt a tiny bit, and blink his left eyelid; and it was by using this one ability that he could communicate in binary, more or less. A system was worked out whereby he would listen to an aide recite the alphabet, and he would blink when a letter was reached; thus could he tortuously spell out words, and thus did he endeavor to write a memoir about being trapped inside one's body, Le scaphandre et le papillon. The hugely successful book was published mere days before Bauby died of heart failure.

Whatever other flaws any particular adaptation of that book might have, the one that cannot possibly be overcome is that the most fascinating part of the story is that it exists in the first place. It's really just human nature: no matter how interesting the content of a book explaining how it feels to be locked-in (and it's pretty damned interesting, to my way of thinking), the fact that a locked-in man wrote a book in the first place is almost necessarily more interesting, because it includes the basic idea and then adds to it.

Of course, dramatising a book that takes place entirely in a single mind would be hell anyway, practically requiring the invention of a brand new cinematic language. But I don't care if Orson Welles and Krzysztof Kieślowski both returned from the dead to collaborate on developing that language, it still remains that their film would be essentially unable to be more compelling and fascinating and thought-provoking than the fact of the book.

That said, Welles and Kieślowski would probably not have come up with a much better approach to the material than the American avant-garde artist-turned-filmmaker Julian Schnabel. Not that he uses that approach flawlessly; and I suppose it's not right to call it a "brand new cinematic language," but he still comes up with a wholly successful patchwork of techniques with what I'm sure was a great deal of assistance from cinematographer Janusz Kamiński, noted Spielberg associate, turning in what is surely the most adventurous work of his career if not necessarily the most aesthetically satisfying.

What they do is shoot from Bauby's point-of-view, but it's more than just the simple "the camera is the character" sort of thing. Through the use of focus and lighting and movement, they suggest the vision of a man who's just had a stroke and can't quite see properly, who can't turn his head on his own, but who can dart around with his single good eye. I also do believe I detected the use of a wide lens (I've had a hell of a time confirming it) to sort of capture the entire human field of vision - wider than a film frame - and suggest that Bauby's ability to see has been "compressed" a little, forced into a narrower frame than it could fill.

Then there are the editing (by Juliette Welfling) and the sound (by Dominique Gaborieau and Francis Wargnier): the first capturing the ways that a man of Bauby's damaged brain might have a hard time retaining focus and consciousness, skipping like a cheap record player, the latter foregrounding the way that sounds inside the head are different to the ear than sounds outside the body. Since nearly everything Bauby feels must be communicated by narration, the proper sound design is crucial here.

I've made it sound like a dry academic exercise, but it's certainly not. It's completely engaging, in fact, by turns terrifying and humane and even funny. There is a huge problem with this aesthetic, though - for of course I cannot love a movie without finding a huge problem - and that is the way that Schnabel gets out of it. The majority of the film is not shot from inside Bauby's head, which is probably for the best, and when it is not it is still mostly good although a great deal more conventional: Mathieu Amalric, in a role that once was destined for Johnny Depp (and I think it's really for the best that it didn't work out that way), manages the superhuman task of communicating emotion using eye movement - in fact, I haven't the slightest hesitation in saying that Amalric is much more interesting when he plays the locked-in Bauby than he is during flashbacks. The supporting cast around him is extremely good, especially Max von Sydow, which you've probably heard by now, and Emmanuelle Seigner, which you probably haven't. Von Sydow plays Bauby's father in two scenes, and perhaps because of that ol' Swedish gravitas that he carries with him like its part of his body, he turns the film's most conspicuously Oscarbaity moment of manipulative tearjearking into an actual tearjerking scene. Seigner plays one of Bauby's ex-lovers, the mother of his children, still madly in love with him even as he sits mute, and the hurt that plays across her face is positively wounding.

It's pedestrian, I won't lie, but it's the kind of pedestrian that is still awfully emotionally effective. The problem getting to it at last, is that the rotation between the conventional "man trapped in a wheelchair" drama and the more avant-garde "inside a man's head as he is trapped in a wheelchair drama" seems completely arbitrary. I'd hoped that if I sat with the film for long enough - it's now been four days - I would have some sense of what made Schnabel choose the moments he did to switch perspective, and I simply can't. The best I can come up with is that he was afraid we'd get bored if he spent too long in either point-of-view.

That's not good enough. Everything about this story hinges on point-of-view to an exceptional degree: the story is notable primarily because of point-of-view. And as far as I can tell, there is no specific method to the director's manipulation between points-of-view besides whim. I would like very much to re-watch the film, actually, and try to see if I missed anything, but that's not an option open to me right now. So I just have to go with my gut reaction: a very good movie is mixed with a pretty good movie with such carelessness as to leave both of them much worse off. It's still a good movie. But it wanted very badly to be great.

