This is what happens to curious little boys

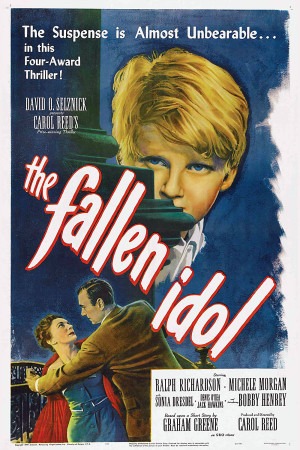

A year before creating their beloved The Third Man director Carol Reed and writer Graham Greene collaborated for the first time on an adaptation of Greene's short story "The Basement Room." The result was The Fallen Idol, a minor masterpiece that made quite a splash on its release before plunging into oblivion along with the great majority of the director's output.

I'll bet you all know my biases enough to know that this next bit doesn't start with "Thank God, because The Fallen Idol is a sheer drudge," but instead with "A shame, because..." And it's a shame because this film, out of all the many hundreds I have seen in my life, is the finest single example I can name of a child's point-of-view. How many films there have been that focus on a child, but view the world through a short, cynical adult; here is a film that's not even "about" a child so much as it is observed by a child, with all of the biases and confusions that come when a child tries to figure out what is going on in the world of grown ups.

Reed announces his attentions boldly, in one of the most unique and arresting first shots that I have ever seen in a motion picture. The moment the opening credits end, we start in on the close-up of a young boy looking down between the rails of a banister. In a few short minutes of exposition, we learn that this is Phillipe (Bobby Henrey), the son of the French ambassador to England; that his father is journeying to bring his mother home from a months-long stay in hospital; that his closest friends in the world are the embassy butler Baines (Ralph Richardson) and a snake named Macgregor.

But I'm not ready to leave that first shot yet. It introduces an image that will be used several times in the film: the camera looking at Phillipe looking at something else, with his face obscured by whatever he's hiding behind (the banister, a door, a tablecloth). This implies any number of things, chiefly voyeurism and (given that this is very much a post-war British film) espionage - voyeurism having the particular side-meaning of implicating Phillipe's viewpoint with the audience. Indeed, all of those instances of us watching Phillipe are immediately followed by a first-person shot of whatever he's looking at. In this way, The Fallen Idol is one of the first cinematic explorations of the voyeuristic act of watching a movie, beating Hitchcock's Rear Window to the punch by some six years.

As interesting as that is, it's garden-variety Gaze Theory stuff compared to the truly startling way that Reed and Graham co-opt the framework of a spy thriller. That's what The Fallen Idol is, basically: a spy thriller that, pivoting as it does on a child's point-of-view, is concerned with the smallest and grubbiest of secrets, and the most banal of mysteries. For Phillipe's voyeurism shortly leads him to witness Baines having tea with his lover, Julie (Michèle Morgan), thereupon to have the butler swear him to secrecy. All the rest of the tragedy of the story springs from this tiny domestic intrigue, and the boy's inability to grasp what's going on.

The disconnect between what Phillipe sees and what he understands isn't merely used to drive the plot; it's the chief thematic concern of the film. From the first shot to the last, we are constantly asked to identify with the boy, both through the mechanics of the plot and the skillful manipulation of the camera. This means that we are only given information as he processes it (with a handful of exceptions, mostly expository); yet because we are adults, theoretically, we understand what things mean in a way that our surrogate does not. I've already mentioned that the film makes us voyeurs like Phillipe, and perhaps this is the time to expand on that: there is a subtle and wholly successful parallel set up between our specific experience of watching The Fallen Idol and understanding what Phillip does not, and our general experience of watching contemporary cinema. Recall in the 1940s, censorship codes were still in full effect, and one couldn't go around saying "he's fucking the secretary!" Instead, filmmakers were forced to create subtle cues that would allow the audience to understand what was being implied. The Fallen Idol deconstructs this going and coming: on the one hand, by presenting the story of a love affair through the perspective of a naïve little boy, we are required to acknowledge that we understand things on a different level than he does, that we with our experience are more able to unpack meaning. From the other side, the film includes two scenes only partially shown from Phillipe's presence that typify, in an exaggerated way, the whole process of watching a Code-era film. The first concerns a hooker in a police department (a scene idiotically cut from the initial American release and only restored in late 2005), using all the normal tricks to make us realise she's a hooker; but when Phillipe enters the scene, the movie launches into a risqué series of one-liners that underlines how confusing these representational tropes must be to an innocent audience. In the second, Julie is asked about being "intimate" with Baines, but because she is not a native speaker of English, she does not understand this euphemism. It couldn't be any clearer: the film is asking us to recognise the whole host of agreements we make every time we watch a film, knowing that it tells tiny lies to make us understand the deeper meaning of what's going on.

