Guns and ammo

I'm going to start off with the bold statement, and work my way back from there: Clint Eastwood is one of the greatest working American filmmakers.

This is not, mind you, the petulance of a Mystic River/Million Dollar Baby fanboy. To some degree, I've thought something like that since long before either of those two films were made, and I'm on record somewhere as claiming that Unforgiven is one of the ten best American films of the 1990s (a view that as it happens, I still hold).

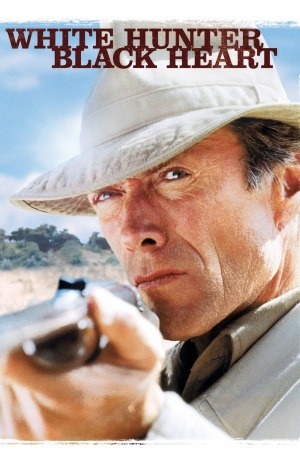

A full-scale defense of the cinema of Clint Eastwood is probably necessary, and who knows? Maybe I'll even write one some time. For the moment, I'm going to focus instead on just one of his films, all but forgotten these days, despite being one of the best and most challenging, and certainly most interesting films of his career: from 1990, White Hunter, Black Heart.

Hop in the Way-Back machine with me: in 1988, after 12 films that had stubbornly refused to net him any respect as a director (despite the fact that one of them, The Outlaw Josey Wales, was the best western since 1971, and one of them, Pale Rider, was the second-best western since 1971), Eastwood made Bird, a biopic of legendary jazz man Charlie Parker, and because it was not a scummy genre movie, all of a sudden people regarded him as a proper filmmaker. From there, it was a swift four years until Eastwood found himself accepting a Best Picture Oscar for one of the very few films that has ever deservingly won that award, Unforgiven.

Something happened in between those two films: he made a film that was something of a cross between them, a mostly true story about a sociopathic antihero. It was modestly-received, and never talked of again (it's not true, as is often said, that White Hunter, Black Heart was precisely in between Bird and Unforgiven; the eminently disposable comedy The Rookie was released later in 1990).

Before I dig into White Hunter, Black Heart in earnest, I must bring up another director of hyper-masculine genre films, who never had to fight for recognition quite like Eastwood did: John Huston. Huston is a man of legend: an iconoclast, a rebel, a womanizer (five marriages, all ending in divorce), one of the great drinkers of cinema history, a hunter, and all-round charming psychopath. His sets were notorious for their chaotic, alcohol-fueled energy, and it's probably unsurprising that he oversaw what is still regarded in hushed tones as one of the most infamous location shoots of all time: The African Queen, from 1951.

Endless stories surround that shoot, and I only have the time for one: James Agee was the writer credited with the screenplay, and he was brought to Africa to help shape the story as Huston filmed (at this stage in his career, the notion of a finished shooting script was anathema to the director). Both men, Agee and Huston, liked to live hard, and they fed off of each other in weeks of heavy drinking and smoking. And then Agee had a non-fatal heart attack, and was forced to return to the US. He was replaced by a friend of Huston's, Peter Viertel, who was amazed by the decadence of his director's lifestyle. Of particular fascination was Huston's fixation on hunting elephants, to the degree that making a movie was more of an inconvenience than anything else.

In 1953, Viertel translated his experience into the thinly-disguised novel White Hunter, Black Heart. And 37 years later, we arrive, finally, at the current subject.

There is really only one place to begin, and that is with Clint Eastwood himself. History is littered with actors directing themselves, or directors acting in their own pictures, and this tends not to reflect on much beyond vanity. There are, however, an extremely small number of films - The Rules of the Game, maybe Annie Hall, anything by Orson Welles, I'm sure a few others that don't immediately spring to mind - in which the presence of the director in the cast is itself a major component of the film's theme. And Eastwood usually just casts himself because he's available, in White Hunter, Black Heart, it's significant-unto-distractingly obvious that it matters that the director is the lead. After all, it's a film about a director.

There's an incredible density of layers here: 1) a filmmaker known for his adventure stories and regressive masculinity directs a story in which he presents another director known for his adventure stories and masculinity as a villain because of the traits the two men share; 2) a director known for the expediency and discipline of his shoots plays a director whose dictatorial, arbitrary whims come perilously close to wrecking his film; 3) a director stages a fictional director pushing people to hell and back, meaning that the actual director has to push people to hell and back (the "Herzog" element); 4) Clint Eastwood (an easily-parodied icon) plays John Huston (an easily-parodied icon) so loosely as to suggest parody.

