The long and winding road

From the files of: "Hey, I've owned that DVD for more than a year, I should really think about watching it!"

And now, the Golden Delicious apple.

Come back with me to the late 1940s. World War II is over and America celebrates by inventing Suburbia, as both place and attitude. The ideal of this new America is the neat house with the big yard with two or three rosy-cheeked children scampering as Mom cooks and Dad comes home from his white collar job. It is false world, of course. It is a world of marketing. It is a world in which things have frilly, wonderful names, because the outer appearance is all. If something looks and sounds divine, then it has value.

In other words, the Golden Delicious apple.

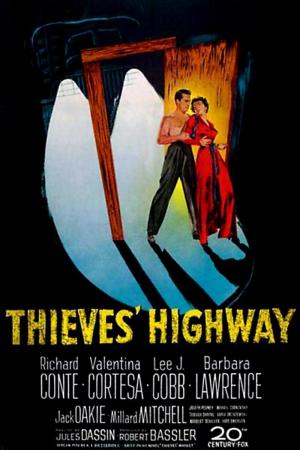

The Golden Delicious hangs over every frame of Jules Dassin's 1949 film noir Thieves' Highway like an albatross. This is the story of Nick Garcos (Richard Conte), who returns home to Fresno, California after a lengthy stint in the postwar armed forces, only to find that his father, a former fruit trucker, has been cheated out of his money by a devious San Francisco produce dealer named Mike Figlia (Lee J. Cobb), and crippled in a driving accident. Seeking revenge, Nick joins with a veteran trucker who has an inside track on the season's first crop of apples, which the two men agree will be tempting bait with which to trap Figlia. Those apples, of course, are Golden Delicious.

Although his career began as a journeyman director making romantic comedies and period pieces (and period comedies), Dassin's modern reputation rests upon the run of films noirs he made starting in 1947 with Brute Force, running into the first several years of his McCarthy-era exile in Europe,* so it is no surprise that Thieves' Highway is a dark film; but the extent to which it is dark is surprising even in the context of the surpassing bleak postwar noirs. Out of 94 minutes, perhaps 20 take place during the day. The rest is set in the blackest night, whether on the long dark highway between Fresno and San Francisco, or on the busy streets of the SF markets, or in the cheap lighting of a whore's flat. I think the word for such style is "unremitting."

Thieves' Highway is not the nastiest, darkest American film I've seen from that generation, mind you. If anything, it's full of biting sarcasm, much moreso than any other film I can name from that early in the American noir cycle. Then again, sarcasm is not "funny" here so much as it is nihilistic, and so even the film's attempts at comic relief in the form of a team of rival truckers played by Jack Oakie and Joseph Pevney turn out to be rather more curdled and acidic than humorous.

Why so exceptionally dark? The answer comes in the form of an extraordinary bit of dialogue between Nick and the prostitute Rica, embodied brilliantly by Valentina Cortese:

From the get-go, Dassin pushes the subtle mockery of suburban life, even from the opening establishing shot of Fresno, which emphasize its isolation and its smallness. Indeed, Thieves' Highway is full of shots that minimize the scale of things. The genre is, if anything, noted for the ways in which camera angles are used to intensify physical presence, but Dassin shoots nearly every scene from straight ahead, diminishing and flattening the players. The visual tension comes instead from the harsh contrasts that dominate the film after its opening beats, white figures against inky blackness. It turns this from a story of men against men (which it is) to a story of men against the world (which it also is) - in other words, a social message film noir.

But as I mentioned, I maintain that the film's primary tension is between the brand new laconic middle class and the miserable souls who made sure they got their damn apples. This is clearest in a comparison of the film's two women: Polly (Barbara Lawrence), the girl who's been waiting at home for Nick's return, and Rica, the exotic European femme who embodies all of the sexual potency that the postwar suburban milieu was specifically geared towards repressing. Polly is a reedy pill; she has no use for Nick other than as a money-making protector, and her characterization is thin and clichéd. But Rica! Valentina Cortese was just one of those actresses who smoldered at her very core, and she turns Rica into one of the great sexually aggressive women of the 1940s cinema. She is vital and alive in all the ways that Polly is not. In the film's single most memorable moment, she scratches out a tic-tac-toe board on his naked pectorals with her sharp fingernails, and they play a quick game. How this got past the censors, I'll never know, but it works beyond imagining to establish instantly their perfect chemistry. And Rica, who is constantly verbally tied to the street and not just as "streetwalker," is the embodiment of the urban poor. She is real in a way that the suburban princess Polly cannot even begin to imagine.