Lies, tiny and not, are the other main concern of The Fallen Idol. Like I said, it's basically a story of espionage, and much like The Third Man, most of the intrigue revolves around one person getting in over his head in an effort to figure out what's going on with his close friend (Baines, the eponymous idol). But where The Third Man takes as its backdrop the chaos of Europe after the war, The Fallen Idol rarely moves outside the confines of the embassy. Which is as it should be, for all children are naturally solipsistic, and this is a tale informed by a child. Where this film and The Third Man part ways, of course, is that the latter film is about the slow and hurtful process of uncovering secrets, while Phillipe's story is mostly about the accretion of lies. While not malicious, the boy is selfish, and he has such a simple view of things: if I tell the truth, bad things will happen, and if I lie, good things will happen. Later on, he is given a different set of rules, precisely the opposite; the black joke in the film comes at the end, when the relationship between lying and consequences has been confused and stripped away, and ambiguity is brought into the world, and Phillipe's childhood is gone (the ending is "happier" than in the short story, but far less black-and-white morally, and hence, I think, more mature). In essence, this is a story of learning that "the truth" is something no-one much cares about either way, perhaps the hardest and nastiest thing to learn on the road to growing up.

I wouldn't be me if I didn't at least touch on the look of the film (beyond the brief mention of recurring POV shots earlier). It's a sad fact that The Fallen Idol lacks the mad, freewheeling style of the radical The Third Man, and that is quite enough for me to dismiss out of hand the many revisionists who would plead that we consider this this superior film; but it's still a fine thing to look at. Between Vincent Korda's sets and George Périnal's cinematography, the interior of the embassy is turned into a labyrinth as dark and secretive and dangerous as the bombed-out Vienna of Reed's following work, and there are even a few shots that prefigure the famous canted angles of The Third Man, mostly those which address the high ledge which will result in a death that splits the film in half and changes Phillipe's lies from harmless to truly damaging. This split also divides the film into a "light" and "dark" half, the latter 50 minutes using a fairly advanced (for a British film in 1948) palette of noir techniques, especially in this film's version of "Harry Lime in the sewers," Phillipe running through the wet streets of London at night.

In short, this film progresses in all ways - narratively and visually - from the benign to the dark and dangerous. This is, maybe, a pat and obvious way to set up a coming-of-age story. But this is a story in which adulthood isn't about maturity and responsibility, it's about secrets and lies and protecting oneself by misleading a child who isn't clever enough to realise that he's much more clever than he's given credit for. It is, in other words, a childhood story by one of the cinema's most literate & cynical writer-director teams, which is to say, one of the most British.

I'll bet you all know my biases enough to know that this next bit doesn't start with "Thank God, because The Fallen Idol is a sheer drudge," but instead with "A shame, because..." And it's a shame because this film, out of all the many hundreds I have seen in my life, is the finest single example I can name of a child's point-of-view. How many films there have been that focus on a child, but view the world through a short, cynical adult; here is a film that's not even "about" a child so much as it is observed by a child, with all of the biases and confusions that come when a child tries to figure out what is going on in the world of grown ups.

Reed announces his attentions boldly, in one of the most unique and arresting first shots that I have ever seen in a motion picture. The moment the opening credits end, we start in on the close-up of a young boy looking down between the rails of a banister. In a few short minutes of exposition, we learn that this is Phillipe (Bobby Henrey), the son of the French ambassador to England; that his father is journeying to bring his mother home from a months-long stay in hospital; that his closest friends in the world are the embassy butler Baines (Ralph Richardson) and a snake named Macgregor.

But I'm not ready to leave that first shot yet. It introduces an image that will be used several times in the film: the camera looking at Phillipe looking at something else, with his face obscured by whatever he's hiding behind (the banister, a door, a tablecloth). This implies any number of things, chiefly voyeurism and (given that this is very much a post-war British film) espionage - voyeurism having the particular side-meaning of implicating Phillipe's viewpoint with the audience. Indeed, all of those instances of us watching Phillipe are immediately followed by a first-person shot of whatever he's looking at. In this way, The Fallen Idol is one of the first cinematic explorations of the voyeuristic act of watching a movie, beating Hitchcock's Rear Window to the punch by some six years.

As interesting as that is, it's garden-variety Gaze Theory stuff compared to the truly startling way that Reed and Graham co-opt the framework of a spy thriller. That's what The Fallen Idol is, basically: a spy thriller that, pivoting as it does on a child's point-of-view, is concerned with the smallest and grubbiest of secrets, and the most banal of mysteries. For Phillipe's voyeurism shortly leads him to witness Baines having tea with his lover, Julie (Michèle Morgan), thereupon to have the butler swear him to secrecy. All the rest of the tragedy of the story springs from this tiny domestic intrigue, and the boy's inability to grasp what's going on.