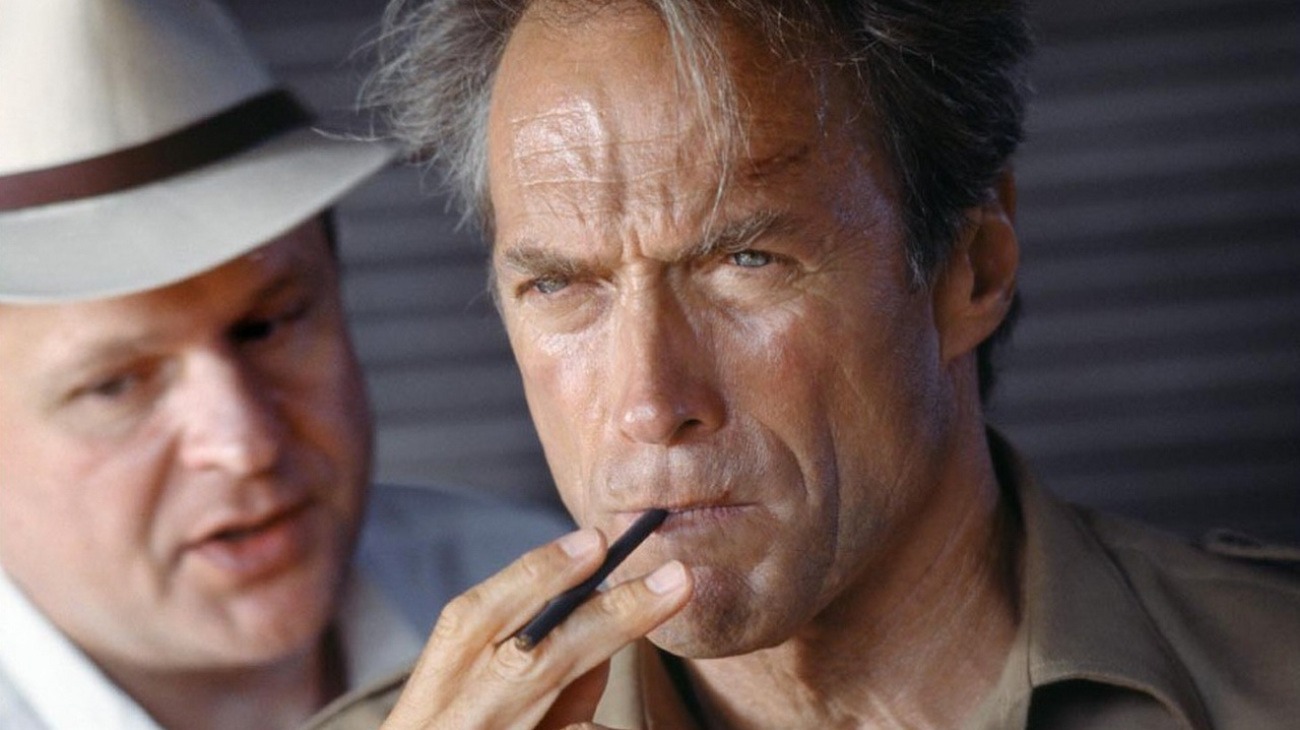

I think that last bit is the part that most people are going to notice first. Eastwood is known for playing one character: the quiet fighter with clenched teeth and a thin frown. There are significant variations within this type, but certainly nothing like watching him channel John Huston, a talkative man with a constant smile, wide eyes and that wonderful voice. It is the voice that stands out: to compensate, perhaps, for his natural mumbliness, the actor/director speaks in perfectly formed, clipped syllables, spoken in an arrhythmic lilt that almost feels like he learned his lines phonetically. What's scary is that there's no mistaking it for anything other than Huston. (Okay, I might as well come clean: Eastwood is playing "John Wilson." But the movie knows what it's about, and so do I).

I'm not sure that it's a "good" performance, but it is precisely the performance that the film requires, and that is what is chiefly important. The point is that Wilson is a vast creature, something more than human (there's a line to this effect early on, when Eastwood/Huston/Wilson mentions that there's no real difference between a filmmaker and God), which necessarily means that he is inhuman. It's not quite fair to say that he's a caricature of malehood; but he is a monstrous exaggeration of malehood.

Eastwood's films tend to fall into two camps: those which celebrate violent masculinity (e.g Dirty Harry) and those which repudiate it (e.g the pervasively-misread Outlaw Josey Wales; might I mention, it seems like Eastwood has by now made more films discounting his early fascist ones than he made fascist ones to begin with). White Hunter, Black Heart does not come down firmly on either side: we are constantly shown the negative effects of Wilson's actions, and yet the movie is precisely the sort of thing that he might have made himself: a morally-pointed adventure fable about a powerful man in the wild. At the end, there are two lines of dialogue, spoken by two different people, one of which seems to imply that Wilson has been right all along, and one that implies that he's never been right about anything. The truth, doubtlessly, is somewhere in between. The end result is a film that recognises the universality of greys, even implicitly in its title, and this is something that no other Eastwood film does to the same degree, although Million Dollar Baby comes extremely close.

