Crazy Frenchies

The French New Wave remains, in my humble opinion, the most exciting and energetic of all film movements, because of the unmistakable joy that the directors involved had in deconstructing the mechanics of cinema. It is the most playful of all film schools; even its stories of death and betrayal and its vicious political satires are so alive with delight.

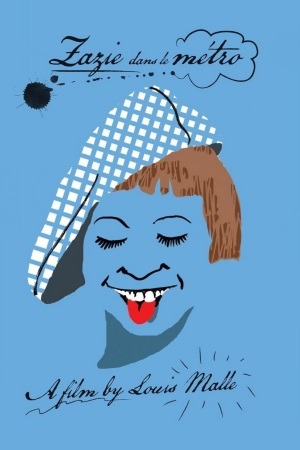

And for all that, I don't believe that I'm familiar with any New Wave film so full of that energy as Louis Malle's third feature, Zazie in the Metro. Part of that energy comes from the subject: the misadventures of a young girl set loose in Paris. And part of it comes from the film's rather unique status in the New Wave canon as being not just a comedic riff on a serious genre; in fact it is an outright comedy.

Here is the first thing that I learned about New Wave comedy: it is freakishly unhinged. In my life, I have been more than happy to call Truffaut's Shoot the Piano Player or Godard's A Woman is a Woman or Band of Outsiders "surreal" in the way that they break the rules of cinematic diegesis (that is, the realty of the narrative world, which is different from the reality of what is represented onscreen) beyond the basic experimentation that was a hallmark of the New Wave; but Zazie knocks them all away. It is not merely Surrealist, it leaves Surrealism behind on its merry trip into outright Absurdism, and while I watched the film I thought of neither Godard nor Truffaut, nor Buñuel, but Monty Python's Flying Circus and its aggressive abandonment of causality and even physics in the pursuit of the grotesque and ineffable.

Even that's not precisely right. The Pythons were largely content to embrace the moral and aesthetic anarchism of absurdity in the pursuit of humor, and while Zazie in the Metro has its fair share of slapstick and farce and potty jokes, much of the anarchism (even that same juvenile vaudeville) is considerably more dangerous than I am accustomed to. For example: reasonably early in the film, Zazie (Catherine Demongeot) find herself being pursued by a man of no permanent name (Vittorio Caprioli), who at this point seems to be a pedophile (nor is it ever demonstrated that he isn't a pedophile, but it falls into the background). He chases her through Paris in an extended setpiece that can only be called an homage to Tex Avery: not just in its manic speed, but in Zazie's ability to completely disregard physics, by being in multiple places at once, by being able to jump around in impossible ways, by being able to materialise cartoon bombs at will, and by the man's reaction to blowing up being to turn completely black except for his eyes and mustache. Set aside the fact that, moments before this scene began, Zazie was being menaced by a sex predator; the mere fact that a live-action film completely co-opts the vocabulary of a cartoon is shocking and somehow offensive to the mind, yet it is also deliriously funny.

"Delirium." Let us hold onto that word, savor it and consider it for the current subject. It refers to an anxious state of mind characterised by confusion and hallucination and incoherence, and all of these are perfectly correct adjectives to describe Zazie in the Metro.

Godard famously held that the aesthetics of a film should be a political argument, but he was never able to successfully demonstrate such a thing; late in the 1960s, he began grafting the vocabulary of the New Wave onto explicitly political screenplays, but there was no concomitant change in his style. Politics was always in his writing, not his directing. But even if he had succeeded in his quest, Malle would have already beaten him to the punch, for Zazie is a political argument to its very core. "Dangerous anarchy," I stated before, and I will repeat it: this is an anarchic film, not "anarchic" in the way that we playfully describe the Marx Brothers or screwball comedy or, yes, Monty Python; "anarchic" because it rips things apart and eliminates meaning, because it implicitly argues that the very idea of society is fascist. To be a human amongst humans is to live in a world of rules, and Zazie in the Metro proceeds to eliminate those rules not just in its plot, although it does so, but in its make-up. The cartoon homage is a good reference point for that, as animation in general and Tex Avery's chase films in particular have long been regarded as the ultimate in cinematic anarchy, where even the totalitarianism of physics is overthrown. That's not the only anarchy in the film, however, not by a long shot: there are constant, completely unmotivated continuity errors; the soundscape is violently loud and often unconnected to the imagery; characters refuse to act with any consistency or regard for the situations around them. Even the sets themselves refuse to be nailed down, as neatly demonstrated in a bar that is being constantly redecorated, including a phone that blows up in the middle of a conversation and continues to operate.

Of course, Godard was certainly no stranger to the idea that society is inherently fascist. It's just that the only way he knew to film that theme was to put heavy-handed dialogue in the mouth of a pop star wearing a Coca Cola shirt intercut with title cards that are bawdy anagrams of Proust quotes.* Not that I don't love Godard for that sort of thing, because of course I do and I always will, but he had to work for his politics. Malle's film embodies politics, seemingly without effort. It is the most political New Wave film I have ever seen, in fact, to such an unforgiving degree that it is somewhat uncomfortable to watch.

That the film is ameliorated whatsoever in this total discomfort, and returned to the realm of comedy, is because it is centered around an eleven-year-old girl. And if one were so inclined, it would be possible to read the entirety of Zazie in the Metro as a family-type film, about a sensible little girl surrounded by foolish and incompetent grown-ups, although I am at a complete loss as to why one would desire such a reading.

