No law at all in Macau

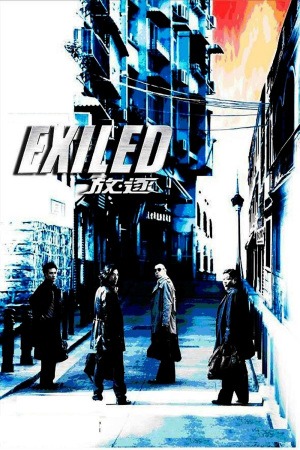

On 20 December, 1999, sovereignty of the Portuguese city-state colony of Macau was transferred to the People's Republic of China. At that time, Macau was a sort of semi-lawless frontier region, and it was for this reason that it makes the ideal setting for Hong Kong director Johnny To and screenwriters Szeto Kam-Yuen and Yip Tin-Shing to set their gauzy Western gangster picture Exiled.

Less a movie than a phantasmagorical dream synthesised from Sergio Leone and Sam Peckinpah, the story here, such as it can be pinned down, centers on Wo (Nick Cheung), a former gangster who has returned to settle down with a new wife (Josie Ho) and baby, against the explicit orders of his former leader, Boss Fay (Simon Yam). Fay sends a team of hitmen composed of Wo's former friends, led by the dour Blaze (Anthony Wong), to kill the man, but their friendship quickly rekindles, and the newly reformed gang elects to spend the waning days of Portuguese rule scrabbling for whatever bounties they can find before the frontier is shut down by the iron fist of Chinese authority.

Of course, it's all very easy and obvious when it's set down neat like that, but as Exiled unreels it feels much more impressionistic than narrative. The world of the film is decrepit and anarchic, especially as embodied by two cops who drift in and out of the plot at random, and constantly refuse to involve themselves in the conspicuously illegal goings-on in front of them, counting down the minutes and hours until the handover is complete and they are no longer responsible. It's unmistakably the territory of the American West, and the romance of Westerns from The Searchers to Deadwood, where morality is an inconvenient luxury and nothing is so hateful to the men of the frontier as the overhanging threat of civilisation, of The Government coming in to impose order on the power-mongers building private kingdoms in the wild.

And while all that is true, this is also a Hong Kong crime film, and as such there are many action sequences, and they are oh-so-loud and oh-so-violent; yet they are themselves derived not from the opera of chaos aesthetic of that country's most famous son John Woo, but from the late-'60s neo-Westerns. The film's opening, in which the team of assassins comes to Wo's apartment, is particularly reminiscent of Leone's Once Upon a Time in the West: there is even a slowly simmering pot that calls to mind the earlier movie's extensive use of water noises to build tension in its classic opening scene. To builds tension in much the same way that Leone did in that and other films: men with guns, as still as statues, minutes that can hardly be counted ticking by as nobody makes the first move. Then there is an explosion of violence and noise, lasting for but a moment.

Exiled never recaptures the raw, agonizing tension of its opening twenty minutes, but that's almost to its benefit: for it's after the first gunfight, when Wo and his friends reunite, that the film stops being a simple remix of Western style and becomes something much hazier and more fluid. It's not just that the plot becomes increasingly ephemeral - though it certainly does, at that - but that the actions represented become increasingly less mechanic and more, for want of a better word, poetic. The gang turns on Boss Fay and storms their way to the coast and back, and the action sequences that take place are largely exercises in...not even "style," which I was going to say, but more like mood and tone. There are many Peckinpah-like explosions of red mist in Peckinpah-like slow motion, but this lack the brutality of Peckinpah's violence (in films both Western and not). It's rather like watching an abstract ballet.

Part of this mood, I suppose, is the look of the cinematography by Cheng Siu-Keung. The movie is not very sharp, and not very colorful, and really the only way to describe it is to say that it looks something like a faded photograph. I have a feeling that cheap film stock was part of this, but the effect is both uncanny and mesmerising, separating us from the film in the manner of a poorly remembered dream. That's the second time I felt compelled to describe the film using the word "dream." Surely that means something. Other than my lazy vocabulary.

Some films, I think, are better experienced than thought about, and this is what I find true about Exiled. It has a feeling to it, instead of being concrete. There is nothing wrong with that, of course; it is the privilege art to engage the emotions by short-circuiting the brain. But bending my brain upon the film as best I can, here is what I believe: this is a film about times past encroaching upon in its narrative (Wo and his friends before his exile), in its setting (a historical event in Macau's history being revived for a new film), and in its style (the decades-old spaghetti Westerns). In life, we call such encroachment "memory," and Exiled is a visual representation of remembering. But it is also a film about past times that were better left in the past, brought to the present because that is the way of a blood tragedy. No memory is harder to bury than the memory of violence. This is why the return of all these past times is welcomed in explosions of blood - blood begets blood, and the unresolved traumas of the past become the traumas of today.

