The asshole's tale

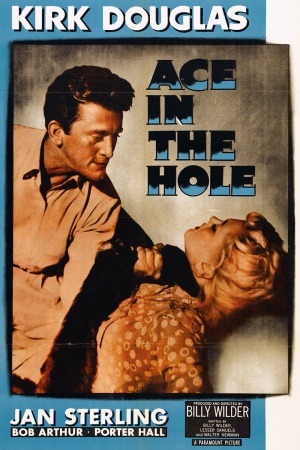

The natural human inclination is to assume that anything which is rare must also be of high quality, and this has led many of the few people who have been able to see Billy Wilder's long-lost Ace in the Hole from 1951 (released for the first time on any home video format last week) to declare it his greatest masterpiece. That's not a statement that I'm even a little bit comfortable with, but it is certainly is one of his masterpieces, and quite possibly the most Billy Wilder-ey of all his films. At any rate, it is a satiric dark comedy of shocking cynicism (check and double-check), neatly meeting the description one character in the film levels against the anti-hero: "I've met a lot of hard-boiled eggs in my time, but you - you're twenty minutes."

That anti-hero is Kirk Douglas in what may well be the role of his career: Chuck Tatum, a newspaper reporter with a well-honed sense of self-advancement, late of the East Coast and metropolitan Midwest ("I've been fired from papers in New York, Philadelphia, Chicago..." he brags), finding himself stuck for a year at a sleepy paper covering the sleepy non-news of Albuquerque, New Mexico. Then, purely by accident, he stumbles across a major human interest story: a man hunting for artifacts in a sacred burial site called "The Mountain of the Seven Vultures" has been trapped in a cave-in, and Tatum's journalistic spidey sense leads him to realize that this is the big story he's been waiting for; and thus does he turn the story into a national media circus, taking active steps to prolong the rescue effort, bed the man's wife, Lorraine (Jan Sterling).

Ace in the Hole looks like it should join Network in the annals of films about the news media that seemed like comic exaggerations in their time and now come across like documentaries; but that's not really right. For one thing, the concept is almost certainly based on the story of Kathy Fiscus, a young girl who was trapped in a mine just a couple of years prior to this film's release, and the subject during her incarceration of the most intensely focused media frenzy that any story had ever generated to that point. And besides, highly sensation news stories have always been with us: witness how many "Crimes of the Century" the last 100 years laid witness to.

I can't say that Kathy Fiscus was or wasn't a household name still in 1951, but she surely isn't now, and I suspect that Wilder and his co-writers Lesser Samuels and Walter Newman wanted their audience to assume that would be the case. The only thing surer than the preponderance of massive news stories, after all, is that whatever the next story down the pike, it will completely eradicate our recollection of the story that til now had been the center of our world. That subject was most family touched upon in the many variations of Chicago, the story of a murderer whose fame lasted about five seconds past her "not guilty" verdict: and in Ace in the Hole, it seems pretty clear from the desolate final act that only the principals will remember the trials of Leo Minosa for more than a day or two.

The important thing to bear in mind about Ace in the Hole is that it isn't really about the transience of news - it's about the rotten, corrupt soul of a man whose job is to make sure that there is always news. In short, a man who is directly responsible for the fast rise and equally fast disappearance of whatever major even he can scoop. Chuck Tatum is an American myth-maker, and his story is an indictment of the glee with which Americans absorb his myths, ghoulish and sensational as they are.

That's a story that has been told many time since, of course, but with the possible exceptions of Elia Kazan's A Face in the Crowd and the truly poisonous Sweet Smell of Success, I'm not certain that I've ever seen it told with the beautifully rancid cynicism that Wilder brings to bear here. Obviously, the director had a certain fame for taking the most pessimistic possible view of things, but that reaches a flowering in Ace in the Hole that I would hardly have imagined possible - Joe Gillis, the amoral opportunist of Sunset Blvd. from the year prior seems like a toothless dry run for Chuck Tatum's boundless misanthropy - and it's not surprising at all that audiences in the '50s didn't give it a chance. Frankly, even on the backside of the parade of ruthless anti-heroes of the 1970s, Tatum is a particularly unlikable protagonist. It's a little disconcerting to see an all-American like Kirk Douglas playing such a role, but it bears remembering that much of that actor's career, including a few truly terrific performances, was dedicated to fleshing out some really obnoxious assholes. And Douglas thrives here, as does Sterling, a leading lady who has been mostly forgotten nowadays; it's hard to say whether her unfamiliarity is what makes her performance so shattering, or if that's just what the actress was capable of. But she's an ice-cold bitch that matches Tatum note for note, in a glorious explosion of the most self-indulgent, vicious behavior that otherwise non-sociopathic humans are capable of.

Being a Billy Wilder film, there's plenty of choice dialogue, and being a particularly acidic Billy Wilder film, almost every line draws blood. Of course, that's part and parcel of the film noir, that speaking is replaced with launching bitter epigrams at the audience; and Ace in the Hole is surely a film noir, although one of the least typical examples of that genre that you will ever see. Befitting its desert setting, almost every scene that doesn't take place in the cave is bright and sunshiny; but the moral rot at the center, and the way that sexual politicking brings that rot out front and center, that's pure noir. Indeed, if we accept that noir was primarily about showcasing the moral instability of post-WWII America, they don't get much purer than this evisceration of our culture. The word "vulture" holds an important place in the film's discourse, always used in the name of the mountain, but it takes an unmistakably wider meaning. Tatum is a vulture of course, and so is Lorraine; but so are the teeming masses that write songs about Leo's entrapment, or set up a Ferris wheel outside the cave so that everybody who came to gawk at one man's suffering have plenty of distractions to keep themselves entertained while they wait for the man to escape or die. The film's re-release title, The Big Carnival, may not be as pungent as Ace in the Hole (the scene that reveals the specific meaning of that phrase is a punch in the crotch if ever I've seen one), but considering that it was meant to make the film sound more appealing, it comes off as particularly ironic. In America, watching the misfortunes of others is a sideshow pastime, and all of us who ever stopped our lives to track the minutiae of the Lindbergh kidnapping, or the O.J. Simpson trial, or the death of Anna Nicole Smith, are just as much uncaring bastards as the Chuck Tatums who only care about those stories because they sell so damn well.