The disconnect between what Phillipe sees and what he understands isn't merely used to drive the plot; it's the chief thematic concern of the film. From the first shot to the last, we are constantly asked to identify with the boy, both through the mechanics of the plot and the skillful manipulation of the camera. This means that we are only given information as he processes it (with a handful of exceptions, mostly expository); yet because we are adults, theoretically, we understand what things mean in a way that our surrogate does not. I've already mentioned that the film makes us voyeurs like Phillipe, and perhaps this is the time to expand on that: there is a subtle and wholly successful parallel set up between our specific experience of watching The Fallen Idol and understanding what Phillip does not, and our general experience of watching contemporary cinema. Recall in the 1940s, censorship codes were still in full effect, and one couldn't go around saying "he's fucking the secretary!" Instead, filmmakers were forced to create subtle cues that would allow the audience to understand what was being implied. The Fallen Idol deconstructs this going and coming: on the one hand, by presenting the story of a love affair through the perspective of a naïve little boy, we are required to acknowledge that we understand things on a different level than he does, that we with our experience are more able to unpack meaning. From the other side, the film includes two scenes only partially shown from Phillipe's presence that typify, in an exaggerated way, the whole process of watching a Code-era film. The first concerns a hooker in a police department (a scene idiotically cut from the initial American release and only restored in late 2005), using all the normal tricks to make us realise she's a hooker; but when Phillipe enters the scene, the movie launches into a risqué series of one-liners that underlines how confusing these representational tropes must be to an innocent audience. In the second, Julie is asked about being "intimate" with Baines, but because she is not a native speaker of English, she does not understand this euphemism. It couldn't be any clearer: the film is asking us to recognise the whole host of agreements we make every time we watch a film, knowing that it tells tiny lies to make us understand the deeper meaning of what's going on.

Lies, tiny and not, are the other main concern of The Fallen Idol. Like I said, it's basically a story of espionage, and much like The Third Man, most of the intrigue revolves around one person getting in over his head in an effort to figure out what's going on with his close friend (Baines, the eponymous idol). But where The Third Man takes as its backdrop the chaos of Europe after the war, The Fallen Idol rarely moves outside the confines of the embassy. Which is as it should be, for all children are naturally solipsistic, and this is a tale informed by a child. Where this film and The Third Man part ways, of course, is that the latter film is about the slow and hurtful process of uncovering secrets, while Phillipe's story is mostly about the accretion of lies. While not malicious, the boy is selfish, and he has such a simple view of things: if I tell the truth, bad things will happen, and if I lie, good things will happen. Later on, he is given a different set of rules, precisely the opposite; the black joke in the film comes at the end, when the relationship between lying and consequences has been confused and stripped away, and ambiguity is brought into the world, and Phillipe's childhood is gone (the ending is "happier" than in the short story, but far less black-and-white morally, and hence, I think, more mature). In essence, this is a story of learning that "the truth" is something no-one much cares about either way, perhaps the hardest and nastiest thing to learn on the road to growing up.

I wouldn't be me if I didn't at least touch on the look of the film (beyond the brief mention of recurring POV shots earlier). It's a sad fact that The Fallen Idol lacks the mad, freewheeling style of the radical The Third Man, and that is quite enough for me to dismiss out of hand the many revisionists who would plead that we consider this this superior film; but it's still a fine thing to look at. Between Vincent Korda's sets and George Périnal's cinematography, the interior of the embassy is turned into a labyrinth as dark and secretive and dangerous as the bombed-out Vienna of Reed's following work, and there are even a few shots that prefigure the famous canted angles of The Third Man, mostly those which address the high ledge which will result in a death that splits the film in half and changes Phillipe's lies from harmless to truly damaging. This split also divides the film into a "light" and "dark" half, the latter 50 minutes using a fairly advanced (for a British film in 1948) palette of noir techniques, especially in this film's version of "Harry Lime in the sewers," Phillipe running through the wet streets of London at night.

In short, this film progresses in all ways - narratively and visually - from the benign to the dark and dangerous. This is, maybe, a pat and obvious way to set up a coming-of-age story. But this is a story in which adulthood isn't about maturity and responsibility, it's about secrets and lies and protecting oneself by misleading a child who isn't clever enough to realise that he's much more clever than he's given credit for. It is, in other words, a childhood story by one of the cinema's most literate & cynical writer-director teams, which is to say, one of the most British.

Categories: british cinema, film noir, mysteries, sunday classic movies