Quite the story it is, too: the French editor of Elle, Jean-Dominique Bauby, was 43 years old in 1995, when he suffered a massive stroke that for unclear reasons left his brainstem so damaged as to trap him with locked-in syndrome: a disease where the upper brain is perfectly intact and the voluntary muscle system is irretrievably dysfunctional. Bauby was able only to move his head a tiny bit, grunt a tiny bit, and blink his left eyelid; and it was by using this one ability that he could communicate in binary, more or less. A system was worked out whereby he would listen to an aide recite the alphabet, and he would blink when a letter was reached; thus could he tortuously spell out words, and thus did he endeavor to write a memoir about being trapped inside one's body, Le scaphandre et le papillon. The hugely successful book was published mere days before Bauby died of heart failure.

Whatever other flaws any particular adaptation of that book might have, the one that cannot possibly be overcome is that the most fascinating part of the story is that it exists in the first place. It's really just human nature: no matter how interesting the content of a book explaining how it feels to be locked-in (and it's pretty damned interesting, to my way of thinking), the fact that a locked-in man wrote a book in the first place is almost necessarily more interesting, because it includes the basic idea and then adds to it.

Of course, dramatising a book that takes place entirely in a single mind would be hell anyway, practically requiring the invention of a brand new cinematic language. But I don't care if Orson Welles and Krzysztof Kieślowski both returned from the dead to collaborate on developing that language, it still remains that their film would be essentially unable to be more compelling and fascinating and thought-provoking than the fact of the book.

That said, Welles and Kieślowski would probably not have come up with a much better approach to the material than the American avant-garde artist-turned-filmmaker Julian Schnabel. Not that he uses that approach flawlessly; and I suppose it's not right to call it a "brand new cinematic language," but he still comes up with a wholly successful patchwork of techniques with what I'm sure was a great deal of assistance from cinematographer Janusz Kamiński, noted Spielberg associate, turning in what is surely the most adventurous work of his career if not necessarily the most aesthetically satisfying.

What they do is shoot from Bauby's point-of-view, but it's more than just the simple "the camera is the character" sort of thing. Through the use of focus and lighting and movement, they suggest the vision of a man who's just had a stroke and can't quite see properly, who can't turn his head on his own, but who can dart around with his single good eye. I also do believe I detected the use of a wide lens (I've had a hell of a time confirming it) to sort of capture the entire human field of vision - wider than a film frame - and suggest that Bauby's ability to see has been "compressed" a little, forced into a narrower frame than it could fill.

Then there are the editing (by Juliette Welfling) and the sound (by Dominique Gaborieau and Francis Wargnier): the first capturing the ways that a man of Bauby's damaged brain might have a hard time retaining focus and consciousness, skipping like a cheap record player, the latter foregrounding the way that sounds inside the head are different to the ear than sounds outside the body. Since nearly everything Bauby feels must be communicated by narration, the proper sound design is crucial here.

I've made it sound like a dry academic exercise, but it's certainly not. It's completely engaging, in fact, by turns terrifying and humane and even funny. There is a huge problem with this aesthetic, though - for of course I cannot love a movie without finding a huge problem - and that is the way that Schnabel gets out of it. The majority of the film is not shot from inside Bauby's head, which is probably for the best, and when it is not it is still mostly good although a great deal more conventional: Mathieu Amalric, in a role that once was destined for Johnny Depp (and I think it's really for the best that it didn't work out that way), manages the superhuman task of communicating emotion using eye movement - in fact, I haven't the slightest hesitation in saying that Amalric is much more interesting when he plays the locked-in Bauby than he is during flashbacks. The supporting cast around him is extremely good, especially Max von Sydow, which you've probably heard by now, and Emmanuelle Seigner, which you probably haven't. Von Sydow plays Bauby's father in two scenes, and perhaps because of that ol' Swedish gravitas that he carries with him like its part of his body, he turns the film's most conspicuously Oscarbaity moment of manipulative tearjearking into an actual tearjerking scene. Seigner plays one of Bauby's ex-lovers, the mother of his children, still madly in love with him even as he sits mute, and the hurt that plays across her face is positively wounding.

It's pedestrian, I won't lie, but it's the kind of pedestrian that is still awfully emotionally effective. The problem getting to it at last, is that the rotation between the conventional "man trapped in a wheelchair" drama and the more avant-garde "inside a man's head as he is trapped in a wheelchair drama" seems completely arbitrary. I'd hoped that if I sat with the film for long enough - it's now been four days - I would have some sense of what made Schnabel choose the moments he did to switch perspective, and I simply can't. The best I can come up with is that he was afraid we'd get bored if he spent too long in either point-of-view.

That's not good enough. Everything about this story hinges on point-of-view to an exceptional degree: the story is notable primarily because of point-of-view. And as far as I can tell, there is no specific method to the director's manipulation between points-of-view besides whim. I would like very much to re-watch the film, actually, and try to see if I missed anything, but that's not an option open to me right now. So I just have to go with my gut reaction: a very good movie is mixed with a pretty good movie with such carelessness as to leave both of them much worse off. It's still a good movie. But it wanted very badly to be great.