Brother John and Sister Kate

Ah, the centenary! Such a sacral observance for beings such as we, that are hard-wired to think in tens. And this month witnesses two that are not so important in the great scheme of things, but mean quite a lot to me: Katharine Hepburn's 100th on May 12, and John Wayne's on May 26.

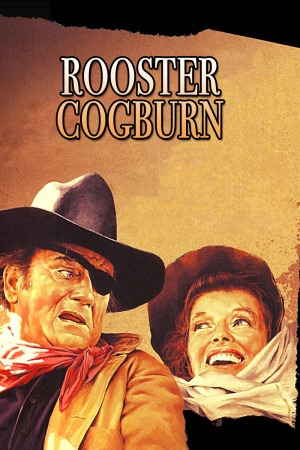

Being me, I couldn't let those dates go by unnoticed, and it seemed the most natural thing in the world to use this opportunity to watch the one and only film that those ever made together: Rooster Cogburn, the continuing adventures of the drunken asshole lawman that brought Wayne his first and only Oscar in 1969's True Grit.

As films go, Rooster Cogburn is maybe not the most memorable thing in the world, which is not to say that it is without charm. It's just very slight. Stuart Millar, the director, was by trade a producer (although curiously, not of this particular film), and it really does show that he doesn't have much clue what he's doing. And screenwriter Martha Hyer, a Western character actress working under the pseudonym "Martin Julien," never wrote another film before or since. Given these two facts it's none to surprising that the story kind of ambles around and never amounts to much of anything. It's also shockingly derivative, although 30 years on its that very quality that tends to make the plot more interesting.

The story opens in a very familiar place: Marshal "Rooster" Cogburn has just ended the reign of terror of a small gang by the expedient of killing them all. The local magistrate, Judge Parker (prolific character actor John McIntire) can't stand these rough 'n' tumble marshals who take the law into their own hands, and so he strips Cogburn of his badge, sending him off to be belligerent and drunk in exile. In other words, Rooster Cogburn falls into the tradition of "cop that's too tough for the system" movies, that has become unspeakably hoary by now, but in 1975 was still...not "fresh," but not tempered by decades of overuse. At any rate, it fascinates me to no end that John Wayne found himself, at the end of his career, playing the Harry Callahan of the Indian Territory.

Of course, this being that kind of movie, Cogburn is given the chance to redeem himself if he can apprehend a particularly vicious criminal without recourse to lethal violence, and in no time at all, he's on the trail of Breed (Anthony Zerbe), a villain who has just laid bloody waste to a school just inside the Territory, killing several locals and the placid white preacher who taught there. The only survivors are Wolf (Richard Romancito), a teenage boy, and Eula Goodnight (Hepburn), the spinster daughter of the preacher.

Cogburn and Miss Goodnight* join up, against the lawman's will, to track Breed's gang, and at that point we stop caring about the plot entirely, but it goes a little bit something like this: Cogburn is rough and crude and drunk, Goodnight is prim and religious, they spar as they adventure, but slowly come to some sort of affection for each other. It is, in other words, a precise rip-off of Hepburn's The African Queen, which is its own special weird metanarrative thing that I'll return to in a moment.

By the time we come to the fairly idiotic climax to the plot, it's more or less obvious that Rooster Cogburn isn't a conventionally successful Western (indeed, as a "film," the only really good thing about it is Harry Stradling's cinematography, with some really amazing compositions in the first twenty minutes or so). Instead, it's a strange postmodern commentary on the idea of movie star personae. Clearly I don't know if that was anyone's specific intent, nor do I know if the film was conceived before or after Kate Hepburn signed on. But the film as it stands is less of a conflict between Rooster and Eula, or Rooster/Eula against the outlaws, but between John Wayne and Katharine Hepburn's respective filmographies.

What is a John Wayne character? Gruff and masculine, a bit misogynist, good with a gun, sharp-tongued, strong personal moral code (of course, all of these things can be either positive or negative, depending upon the particular role). And what is a Katharine Hepburn character? Also sharp-tongued, but refined, old money, strong-willed, feminist, educated. Within the film itself, these differences are commented on, but they absolutely don't need to be.

No viewer is likely to come to Rooster Cogburn unaware of its two headliners, and so the film has the luxury of trading on our knowledge of the decades of films between them. I don't mean to say that it's a lazy film (certainly, both performers - Wayne especially - had starred in plenty of movies that traded 100% on the star's persona). Rather, I mean that it is a sort of controlled experiment in what happens when two completely incompatible movie stars occupy the same physical space without changing what makes them a star.

Such mash-ups have occurred throughout the history of cinema with typically unsuccessful results, but in 1975, Hepburn and Wayne weren't just popular actors, they were living legends. Their pairing would have been less of a stunt-casting commercial event and more of a battle between gods. Watching the two together works on the level of enjoying two great actors, of course, but it also works on the rarer and more intriguing level of what makes those actors great. Contrasting the two stars makes us unusually aware of the mechanical aspects of their respective personae, which is a needlessly confusing way of saying that putting Hepburn and Wayne against an alien romantic lead has the effect of isolating the actors, and allowing us to consider their characteristics more fully once they have been so isolated. Given our knowledge that the audience lacked in 1975, that the two stars would only make five more films between them, we now have the added thrill of considering these superstars-in-isolation as the culmination of lifetimes, and while for neither actor would this have been a great swan song, it is still the case that this deconstruction could only have been possible at the end of a career.

