An old man's thoughts on youth

A little while ago, I briefly touched upon the three great Japanese master filmmakers of the mid-twentieth century. At the time, my goal was to provide some small context for the oldest, most prolific, and now the most obscure of the three, Mizoguchi Kenji; now, let me turn to the second, both in age and in number of films: Ozu Yasujiro.

It's probably not an exaggeration to suggest that Ozu is currently enjoying his period of greatest popularity in the West: although this popularity is based on an extremely small subset of his films, primarily Tokyo Story and Late Spring. The lucky among us have seen I Was Born, But... and therefore have some sense, not suggested by the first two, that the director was capable of making light movies with a good sense of humor.

It's only because Tokyo Story holds such a dramatic place of importance in our modern appreciation of the man that it comes as a surprise how much of his career was given over to comedy: his career was born in the notorious "salaryman" genre (notorious only for how poorly it translates to non-Japanese culture; also, for a very small number of cinephiles, because of how many Japanese sci-fi features were ruined due to their awful salaryman b-plots), those genial satires of white class life as traditional Japanese mores gave way to the hectic pace of Western industrialism. It may or may not qualify as a surprise that after his early post-war run of masterpieces that effectively carved in stone what we now think of as the "Ozu Style," the director returned to light social satire, not entirely like the salaryman films, but also not entirely different. It seems to me that we can probably think of his late run of films as combining the weighty domestic tragedy of Tokyo Story and its fellows with the genial humor of a salaryman film, and hence we arrive at the paradoxically light and serious Equinox Flower, Good Morning, or The End of Summer.

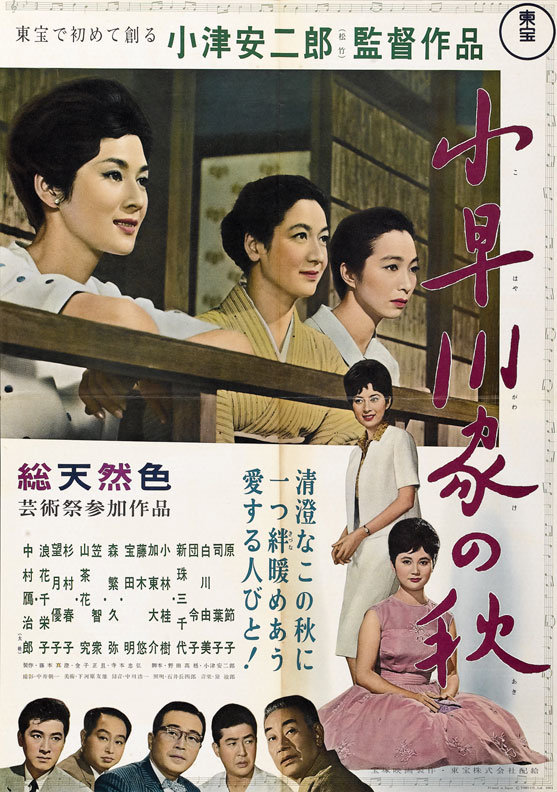

The End of Summer - or Early Autumn, or best of all, Autumn of the Kohayagawa Family - was the director's second to last film, and its simple story bears the instantly recognizable marks of an Ozu narrative: Kohayagawa Manbei (Nakamura Ganjiro) is an old widower, the owner of a tiny sake company, and the father of three daughters: Akiko (Hara Setsuko), the widowed eldest; Fumiko (Aratama Michiyo), married to Hisao (Kobayashi Keiju); and Noriko (Tsukasa Yôko), the youngest, still single. Everyone is much concerned with finding Noriko a husband, a touch less concerned with the same goal for Akiko, and as they're all dealing with various dramas in that vein, Manbei quietly resumes an affair with his old mistress, Tsune (Naniwa Chieko).

Throughout his career, Ozu was much concerned with the generational struggles of Japanese culture, particularly as the tension between the traditionalist elders clashed with their Westernized children, but in the final run of films of his life, he grew more and more to sympathise overtly with the younger generation and the new face of his country. In The End of Summer, this idea reaches a sort of peak: for not only does Ozu frame the Kohayagawa daughters as the protagonists simply from their presence and point-of-view, he constantly links their father to immaturity childishness: Manbei is frequently seen in the company of his young grandson, whom he seems to relate to more successfully than to any of his adult children, and he indulges in his love affair with the entitled attitude of a lovestruck teenager, right down to the ways in which he has to sneak around to see his lover. Which is not to say that Manbei is a dolt or an idiot; he is treated entirely sympathetically. It's just that his time has passed, and at the time the film has begun, it is already on the shoulder of the daughters to carry the respect of the Kohayagawa name. It is difficult to know what this meant to the 57-year-old director, two years away from his death and making his penultimate film; but it is impossible to think that it meant nothing at all.