So easy is it to get caught up in the beautifully shifting, conflicting morality of its subject, one can almost fail to realise how well-crafted the whole thing is. Even when his scripts are terrible - and this is common - Eastwood is a great craftsman (actual Tim Brayton quote from 2003: "There are only two shots in all of [Mystic River] when he doesn't make the best possible choice"); his films are extremely casual about how visually dense they are. Case in point: the final shot of White Hunter, Black Heart contains more thematic punch than the entire screenplay preceding it. Which is not a slam against the screenplay.

It helps a great deal that when Eastwood finds someone he works well with, he clings to that person. This was Eastwood's third film with cinematographer Jack Green (fifth, counting two vehicles Eastwood starred in without directing), and his ninth with editor Joel Cox (who has edited all but one of Eastwood's films since 1977, up to and including Letters from Iwo Jima). Such relationships are not uncommon, but for someone whose shoots are as low-key as Eastwood's, they are vital; particularly his relationship with Cox, who already had enough of a handle on the director's style to keep the pace of this film at a relentless pace throughout. Even if the film lacked any moral heft - and scholars are divided on that point - it would still be a treat to look at.

How does all of this prove that Clint Eastwood is a truly great filmmaker for the ages? It doesn't. But I do think that it's far too easy to call him a simple director, with bald reactionary leanings, and this film is a good example against that, with its complex metanarrative and sense of cinema history and its shifting morality. It is not, at any rate, the product of a hack filmmaker. Indeed, it's one of the key texts in the evolution of Eastwood's escape from the generic cage that kept him down in the opinion of so many critics, and haunts him in certain circles even today.

This is not, mind you, the petulance of a Mystic River/Million Dollar Baby fanboy. To some degree, I've thought something like that since long before either of those two films were made, and I'm on record somewhere as claiming that Unforgiven is one of the ten best American films of the 1990s (a view that as it happens, I still hold).

A full-scale defense of the cinema of Clint Eastwood is probably necessary, and who knows? Maybe I'll even write one some time. For the moment, I'm going to focus instead on just one of his films, all but forgotten these days, despite being one of the best and most challenging, and certainly most interesting films of his career: from 1990, White Hunter, Black Heart.

Hop in the Way-Back machine with me: in 1988, after 12 films that had stubbornly refused to net him any respect as a director (despite the fact that one of them, The Outlaw Josey Wales, was the best western since 1971, and one of them, Pale Rider, was the second-best western since 1971), Eastwood made Bird, a biopic of legendary jazz man Charlie Parker, and because it was not a scummy genre movie, all of a sudden people regarded him as a proper filmmaker. From there, it was a swift four years until Eastwood found himself accepting a Best Picture Oscar for one of the very few films that has ever deservingly won that award, Unforgiven.

Something happened in between those two films: he made a film that was something of a cross between them, a mostly true story about a sociopathic antihero. It was modestly-received, and never talked of again (it's not true, as is often said, that White Hunter, Black Heart was precisely in between Bird and Unforgiven; the eminently disposable comedy The Rookie was released later in 1990).

Before I dig into White Hunter, Black Heart in earnest, I must bring up another director of hyper-masculine genre films, who never had to fight for recognition quite like Eastwood did: John Huston. Huston is a man of legend: an iconoclast, a rebel, a womanizer (five marriages, all ending in divorce), one of the great drinkers of cinema history, a hunter, and all-round charming psychopath. His sets were notorious for their chaotic, alcohol-fueled energy, and it's probably unsurprising that he oversaw what is still regarded in hushed tones as one of the most infamous location shoots of all time: The African Queen, from 1951.

Endless stories surround that shoot, and I only have the time for one: James Agee was the writer credited with the screenplay, and he was brought to Africa to help shape the story as Huston filmed (at this stage in his career, the notion of a finished shooting script was anathema to the director). Both men, Agee and Huston, liked to live hard, and they fed off of each other in weeks of heavy drinking and smoking. And then Agee had a non-fatal heart attack, and was forced to return to the US. He was replaced by a friend of Huston's, Peter Viertel, who was amazed by the decadence of his director's lifestyle. Of particular fascination was Huston's fixation on hunting elephants, to the degree that making a movie was more of an inconvenience than anything else.

In 1953, Viertel translated his experience into the thinly-disguised novel White Hunter, Black Heart. And 37 years later, we arrive, finally, at the current subject.