If all that makes it seem like the movie itself isn't so great, well, it's not. But it is a perfectly wonderful treat for fans of the two stars, and there's precious damn little reason for anyone to be a fan of neither Hepburn nor Wayne. In a way, it's something better than good: it's interesting, because it allows us to briefly recontextualize two exceedingly familiar faces, and think about why we like them specifically, rather than just mindlessly enjoying their familiarity.

Being me, I couldn't let those dates go by unnoticed, and it seemed the most natural thing in the world to use this opportunity to watch the one and only film that those ever made together: Rooster Cogburn, the continuing adventures of the drunken asshole lawman that brought Wayne his first and only Oscar in 1969's True Grit.

As films go, Rooster Cogburn is maybe not the most memorable thing in the world, which is not to say that it is without charm. It's just very slight. Stuart Millar, the director, was by trade a producer (although curiously, not of this particular film), and it really does show that he doesn't have much clue what he's doing. And screenwriter Martha Hyer, a Western character actress working under the pseudonym "Martin Julien," never wrote another film before or since. Given these two facts it's none to surprising that the story kind of ambles around and never amounts to much of anything. It's also shockingly derivative, although 30 years on its that very quality that tends to make the plot more interesting.

The story opens in a very familiar place: Marshal "Rooster" Cogburn has just ended the reign of terror of a small gang by the expedient of killing them all. The local magistrate, Judge Parker (prolific character actor John McIntire) can't stand these rough 'n' tumble marshals who take the law into their own hands, and so he strips Cogburn of his badge, sending him off to be belligerent and drunk in exile. In other words, Rooster Cogburn falls into the tradition of "cop that's too tough for the system" movies, that has become unspeakably hoary by now, but in 1975 was still...not "fresh," but not tempered by decades of overuse. At any rate, it fascinates me to no end that John Wayne found himself, at the end of his career, playing the Harry Callahan of the Indian Territory.

Of course, this being that kind of movie, Cogburn is given the chance to redeem himself if he can apprehend a particularly vicious criminal without recourse to lethal violence, and in no time at all, he's on the trail of Breed (Anthony Zerbe), a villain who has just laid bloody waste to a school just inside the Territory, killing several locals and the placid white preacher who taught there. The only survivors are Wolf (Richard Romancito), a teenage boy, and Eula Goodnight (Hepburn), the spinster daughter of the preacher.

Cogburn and Miss Goodnight* join up, against the lawman's will, to track Breed's gang, and at that point we stop caring about the plot entirely, but it goes a little bit something like this: Cogburn is rough and crude and drunk, Goodnight is prim and religious, they spar as they adventure, but slowly come to some sort of affection for each other. It is, in other words, a precise rip-off of Hepburn's The African Queen, which is its own special weird metanarrative thing that I'll return to in a moment.

By the time we come to the fairly idiotic climax to the plot, it's more or less obvious that Rooster Cogburn isn't a conventionally successful Western (indeed, as a "film," the only really good thing about it is Harry Stradling's cinematography, with some really amazing compositions in the first twenty minutes or so). Instead, it's a strange postmodern commentary on the idea of movie star personae. Clearly I don't know if that was anyone's specific intent, nor do I know if the film was conceived before or after Kate Hepburn signed on. But the film as it stands is less of a conflict between Rooster and Eula, or Rooster/Eula against the outlaws, but between John Wayne and Katharine Hepburn's respective filmographies.

What is a John Wayne character? Gruff and masculine, a bit misogynist, good with a gun, sharp-tongued, strong personal moral code (of course, all of these things can be either positive or negative, depending upon the particular role). And what is a Katharine Hepburn character? Also sharp-tongued, but refined, old money, strong-willed, feminist, educated. Within the film itself, these differences are commented on, but they absolutely don't need to be.

No viewer is likely to come to Rooster Cogburn unaware of its two headliners, and so the film has the luxury of trading on our knowledge of the decades of films between them. I don't mean to say that it's a lazy film (certainly, both performers - Wayne especially - had starred in plenty of movies that traded 100% on the star's persona). Rather, I mean that it is a sort of controlled experiment in what happens when two completely incompatible movie stars occupy the same physical space without changing what makes them a star.

Such mash-ups have occurred throughout the history of cinema with typically unsuccessful results, but in 1975, Hepburn and Wayne weren't just popular actors, they were living legends. Their pairing would have been less of a stunt-casting commercial event and more of a battle between gods. Watching the two together works on the level of enjoying two great actors, of course, but it also works on the rarer and more intriguing level of what makes those actors great. Contrasting the two stars makes us unusually aware of the mechanical aspects of their respective personae, which is a needlessly confusing way of saying that putting Hepburn and Wayne against an alien romantic lead has the effect of isolating the actors, and allowing us to consider their characteristics more fully once they have been so isolated. Given our knowledge that the audience lacked in 1975, that the two stars would only make five more films between them, we now have the added thrill of considering these superstars-in-isolation as the culmination of lifetimes, and while for neither actor would this have been a great swan song, it is still the case that this deconstruction could only have been possible at the end of a career.

If all that makes it seem like the movie itself isn't so great, well, it's not. But it is a perfectly wonderful treat for fans of the two stars, and there's precious damn little reason for anyone to be a fan of neither Hepburn nor Wayne. In a way, it's something better than good: it's interesting, because it allows us to briefly recontextualize two exceedingly familiar faces, and think about why we like them specifically, rather than just mindlessly enjoying their familiarity.

Categories: sunday classic movies, westerns