This core premise that America finds comfort on the suffering of the anonymous masses finds a more pervasive and subtler embodiment in Nick himself, and his delivery truck of all things. Nick, of course, was in the armed forces, during and after the war; yet he's given no respect for it. And his truck is a decommisioned army supply vehicle that hasn't even been repainted. The sight of an apple delivery truck with the US Army star painted on its doors is mildly comic at first, but every time we see it, it's a little bit less so, until we finally understand the point, that this is what the war veteran has been reduced to in a postwar America - even more tragically in this age because we know what Dassin didn't that WWII was actually the legitimate last war in which Americans fought for our own safety. The apple-eaters don't care about the GI driving the army truck. They just want the Golden Delicious. Sacrifice is for other people.

It's not a movie if there isn't some terrible flaw that gnaws at the whole edifice, and Thieves' Highway obliges with one of the cheapest cop-out endings in any film noir I can immediately name. We must not blame Dassin and Bezzerides, who both strongly objected, but Darryl Zanuck and the Fox machine, who crudely shoved a pair of final scenes that serves to endorse the status quo and flatten the film's pungent sexual energy. Wherever the blame lies, these scenes don't work. At all. And they undo much of the film's effectiveness to that point.

Even so, there's the rest of the 94 minutes to consider, and Lord above is there ever a lot to consider there. I've looked at only one thread of the film, and it's a good thread, but this is straight up a brilliant noir, with one of the most hard-boiled heroes in that genre to that point, and I tend to wonder if it might be essentially inexhaustible. This is American filmmaking at its finest.

And now, the Golden Delicious apple.

Come back with me to the late 1940s. World War II is over and America celebrates by inventing Suburbia, as both place and attitude. The ideal of this new America is the neat house with the big yard with two or three rosy-cheeked children scampering as Mom cooks and Dad comes home from his white collar job. It is false world, of course. It is a world of marketing. It is a world in which things have frilly, wonderful names, because the outer appearance is all. If something looks and sounds divine, then it has value.

In other words, the Golden Delicious apple.

The Golden Delicious hangs over every frame of Jules Dassin's 1949 film noir Thieves' Highway like an albatross. This is the story of Nick Garcos (Richard Conte), who returns home to Fresno, California after a lengthy stint in the postwar armed forces, only to find that his father, a former fruit trucker, has been cheated out of his money by a devious San Francisco produce dealer named Mike Figlia (Lee J. Cobb), and crippled in a driving accident. Seeking revenge, Nick joins with a veteran trucker who has an inside track on the season's first crop of apples, which the two men agree will be tempting bait with which to trap Figlia. Those apples, of course, are Golden Delicious.

Although his career began as a journeyman director making romantic comedies and period pieces (and period comedies), Dassin's modern reputation rests upon the run of films noirs he made starting in 1947 with Brute Force, running into the first several years of his McCarthy-era exile in Europe,* so it is no surprise that Thieves' Highway is a dark film; but the extent to which it is dark is surprising even in the context of the surpassing bleak postwar noirs. Out of 94 minutes, perhaps 20 take place during the day. The rest is set in the blackest night, whether on the long dark highway between Fresno and San Francisco, or on the busy streets of the SF markets, or in the cheap lighting of a whore's flat. I think the word for such style is "unremitting."

Thieves' Highway is not the nastiest, darkest American film I've seen from that generation, mind you. If anything, it's full of biting sarcasm, much moreso than any other film I can name from that early in the American noir cycle. Then again, sarcasm is not "funny" here so much as it is nihilistic, and so even the film's attempts at comic relief in the form of a team of rival truckers played by Jack Oakie and Joseph Pevney turn out to be rather more curdled and acidic than humorous.