This is a vague review, but Exiled is a vague movie, vague in the best possible way. It is a film of impressions and sensations. It is a poem in cinematic form.

8/10

Less a movie than a phantasmagorical dream synthesised from Sergio Leone and Sam Peckinpah, the story here, such as it can be pinned down, centers on Wo (Nick Cheung), a former gangster who has returned to settle down with a new wife (Josie Ho) and baby, against the explicit orders of his former leader, Boss Fay (Simon Yam). Fay sends a team of hitmen composed of Wo's former friends, led by the dour Blaze (Anthony Wong), to kill the man, but their friendship quickly rekindles, and the newly reformed gang elects to spend the waning days of Portuguese rule scrabbling for whatever bounties they can find before the frontier is shut down by the iron fist of Chinese authority.

Of course, it's all very easy and obvious when it's set down neat like that, but as Exiled unreels it feels much more impressionistic than narrative. The world of the film is decrepit and anarchic, especially as embodied by two cops who drift in and out of the plot at random, and constantly refuse to involve themselves in the conspicuously illegal goings-on in front of them, counting down the minutes and hours until the handover is complete and they are no longer responsible. It's unmistakably the territory of the American West, and the romance of Westerns from The Searchers to Deadwood, where morality is an inconvenient luxury and nothing is so hateful to the men of the frontier as the overhanging threat of civilisation, of The Government coming in to impose order on the power-mongers building private kingdoms in the wild.

And while all that is true, this is also a Hong Kong crime film, and as such there are many action sequences, and they are oh-so-loud and oh-so-violent; yet they are themselves derived not from the opera of chaos aesthetic of that country's most famous son John Woo, but from the late-'60s neo-Westerns. The film's opening, in which the team of assassins comes to Wo's apartment, is particularly reminiscent of Leone's Once Upon a Time in the West: there is even a slowly simmering pot that calls to mind the earlier movie's extensive use of water noises to build tension in its classic opening scene. To builds tension in much the same way that Leone did in that and other films: men with guns, as still as statues, minutes that can hardly be counted ticking by as nobody makes the first move. Then there is an explosion of violence and noise, lasting for but a moment.

Exiled never recaptures the raw, agonizing tension of its opening twenty minutes, but that's almost to its benefit: for it's after the first gunfight, when Wo and his friends reunite, that the film stops being a simple remix of Western style and becomes something much hazier and more fluid. It's not just that the plot becomes increasingly ephemeral - though it certainly does, at that - but that the actions represented become increasingly less mechanic and more, for want of a better word, poetic. The gang turns on Boss Fay and storms their way to the coast and back, and the action sequences that take place are largely exercises in...not even "style," which I was going to say, but more like mood and tone. There are many Peckinpah-like explosions of red mist in Peckinpah-like slow motion, but this lack the brutality of Peckinpah's violence (in films both Western and not). It's rather like watching an abstract ballet.

Part of this mood, I suppose, is the look of the cinematography by Cheng Siu-Keung. The movie is not very sharp, and not very colorful, and really the only way to describe it is to say that it looks something like a faded photograph. I have a feeling that cheap film stock was part of this, but the effect is both uncanny and mesmerising, separating us from the film in the manner of a poorly remembered dream. That's the second time I felt compelled to describe the film using the word "dream." Surely that means something. Other than my lazy vocabulary.

Some films, I think, are better experienced than thought about, and this is what I find true about Exiled. It has a feeling to it, instead of being concrete. There is nothing wrong with that, of course; it is the privilege art to engage the emotions by short-circuiting the brain. But bending my brain upon the film as best I can, here is what I believe: this is a film about times past encroaching upon in its narrative (Wo and his friends before his exile), in its setting (a historical event in Macau's history being revived for a new film), and in its style (the decades-old spaghetti Westerns). In life, we call such encroachment "memory," and Exiled is a visual representation of remembering. But it is also a film about past times that were better left in the past, brought to the present because that is the way of a blood tragedy. No memory is harder to bury than the memory of violence. This is why the return of all these past times is welcomed in explosions of blood - blood begets blood, and the unresolved traumas of the past become the traumas of today.

This is a vague review, but Exiled is a vague movie, vague in the best possible way. It is a film of impressions and sensations. It is a poem in cinematic form.

8/10

Categories: action, crime pictures, gangster pictures, hong kong cinema, westerns