Instead of a "children's movie" reading, I rather suspect that the presence of young Zazie in the center of this maelstrom of anarchy is a deliberate choice to direct the audience point-of-view such that the most extreme absurdities of the film are made less grotesque. We expect a story about a child to be more fantastic and dare I say zany than a story about adults, and Zazie in the Metro exploits that expectation, leading us to first laugh at the film and only realising the implications of what we're laughing at moments later. The film is constantly one step ahead of the audience, always just a little bit smarter than we are. That might be the most uncomfortable part of the whole experience. But then, nobody would ever argue that the revelation that we're all living like foolish cattle should be comfortable.

And for all that, I don't believe that I'm familiar with any New Wave film so full of that energy as Louis Malle's third feature, Zazie in the Metro. Part of that energy comes from the subject: the misadventures of a young girl set loose in Paris. And part of it comes from the film's rather unique status in the New Wave canon as being not just a comedic riff on a serious genre; in fact it is an outright comedy.

Here is the first thing that I learned about New Wave comedy: it is freakishly unhinged. In my life, I have been more than happy to call Truffaut's Shoot the Piano Player or Godard's A Woman is a Woman or Band of Outsiders "surreal" in the way that they break the rules of cinematic diegesis (that is, the realty of the narrative world, which is different from the reality of what is represented onscreen) beyond the basic experimentation that was a hallmark of the New Wave; but Zazie knocks them all away. It is not merely Surrealist, it leaves Surrealism behind on its merry trip into outright Absurdism, and while I watched the film I thought of neither Godard nor Truffaut, nor Buñuel, but Monty Python's Flying Circus and its aggressive abandonment of causality and even physics in the pursuit of the grotesque and ineffable.

Even that's not precisely right. The Pythons were largely content to embrace the moral and aesthetic anarchism of absurdity in the pursuit of humor, and while Zazie in the Metro has its fair share of slapstick and farce and potty jokes, much of the anarchism (even that same juvenile vaudeville) is considerably more dangerous than I am accustomed to. For example: reasonably early in the film, Zazie (Catherine Demongeot) find herself being pursued by a man of no permanent name (Vittorio Caprioli), who at this point seems to be a pedophile (nor is it ever demonstrated that he isn't a pedophile, but it falls into the background). He chases her through Paris in an extended setpiece that can only be called an homage to Tex Avery: not just in its manic speed, but in Zazie's ability to completely disregard physics, by being in multiple places at once, by being able to jump around in impossible ways, by being able to materialise cartoon bombs at will, and by the man's reaction to blowing up being to turn completely black except for his eyes and mustache. Set aside the fact that, moments before this scene began, Zazie was being menaced by a sex predator; the mere fact that a live-action film completely co-opts the vocabulary of a cartoon is shocking and somehow offensive to the mind, yet it is also deliriously funny.

"Delirium." Let us hold onto that word, savor it and consider it for the current subject. It refers to an anxious state of mind characterised by confusion and hallucination and incoherence, and all of these are perfectly correct adjectives to describe Zazie in the Metro.

Godard famously held that the aesthetics of a film should be a political argument, but he was never able to successfully demonstrate such a thing; late in the 1960s, he began grafting the vocabulary of the New Wave onto explicitly political screenplays, but there was no concomitant change in his style. Politics was always in his writing, not his directing. But even if he had succeeded in his quest, Malle would have already beaten him to the punch, for Zazie is a political argument to its very core. "Dangerous anarchy," I stated before, and I will repeat it: this is an anarchic film, not "anarchic" in the way that we playfully describe the Marx Brothers or screwball comedy or, yes, Monty Python; "anarchic" because it rips things apart and eliminates meaning, because it implicitly argues that the very idea of society is fascist. To be a human amongst humans is to live in a world of rules, and Zazie in the Metro proceeds to eliminate those rules not just in its plot, although it does so, but in its make-up. The cartoon homage is a good reference point for that, as animation in general and Tex Avery's chase films in particular have long been regarded as the ultimate in cinematic anarchy, where even the totalitarianism of physics is overthrown. That's not the only anarchy in the film, however, not by a long shot: there are constant, completely unmotivated continuity errors; the soundscape is violently loud and often unconnected to the imagery; characters refuse to act with any consistency or regard for the situations around them. Even the sets themselves refuse to be nailed down, as neatly demonstrated in a bar that is being constantly redecorated, including a phone that blows up in the middle of a conversation and continues to operate.

Of course, Godard was certainly no stranger to the idea that society is inherently fascist. It's just that the only way he knew to film that theme was to put heavy-handed dialogue in the mouth of a pop star wearing a Coca Cola shirt intercut with title cards that are bawdy anagrams of Proust quotes.* Not that I don't love Godard for that sort of thing, because of course I do and I always will, but he had to work for his politics. Malle's film embodies politics, seemingly without effort. It is the most political New Wave film I have ever seen, in fact, to such an unforgiving degree that it is somewhat uncomfortable to watch.

That the film is ameliorated whatsoever in this total discomfort, and returned to the realm of comedy, is because it is centered around an eleven-year-old girl. And if one were so inclined, it would be possible to read the entirety of Zazie in the Metro as a family-type film, about a sensible little girl surrounded by foolish and incompetent grown-ups, although I am at a complete loss as to why one would desire such a reading.

Instead of a "children's movie" reading, I rather suspect that the presence of young Zazie in the center of this maelstrom of anarchy is a deliberate choice to direct the audience point-of-view such that the most extreme absurdities of the film are made less grotesque. We expect a story about a child to be more fantastic and dare I say zany than a story about adults, and Zazie in the Metro exploits that expectation, leading us to first laugh at the film and only realising the implications of what we're laughing at moments later. The film is constantly one step ahead of the audience, always just a little bit smarter than we are. That might be the most uncomfortable part of the whole experience. But then, nobody would ever argue that the revelation that we're all living like foolish cattle should be comfortable.

Categories: comedies, french cinema, sunday classic movies