There is really only one place to begin, and that is with Clint Eastwood himself. History is littered with actors directing themselves, or directors acting in their own pictures, and this tends not to reflect on much beyond vanity. There are, however, an extremely small number of films - The Rules of the Game, maybe Annie Hall, anything by Orson Welles, I'm sure a few others that don't immediately spring to mind - in which the presence of the director in the cast is itself a major component of the film's theme. And Eastwood usually just casts himself because he's available, in White Hunter, Black Heart, it's significant-unto-distractingly obvious that it matters that the director is the lead. After all, it's a film about a director.

There's an incredible density of layers here: 1) a filmmaker known for his adventure stories and regressive masculinity directs a story in which he presents another director known for his adventure stories and masculinity as a villain because of the traits the two men share; 2) a director known for the expediency and discipline of his shoots plays a director whose dictatorial, arbitrary whims come perilously close to wrecking his film; 3) a director stages a fictional director pushing people to hell and back, meaning that the actual director has to push people to hell and back (the "Herzog" element); 4) Clint Eastwood (an easily-parodied icon) plays John Huston (an easily-parodied icon) so loosely as to suggest parody.

I think that last bit is the part that most people are going to notice first. Eastwood is known for playing one character: the quiet fighter with clenched teeth and a thin frown. There are significant variations within this type, but certainly nothing like watching him channel John Huston, a talkative man with a constant smile, wide eyes and that wonderful voice. It is the voice that stands out: to compensate, perhaps, for his natural mumbliness, the actor/director speaks in perfectly formed, clipped syllables, spoken in an arrhythmic lilt that almost feels like he learned his lines phonetically. What's scary is that there's no mistaking it for anything other than Huston. (Okay, I might as well come clean: Eastwood is playing "John Wilson." But the movie knows what it's about, and so do I).

I'm not sure that it's a "good" performance, but it is precisely the performance that the film requires, and that is what is chiefly important. The point is that Wilson is a vast creature, something more than human (there's a line to this effect early on, when Eastwood/Huston/Wilson mentions that there's no real difference between a filmmaker and God), which necessarily means that he is inhuman. It's not quite fair to say that he's a caricature of malehood; but he is a monstrous exaggeration of malehood.

Eastwood's films tend to fall into two camps: those which celebrate violent masculinity (e.g Dirty Harry) and those which repudiate it (e.g the pervasively-misread Outlaw Josey Wales; might I mention, it seems like Eastwood has by now made more films discounting his early fascist ones than he made fascist ones to begin with). White Hunter, Black Heart does not come down firmly on either side: we are constantly shown the negative effects of Wilson's actions, and yet the movie is precisely the sort of thing that he might have made himself: a morally-pointed adventure fable about a powerful man in the wild. At the end, there are two lines of dialogue, spoken by two different people, one of which seems to imply that Wilson has been right all along, and one that implies that he's never been right about anything. The truth, doubtlessly, is somewhere in between. The end result is a film that recognises the universality of greys, even implicitly in its title, and this is something that no other Eastwood film does to the same degree, although Million Dollar Baby comes extremely close.

So easy is it to get caught up in the beautifully shifting, conflicting morality of its subject, one can almost fail to realise how well-crafted the whole thing is. Even when his scripts are terrible - and this is common - Eastwood is a great craftsman (actual Tim Brayton quote from 2003: "There are only two shots in all of [Mystic River] when he doesn't make the best possible choice"); his films are extremely casual about how visually dense they are. Case in point: the final shot of White Hunter, Black Heart contains more thematic punch than the entire screenplay preceding it. Which is not a slam against the screenplay.

It helps a great deal that when Eastwood finds someone he works well with, he clings to that person. This was Eastwood's third film with cinematographer Jack Green (fifth, counting two vehicles Eastwood starred in without directing), and his ninth with editor Joel Cox (who has edited all but one of Eastwood's films since 1977, up to and including Letters from Iwo Jima). Such relationships are not uncommon, but for someone whose shoots are as low-key as Eastwood's, they are vital; particularly his relationship with Cox, who already had enough of a handle on the director's style to keep the pace of this film at a relentless pace throughout. Even if the film lacked any moral heft - and scholars are divided on that point - it would still be a treat to look at.

How does all of this prove that Clint Eastwood is a truly great filmmaker for the ages? It doesn't. But I do think that it's far too easy to call him a simple director, with bald reactionary leanings, and this film is a good example against that, with its complex metanarrative and sense of cinema history and its shifting morality. It is not, at any rate, the product of a hack filmmaker. Indeed, it's one of the key texts in the evolution of Eastwood's escape from the generic cage that kept him down in the opinion of so many critics, and haunts him in certain circles even today.