That anti-hero is Kirk Douglas in what may well be the role of his career: Chuck Tatum, a newspaper reporter with a well-honed sense of self-advancement, late of the East Coast and metropolitan Midwest ("I've been fired from papers in New York, Philadelphia, Chicago..." he brags), finding himself stuck for a year at a sleepy paper covering the sleepy non-news of Albuquerque, New Mexico. Then, purely by accident, he stumbles across a major human interest story: a man hunting for artifacts in a sacred burial site called "The Mountain of the Seven Vultures" has been trapped in a cave-in, and Tatum's journalistic spidey sense leads him to realize that this is the big story he's been waiting for; and thus does he turn the story into a national media circus, taking active steps to prolong the rescue effort, bed the man's wife, Lorraine (Jan Sterling).

Ace in the Hole looks like it should join Network in the annals of films about the news media that seemed like comic exaggerations in their time and now come across like documentaries; but that's not really right. For one thing, the concept is almost certainly based on the story of Kathy Fiscus, a young girl who was trapped in a mine just a couple of years prior to this film's release, and the subject during her incarceration of the most intensely focused media frenzy that any story had ever generated to that point. And besides, highly sensation news stories have always been with us: witness how many "Crimes of the Century" the last 100 years laid witness to.

I can't say that Kathy Fiscus was or wasn't a household name still in 1951, but she surely isn't now, and I suspect that Wilder and his co-writers Lesser Samuels and Walter Newman wanted their audience to assume that would be the case. The only thing surer than the preponderance of massive news stories, after all, is that whatever the next story down the pike, it will completely eradicate our recollection of the story that til now had been the center of our world. That subject was most family touched upon in the many variations of Chicago, the story of a murderer whose fame lasted about five seconds past her "not guilty" verdict: and in Ace in the Hole, it seems pretty clear from the desolate final act that only the principals will remember the trials of Leo Minosa for more than a day or two.

The important thing to bear in mind about Ace in the Hole is that it isn't really about the transience of news - it's about the rotten, corrupt soul of a man whose job is to make sure that there is always news. In short, a man who is directly responsible for the fast rise and equally fast disappearance of whatever major even he can scoop. Chuck Tatum is an American myth-maker, and his story is an indictment of the glee with which Americans absorb his myths, ghoulish and sensational as they are.

That's a story that has been told many time since, of course, but with the possible exceptions of Elia Kazan's A Face in the Crowd and the truly poisonous Sweet Smell of Success, I'm not certain that I've ever seen it told with the beautifully rancid cynicism that Wilder brings to bear here. Obviously, the director had a certain fame for taking the most pessimistic possible view of things, but that reaches a flowering in Ace in the Hole that I would hardly have imagined possible - Joe Gillis, the amoral opportunist of Sunset Blvd. from the year prior seems like a toothless dry run for Chuck Tatum's boundless misanthropy - and it's not surprising at all that audiences in the '50s didn't give it a chance. Frankly, even on the backside of the parade of ruthless anti-heroes of the 1970s, Tatum is a particularly unlikable protagonist. It's a little disconcerting to see an all-American like Kirk Douglas playing such a role, but it bears remembering that much of that actor's career, including a few truly terrific performances, was dedicated to fleshing out some really obnoxious assholes. And Douglas thrives here, as does Sterling, a leading lady who has been mostly forgotten nowadays; it's hard to say whether her unfamiliarity is what makes her performance so shattering, or if that's just what the actress was capable of. But she's an ice-cold bitch that matches Tatum note for note, in a glorious explosion of the most self-indulgent, vicious behavior that otherwise non-sociopathic humans are capable of.

Being a Billy Wilder film, there's plenty of choice dialogue, and being a particularly acidic Billy Wilder film, almost every line draws blood. Of course, that's part and parcel of the film noir, that speaking is replaced with launching bitter epigrams at the audience; and Ace in the Hole is surely a film noir, although one of the least typical examples of that genre that you will ever see. Befitting its desert setting, almost every scene that doesn't take place in the cave is bright and sunshiny; but the moral rot at the center, and the way that sexual politicking brings that rot out front and center, that's pure noir. Indeed, if we accept that noir was primarily about showcasing the moral instability of post-WWII America, they don't get much purer than this evisceration of our culture. The word "vulture" holds an important place in the film's discourse, always used in the name of the mountain, but it takes an unmistakably wider meaning. Tatum is a vulture of course, and so is Lorraine; but so are the teeming masses that write songs about Leo's entrapment, or set up a Ferris wheel outside the cave so that everybody who came to gawk at one man's suffering have plenty of distractions to keep themselves entertained while they wait for the man to escape or die. The film's re-release title, The Big Carnival, may not be as pungent as Ace in the Hole (the scene that reveals the specific meaning of that phrase is a punch in the crotch if ever I've seen one), but considering that it was meant to make the film sound more appealing, it comes off as particularly ironic. In America, watching the misfortunes of others is a sideshow pastime, and all of us who ever stopped our lives to track the minutiae of the Lindbergh kidnapping, or the O.J. Simpson trial, or the death of Anna Nicole Smith, are just as much uncaring bastards as the Chuck Tatums who only care about those stories because they sell so damn well.