A little Wes

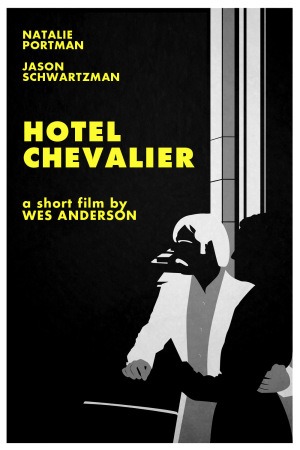

Wes Anderson, new media titan that he is, has released a short film unto the internets: Hotel Chevalier, the prologue to his about-to-open The Darjeeling Limited.

Short version: it's absolutely the best thing he's done since Rushmore (yes, even better than that extraordinary American Express ad from last year).

Long version: Anderson is nothing if not entrenched in his ways, and like so many filmmakers before him, it's when he stretches outside of his comfort zone that he becomes truly interesting. And by virtually any standard, "Hotel Chevalier" is his most original film ever (which basically means that it's ripping off Rohmer instead of Godard and Truffaut; I wonder if it's possible to make a movie about sex in Paris that doesn't rip off Rohmer?). At first it doesn't necessarily seem that way: there is as always the Andersonian fixation on exactly balanced compositions and claustrophobically specific color palettes, in this case yellow.

But dig in a bit, and it feels a little bit fresher: gone is the fussy production design of The Royal Tenenbaums and The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou, replaced by something that, by Anderson's standards, practically qualifies as minimalism. It reiterates something that has been easy to forget in the nine (!) years since Rushmore: Anderson's oh-so-formal compositions can be quite arresting when they're not aimed at obvious sets. Paris is a gorgeous city, but it's not often for it to have the geometric elegance that we see in the last few shots of Hotel Chevalier

And of course, there's the hatefucking.

Sex has been banished from the Wes Anderson universe 'til now, and for that matter, so has actual anger. Both are present - and how! - in this film, representing a new level of adult maturity that hasn't been in any of the director's frankly childlike films before. I think a large part of that can be credited to Natalie Portman: her acting style doesn't really fit in with the refined alienation that Anderson has brought in actors from Owen Wilson to Bill Murray to Anjelica Huston. Portman is much too physical and "present," if I can be a bit vague, to operate on that level of abstraction, and so much the better for her: she is an adult, come like an invading force into Anderson's hermetic world, and bringing with her emotional rawness that he has never ever touched upon before.

The film is a bit harsh, actually, and anti-romantic in a way that most American filmmakers don't even realise exists. That it has been filmed in the director's unmistakable idiom is jarring, but jarring in a way that shakes the staleness out of that style, and reminds us of what made it interesting in the first place: the way that it traps characters into formulaic modes of behavior that they cannot escape no matter how much they know that they are making terrible mistakes.

Anyway, don't listen to me. Just go watch the thing.

Short version: it's absolutely the best thing he's done since Rushmore (yes, even better than that extraordinary American Express ad from last year).

Long version: Anderson is nothing if not entrenched in his ways, and like so many filmmakers before him, it's when he stretches outside of his comfort zone that he becomes truly interesting. And by virtually any standard, "Hotel Chevalier" is his most original film ever (which basically means that it's ripping off Rohmer instead of Godard and Truffaut; I wonder if it's possible to make a movie about sex in Paris that doesn't rip off Rohmer?). At first it doesn't necessarily seem that way: there is as always the Andersonian fixation on exactly balanced compositions and claustrophobically specific color palettes, in this case yellow.

But dig in a bit, and it feels a little bit fresher: gone is the fussy production design of The Royal Tenenbaums and The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou, replaced by something that, by Anderson's standards, practically qualifies as minimalism. It reiterates something that has been easy to forget in the nine (!) years since Rushmore: Anderson's oh-so-formal compositions can be quite arresting when they're not aimed at obvious sets. Paris is a gorgeous city, but it's not often for it to have the geometric elegance that we see in the last few shots of Hotel Chevalier

And of course, there's the hatefucking.

Sex has been banished from the Wes Anderson universe 'til now, and for that matter, so has actual anger. Both are present - and how! - in this film, representing a new level of adult maturity that hasn't been in any of the director's frankly childlike films before. I think a large part of that can be credited to Natalie Portman: her acting style doesn't really fit in with the refined alienation that Anderson has brought in actors from Owen Wilson to Bill Murray to Anjelica Huston. Portman is much too physical and "present," if I can be a bit vague, to operate on that level of abstraction, and so much the better for her: she is an adult, come like an invading force into Anderson's hermetic world, and bringing with her emotional rawness that he has never ever touched upon before.

The film is a bit harsh, actually, and anti-romantic in a way that most American filmmakers don't even realise exists. That it has been filmed in the director's unmistakable idiom is jarring, but jarring in a way that shakes the staleness out of that style, and reminds us of what made it interesting in the first place: the way that it traps characters into formulaic modes of behavior that they cannot escape no matter how much they know that they are making terrible mistakes.

Anyway, don't listen to me. Just go watch the thing.

Categories: love stories, movies for pretentious people, quirkycore, wes anderson