It seems to me that I called this a light comedy, didn't I? And so it is. Considering how implicitly the film is about his own increasing irrelevance and approaching death, Ozu approached the matter of The End of Summer with good humor and high spirits. The early passages of the story are all cheerful and familial; it is only towards the end as death becomes a meaningful component of the story (Manbei suffers a non-fatal heart attack a bit past the half-way point) that the humor slows down and stops, and is replaced by the fear of loss. It's tempting to suggest that the arc of the film follows the arc of Ozu's career (from social comedies to family dramas) or really the arc of life itself (when we are young, we are playful, when we are middle-aged we are serious, and perhaps when we are very old, we are playful again).

This isn't just carried out in the story, but in the fabric of the filmmaking itself. Perversely, while Ozu's style is one of the most distinctive and important in the cinema, and while there are very few directors historically who have been better able to tell complete stories using just the simplest elements of visual composition, it is nearly impossible to explain how that style works without lapsing into repetition. For Ozu's style is nearly unchanging from film to film, and the elements of that style and how they work are well-described in too many places for me to think of imagining that I can bring something new to that conversation.

What I would like to argue, specifically in the context of The End of Summer and its generally good cheer, is the important difference between Ozu's color films and his black-and-white films: his color films are more fun to look at. I don't mean, for God's sake, that Tokyo Story or Early Summer aren't visually breathtaking movies. Rather, I mean that in those films, the use of composition and frame, of light and shadows, of movement, are all extremely specific and significant. In his color films, by contrast, while the composition and movement are all still very important, his use of colorful objects seems almost...arbitrary? I don't know what else to call it. It's using color just for the fun of it, not because there is any meaning to the color but because it is a delight to the eye. I find myself thinking of a shot in The End of Summer of a hallway, with men talking, all browns and blacks and greys, and then there is one bright blue lantern hanging just a bit above and to the right of center. It has nothing to do with the conversation being had, nor with the meaning of the film; but it is a playful thing to see, and that, I believe, is an incredibly important matter of tone. These last color films of Ozu are gentle and forgiving, and that is why they have visual elements that exist solely to appeal to the eye.

Late in the film, the two single daughters talk between themselves about the need to follow what society and family demand, as opposed to living according to their own happiness. Even in the face of death and doom, they maintain an upbeat certainty that the first thing is to be happy, and the rest will follow, and Ozu is glad to allow them their private happiness. The last shot of the film is a visual reminder of mortality straight out of Bergman, and it is clear that we are meant to regard this film as an elegy for the dying generation, but somehow it is not a sad elegy; instead, it takes comfort in the knowledge that no generation will ever be final, and that humanity goes on far beyond the facts of social change or one old man's life, be that man Kohayagawa Manbei or Ozu Yasujiro.

It's probably not an exaggeration to suggest that Ozu is currently enjoying his period of greatest popularity in the West: although this popularity is based on an extremely small subset of his films, primarily Tokyo Story and Late Spring. The lucky among us have seen I Was Born, But... and therefore have some sense, not suggested by the first two, that the director was capable of making light movies with a good sense of humor.

It's only because Tokyo Story holds such a dramatic place of importance in our modern appreciation of the man that it comes as a surprise how much of his career was given over to comedy: his career was born in the notorious "salaryman" genre (notorious only for how poorly it translates to non-Japanese culture; also, for a very small number of cinephiles, because of how many Japanese sci-fi features were ruined due to their awful salaryman b-plots), those genial satires of white class life as traditional Japanese mores gave way to the hectic pace of Western industrialism. It may or may not qualify as a surprise that after his early post-war run of masterpieces that effectively carved in stone what we now think of as the "Ozu Style," the director returned to light social satire, not entirely like the salaryman films, but also not entirely different. It seems to me that we can probably think of his late run of films as combining the weighty domestic tragedy of Tokyo Story and its fellows with the genial humor of a salaryman film, and hence we arrive at the paradoxically light and serious Equinox Flower, Good Morning, or The End of Summer.