Why so exceptionally dark? The answer comes in the form of an extraordinary bit of dialogue between Nick and the prostitute Rica, embodied brilliantly by Valentina Cortese:

NICK: Hey, do you like apples?To me this is the crux of the entire film: it is a savage attack on American comfort. To a certain degree, this speech is redundant, for by this point we've already seen all of the indignities that Nick describes, and if that wasn't enough to make us understand that this is some tough shit here, the constant repetition of "Golden Delicious" by every character in the film until the phrase is stripped of even the slightest romance. But the point the story that the speech occupies turns it into a sort of recapitulation, a reminder of where we've been.

RICA: Everybody likes apples, except doctors.

NICK: Do you know what it takes to get an apple so you can sink your beautiful teeth in it? You gotta stuff rags up tailpipes, farmers gotta get gypped, you jack up trucks with the back of your neck, universals conk out...

From the get-go, Dassin pushes the subtle mockery of suburban life, even from the opening establishing shot of Fresno, which emphasize its isolation and its smallness. Indeed, Thieves' Highway is full of shots that minimize the scale of things. The genre is, if anything, noted for the ways in which camera angles are used to intensify physical presence, but Dassin shoots nearly every scene from straight ahead, diminishing and flattening the players. The visual tension comes instead from the harsh contrasts that dominate the film after its opening beats, white figures against inky blackness. It turns this from a story of men against men (which it is) to a story of men against the world (which it also is) - in other words, a social message film noir.

But as I mentioned, I maintain that the film's primary tension is between the brand new laconic middle class and the miserable souls who made sure they got their damn apples. This is clearest in a comparison of the film's two women: Polly (Barbara Lawrence), the girl who's been waiting at home for Nick's return, and Rica, the exotic European femme who embodies all of the sexual potency that the postwar suburban milieu was specifically geared towards repressing. Polly is a reedy pill; she has no use for Nick other than as a money-making protector, and her characterization is thin and clichéd. But Rica! Valentina Cortese was just one of those actresses who smoldered at her very core, and she turns Rica into one of the great sexually aggressive women of the 1940s cinema. She is vital and alive in all the ways that Polly is not. In the film's single most memorable moment, she scratches out a tic-tac-toe board on his naked pectorals with her sharp fingernails, and they play a quick game. How this got past the censors, I'll never know, but it works beyond imagining to establish instantly their perfect chemistry. And Rica, who is constantly verbally tied to the street and not just as "streetwalker," is the embodiment of the urban poor. She is real in a way that the suburban princess Polly cannot even begin to imagine.

This core premise that America finds comfort on the suffering of the anonymous masses finds a more pervasive and subtler embodiment in Nick himself, and his delivery truck of all things. Nick, of course, was in the armed forces, during and after the war; yet he's given no respect for it. And his truck is a decommisioned army supply vehicle that hasn't even been repainted. The sight of an apple delivery truck with the US Army star painted on its doors is mildly comic at first, but every time we see it, it's a little bit less so, until we finally understand the point, that this is what the war veteran has been reduced to in a postwar America - even more tragically in this age because we know what Dassin didn't that WWII was actually the legitimate last war in which Americans fought for our own safety. The apple-eaters don't care about the GI driving the army truck. They just want the Golden Delicious. Sacrifice is for other people.

It's not a movie if there isn't some terrible flaw that gnaws at the whole edifice, and Thieves' Highway obliges with one of the cheapest cop-out endings in any film noir I can immediately name. We must not blame Dassin and Bezzerides, who both strongly objected, but Darryl Zanuck and the Fox machine, who crudely shoved a pair of final scenes that serves to endorse the status quo and flatten the film's pungent sexual energy. Wherever the blame lies, these scenes don't work. At all. And they undo much of the film's effectiveness to that point.

Even so, there's the rest of the 94 minutes to consider, and Lord above is there ever a lot to consider there. I've looked at only one thread of the film, and it's a good thread, but this is straight up a brilliant noir, with one of the most hard-boiled heroes in that genre to that point, and I tend to wonder if it might be essentially inexhaustible. This is American filmmaking at its finest.

Categories: action, film noir, post-war hollywood, sunday classic movies