The End of Summer - or Early Autumn, or best of all, Autumn of the Kohayagawa Family - was the director's second to last film, and its simple story bears the instantly recognizable marks of an Ozu narrative: Kohayagawa Manbei (Nakamura Ganjiro) is an old widower, the owner of a tiny sake company, and the father of three daughters: Akiko (Hara Setsuko), the widowed eldest; Fumiko (Aratama Michiyo), married to Hisao (Kobayashi Keiju); and Noriko (Tsukasa Yôko), the youngest, still single. Everyone is much concerned with finding Noriko a husband, a touch less concerned with the same goal for Akiko, and as they're all dealing with various dramas in that vein, Manbei quietly resumes an affair with his old mistress, Tsune (Naniwa Chieko).

Throughout his career, Ozu was much concerned with the generational struggles of Japanese culture, particularly as the tension between the traditionalist elders clashed with their Westernized children, but in the final run of films of his life, he grew more and more to sympathise overtly with the younger generation and the new face of his country. In The End of Summer, this idea reaches a sort of peak: for not only does Ozu frame the Kohayagawa daughters as the protagonists simply from their presence and point-of-view, he constantly links their father to immaturity childishness: Manbei is frequently seen in the company of his young grandson, whom he seems to relate to more successfully than to any of his adult children, and he indulges in his love affair with the entitled attitude of a lovestruck teenager, right down to the ways in which he has to sneak around to see his lover. Which is not to say that Manbei is a dolt or an idiot; he is treated entirely sympathetically. It's just that his time has passed, and at the time the film has begun, it is already on the shoulder of the daughters to carry the respect of the Kohayagawa name. It is difficult to know what this meant to the 57-year-old director, two years away from his death and making his penultimate film; but it is impossible to think that it meant nothing at all.

It seems to me that I called this a light comedy, didn't I? And so it is. Considering how implicitly the film is about his own increasing irrelevance and approaching death, Ozu approached the matter of The End of Summer with good humor and high spirits. The early passages of the story are all cheerful and familial; it is only towards the end as death becomes a meaningful component of the story (Manbei suffers a non-fatal heart attack a bit past the half-way point) that the humor slows down and stops, and is replaced by the fear of loss. It's tempting to suggest that the arc of the film follows the arc of Ozu's career (from social comedies to family dramas) or really the arc of life itself (when we are young, we are playful, when we are middle-aged we are serious, and perhaps when we are very old, we are playful again).

This isn't just carried out in the story, but in the fabric of the filmmaking itself. Perversely, while Ozu's style is one of the most distinctive and important in the cinema, and while there are very few directors historically who have been better able to tell complete stories using just the simplest elements of visual composition, it is nearly impossible to explain how that style works without lapsing into repetition. For Ozu's style is nearly unchanging from film to film, and the elements of that style and how they work are well-described in too many places for me to think of imagining that I can bring something new to that conversation.

What I would like to argue, specifically in the context of The End of Summer and its generally good cheer, is the important difference between Ozu's color films and his black-and-white films: his color films are more fun to look at. I don't mean, for God's sake, that Tokyo Story or Early Summer aren't visually breathtaking movies. Rather, I mean that in those films, the use of composition and frame, of light and shadows, of movement, are all extremely specific and significant. In his color films, by contrast, while the composition and movement are all still very important, his use of colorful objects seems almost...arbitrary? I don't know what else to call it. It's using color just for the fun of it, not because there is any meaning to the color but because it is a delight to the eye. I find myself thinking of a shot in The End of Summer of a hallway, with men talking, all browns and blacks and greys, and then there is one bright blue lantern hanging just a bit above and to the right of center. It has nothing to do with the conversation being had, nor with the meaning of the film; but it is a playful thing to see, and that, I believe, is an incredibly important matter of tone. These last color films of Ozu are gentle and forgiving, and that is why they have visual elements that exist solely to appeal to the eye.

Late in the film, the two single daughters talk between themselves about the need to follow what society and family demand, as opposed to living according to their own happiness. Even in the face of death and doom, they maintain an upbeat certainty that the first thing is to be happy, and the rest will follow, and Ozu is glad to allow them their private happiness. The last shot of the film is a visual reminder of mortality straight out of Bergman, and it is clear that we are meant to regard this film as an elegy for the dying generation, but somehow it is not a sad elegy; instead, it takes comfort in the knowledge that no generation will ever be final, and that humanity goes on far beyond the facts of social change or one old man's life, be that man Kohayagawa Manbei or Ozu Yasujiro.

Categories: domestic dramas, japanese cinema, sunday classic movies